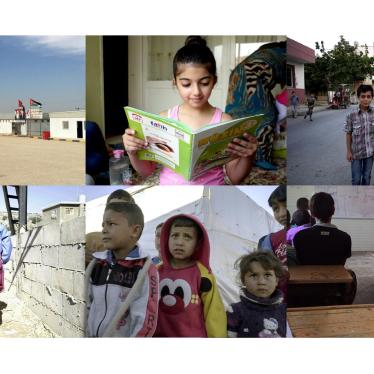

"The kids' education has gone backward ... We left our country and our homes and now they don't even have an education or a future," said Jawaher, a 24-year-old Syrian refugee living in Lebanon whose last name was withheld to maintain confidentiality.

Jawaher is just one of 1.1 million Syrian refugees living in Lebanon. The number of refugees there is alarming considering the country has a population of only around 4.5 million citizens — the largest number of refugees per capita in the world.

What's more, around half of those Syrian refugees are of school-age. A quarter million of them are out of school, with some never even having set foot in a classroom.

These children should not have to sacrifice their education to seek safety from the horrors of war in Syria.

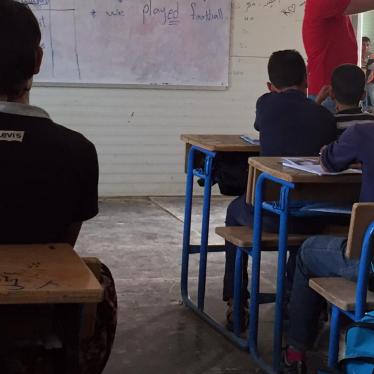

With financial support from international donors, Lebanon is making a considerable effort. It has waived school fees and allowed Syrian children to enroll in its public school system, which struggled even before the crisis.

But, despite these initiatives, Lebanon and the international community's failure to enroll hundreds of thousands of children in school will have serious implications for the lives of these children and the future of Syria.

Although Lebanon opened 200,000 public school spots for Syrians last year, only 158,000 non-Lebanese students enrolled. Of those aged 15 to 18, less than 3% were in public secondary schools.

A new Human Rights Watch report published in July identifies the barriers keeping children out of school. They include arbitrary enrollment requirements, a harsh residency policy that makes it difficult for refugees to maintain legal status, and transportation costs that impoverished families can't afford. The need for additional income also encourages prioritizing child labor over receiving an education.

The report is based on HRW's interviews with more than 150 refugee families. These are three stories of children who face some of the most prominent obstacles to education.

Barriers to enrollment

"This year, they really made it difficult for me," said Kawthar, a 33-year-old mother who fled to Lebanon in 2013.

Since she arrived, she's struggled to enroll her children in school because of inconsistencies in enrollment requirements. One school demanded several documents that Lebanon doesn't officially require, including vaccination records she left behind when fleeing Syria. Another school said her 15-year-old daughter, Mona, would need to take off her headscarf to attend.

Kawthar was eventually able to enroll her children in school, but said "they didn't learn anything" there; three months into the school year, they still hadn't received textbooks. Her son Wa'el has a learning disability, and sitting in the front row would help with his concentration, but the school would not permit this.

"It's a small request," Kawthar said. She eventually decided to pull them out because she couldn't afford to keep paying for their transportation.

Widespread child labor

Brothers Yousef, 11, and Nizar, 10, live across the street from a school, but have never set foot in a Lebanese classroom. Their parents cannot work, so for the past three years, they've sold gum on the street to help their family pay for rent and food.

It's dangerous work — the brothers have been beaten up, robbed, and arrested. But when we asked Yousef if he would like to enroll in school, he replied, "How could we afford it?"

Even when spaces are available, many refugee families can't afford to keep their children in school.

Lebanese residency policies make it very difficult for refugees to maintain legal status: They require an annual payment of $200 from every Syrian 15 or older and, for those not registered with the United Nations' refugee agency, sponsorship by a Lebanese national to legally stay in the country.

These stipulations, many of which are impossible for refugees living in poverty to meet, push them further underground, leaving them unable to move or work for fear of arrest.

Some families, therefore, rely on child labor to survive, because young children are rarely stopped at checkpoints, and can move around and work more freely.

Seventy percent of refugees now live below the poverty line, and some families said that school bus fees as low as $13 per month were the only barrier keeping their children out of school.

Determined to learn

"I used to go to school and school meant so much to me," she recalled.

Living in an informal camp in Lebanon, Bara'a wasn't able to enroll in school, initially.

In the same vein as Malala — who was shot in the head by the Taliban when she was 15 years old for promoting girls' education in Pakistan — Bara'a propped up a blackboard against a tree. She started teaching the younger children in her camp what she remembered from first grade in Syria.

"They should be studying so when they grow up they can be whatever they want," she said. "If one of them wants to be a teacher or a doctor she needs to know how to read and write."

Last fall, Bara'a finally enrolled in a public school, in an evening shift for Syrian students. But she isn't done teaching.

"I also help my friends and explain lessons to them," Bara'a said