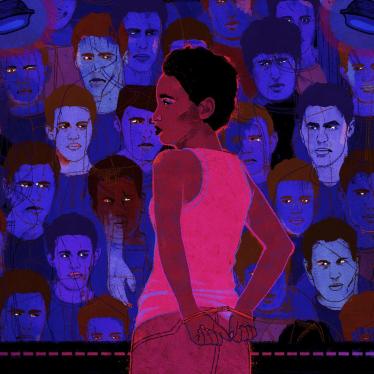

(Abuja) – Many survivors of sex and labor trafficking struggle with unaddressed health challenges, poverty, and abhorrent conditions upon their return to Nigeria. Nigerian authorities have failed to provide the assistance that survivors need to rebuild their lives and have unlawfully detained many of the already traumatized women and girls in shelters.

The 90-page report, “‘You Pray for Death’: Trafficking of Women and Girls in Nigeria,” provides detailed accounts of how human trafficking operates in Nigeria. Human Rights Watch found that the nightmare does not end for survivors who manage to return home. The Nigerian government should take steps to address the serious health conditions, social exclusion, and poverty faced by survivors, and stop further traumatizing survivors by detaining them in shelters.

“Women and girls trafficked in and outside Nigeria have suffered unspeakable abuses at the hands of traffickers, but have received inadequate medical, counseling, and financial support to reintegrate into society,” said Agnes Odhiambo, senior women’s rights researcher at Human Rights Watch. “We were shocked to find traumatized survivors locked behind gates, unable to communicate with their families, for months on end, in government-run facilities.”

Human Rights Watch interviewed 76 trafficking survivors in Nigeria, as well as government officials, civil society leaders, and representatives of donor governments and institutions providing support to anti-trafficking efforts in Nigeria.

The frequent trafficking of Nigerian women and girls to Europe and Libya has led to international headlines in recent years and to action by the Nigerian government. Many women and girls are also held in slavery-like conditions inside Nigeria.

Nigerian authorities have taken some important steps to address the country’s widespread problem of trafficking, including establishing shelters, assisting with medical care, and creating skills training and economic support programs for trafficking survivors.

However, the authorities rely too heavily on shelters, as opposed to community-based services, as the primary means of providing services to survivors. Nigerian authorities have also detained trafficking survivors in shelters, not allowing them to leave at will, often for many months, in violation of Nigeria’s international legal obligations. Protection should not be an excuse to arbitrarily detain women and girls and deprive them of their liberty and freedom of movement, Human Rights Watch said. Such detention conditions risk their recovery and well-being.

“I have been here for almost six months…. I eat and sleep and shout. They do not open the gate…” said an 18-year-old woman at a National Agency for the Prohibition of Trafficking in Persons (NAPTIP) shelter. “I told NAPTIP I do not want to stay here; I want to go home. They said they will allow me to go. I do not feel okay being here. I cannot stay here doing nothing.”

The journey into being trafficked is harrowing, and relief is hard to come by. Human Rights Watch documented how traffickers, most known to their victims, deceive women and girls, transport them within and across national borders, and then exploit them in various forms of forced labor.

Women and girls often believed they were migrating for high-paying overseas employment as domestic workers, hairdressers, or hotel staff. They were shocked to learn they had been tricked and were trapped in exploitative situations, with high “debts” to pay. They said their captors subjected them to forced prostitution and forced domestic work for long hours with no time to rest, and without pay. Traffickers made them have sex with men without condoms, and often compelled them to undergo abortions in unsanitary conditions, without pain medication or antibiotics.

Survivors described horrifying experiences leading to long-term trauma. Another woman said she was 18 when she was trafficked into forced prostitution in Libya and held for about three years. While in Libya, she was abducted by people she said were the Islamic State (also known as ISIS). She witnessed executions and bombings, and was sold from one trafficker to another. She became pregnant but lost her newborn baby during a bombing. She described her life after trafficking: “Sometimes I don’t want to see people. Sometimes I feel like I am going to kill myself. I don’t sleep well.”

Some women and girls said they suffered long-term mental and physical health problems and social stigma upon returning to Nigeria, where they struggled to get support and services. Many women and girls said they lacked money to support themselves and their families. Survivors described feeling deeply stressed and desperate.

Survivors said service providers generally did not actively involve them in decisions about their own assistance, and that service providers gave them insufficient information about services. Some reported long waiting periods without assistance after they contacted service providers to ask for help.

Outside of the government’s use of shelters, a network of nongovernmental organizations provides services to trafficking victims, including shelter accommodation, identification and family tracing, as well as rehabilitation and reintegration. However, representatives of some of these groups said they are poorly funded and are unable to meet survivors’ multiple needs for long-term comprehensive assistance.

Rehabilitation and reintegration efforts in Nigeria are also plagued by an over-emphasis on short-term skills training that also reinforces traditional gender roles, weak government efforts to identify victims, problems with funding and coordination, and poor oversight.

Nigerian authorities, including NAPTIP officials, should work urgently to improve assistance and services for internally identified and repatriated human trafficking survivors, including by ending the practice of denying freedom of movement to survivors housed in shelters. The Nigerian authorities should ensure that shelter policies and practices respect survivors’ human rights, ensure that no one is detained in shelters, and assess the impact of its “closed” shelter approach.

“Nigerian authorities are struggling with a crisis of trafficking, and working under challenging circumstances, but they can do a better job by listening to what survivors have to say about their own needs,” Odhiambo said. “To end trafficking and break cycles of exploitation and suffering, survivors need the government to help them heal from the trauma of trafficking and earn a decent living in Nigeria.”

Selected accounts from the report

Harrowing journeys and captivity

Juliana P., 23, was trafficked to Libya in 2015. She said she was stuck at sea and later held captive in Libya:

We stayed in the sea for five days. The food got finished. We did not know where we were. A man died and was pushed into the sea. People were crying, saying they did not know they would suffer this much. We met a group of Arabs; they took us in their boat and took us to prison. We stayed for six months. In prison the food they gave us was bread and chai and spaghetti with water. The water was very salty; it used to peel the skin. We were crying and they would beat us.

Trafficked into sexual slavery, forced prostitution, and forced labor

Joy P. described being trafficked at age 12 in 2017 from her home in Anambra State to Lagos State by a woman who deceived her, saying she would help with her education while she took care of the woman’s children. The woman forced Joy to clean and cook for two months without pay, then she took Joy to a brothel for forced prostitution:

One day she … took me to a hotel. I found one of the girls I met in Anambra there. She went to the owner of the hotel and said, “I have brought another girl.” The man said I was too young to stay there. She took me back to the house and bought drugs for me to make me fatter. After three weeks, she took me back but [he] did not accept me. She took me to another hotel and the owner accepted me. I told her, “This is not what you brought me here for.” She said I have to pay the money she used to bring me to Lagos before I can go back.

She brought condoms and gave me and said men will be coming to me. She gave me a room. Different men would come and sleep with me. I lost count of how many. I ran away after two days. My madam sent people to look for me. They found me and took me back to her house. She beat me and said that I had to pay her. She brought me something to drink to make me promise that I will not run away again. She took me back to the first hotel and he accepted me. It was painful. I was crying all the time.

Uma K., 32, said she was trafficked to Libya in 2013 by a man who lived on her street in Benin City. She said a madam held her and other girls in debt bondage and sexually exploited them. The madam forced Uma to undergo multiple abortions, charged her for the abortions, and forced her to work almost immediately after abortions:

I got sick, she said, “You are a nurse, you can treat yourself.” The woman used to beat me. You eat once a day. You wake up at 4 a.m. She beats you to wake you up, her and her husband. Men sleep with us without condoms. I got pregnant four times. She would do abortions for us… If she pays the nurse 40 Dinar; she charges you double. Immediately after that day, you will work.

Georgina K., 13, is from Benin, and said she had been in Nigeria for four years when Human Rights Watch interviewed her in 2017. She said her mother did not have money to enroll her in school, and her aunt offered to help:

She brought me here [Nigeria] to work to get money for vocational training. She took me to someone who sells food. I was hawking amala [Nigerian food made with cassava or yam flour]. They did not feed me. I ate nothing in the morning; they said I will eat when I return at around 3 p.m. I also did housework. She beat me and abused me verbally. She said I did not work well. I was always working. They paid my aunt, who said she will send the money to my parents. I am not sure she sent the money. I was sick, and they did not treat me.

Life in Nigeria after trafficking

Uma K. described life in Nigeria after she escaped from sexual exploitation in Libya:

Sometimes my friends mock me. A colleague [fellow nurse] of mine mocked me on Facebook saying I went to do prostitution in Libya…. Sometimes I cry. I think some of my family members are ashamed of me because when we are with people, they do not want to talk to me. Sometimes I feel as if people are mocking me even when I am just walking around. I haven’t sought counseling because I am ashamed; I don’t know what I will meet. Some people might mock you and not help you.

Joan A., 13, said she sometimes cannot afford food:

I live alone; my aunt gave me the house where I stay … she buys the food. Sometimes the church gives me food. Sometimes I don’t have food.

Adaku G., 31, was told by a neighbor that he could help her find work in France, but after a long harrowing journey through the Sahara Desert, she was trapped in Libya where a madam forced her into prostitution. She has suffered lingering health problems resulting from her ordeal:

My health is not good. I am always sick…. I have one thing after another. My family paid for the treatment…. I have pain in my lower abdomen, back, [and] I cannot bend. My waist pains.

Detention in shelters

Ebunoluwa E., 18, a trafficking survivor in a NAPTIP shelter said:

Since I have been here, I chop [eat] sleep, chop sleep. A pastor comes every Sunday to preach to us. We do daily prayer and devotion. I have not been doing any vocational training. They have not asked me what I want to do. Yesterday was three weeks here. I have not spoken to my mum. I went to the manager and said I want to speak to my mum to tell her I am here, she asked why I did not tell the JDPC [Justice Development and Peace Caritas Commission], [an] NGO that came to interview us. NAPTIP has my phone. I do not have my passport. I saw it with JDPC. I am so sad, I want to go home. I do not like this place; too many rules. We are forced to wake up with a bell to pray. I have not been told when I will go home…. I have been crying since morning.

Gladness K., 24, said she was kept in a NAPTIP shelter for about three weeks and moved to another for a week without information about when she would go home:

I want to go to my mum… In Lagos they said I should be happy to come back because many people suffer and are exploited. They asked if I want to learn work, and I said I wanted to go home. They have not told me when I am going home; I called my mum this afternoon and I am not sure when she is coming to pick me.