The World Health Organization (WHO), the United Nations agency charged with guiding the global response to the coronavirus pandemic, has become a battleground for two sparring superpowers. On April 14, 2020, President Trump announced that he would halt U.S. funding for the organization pending a review into what he called the WHO’s “role in severely mismanaging and covering up the spread of the coronavirus.”

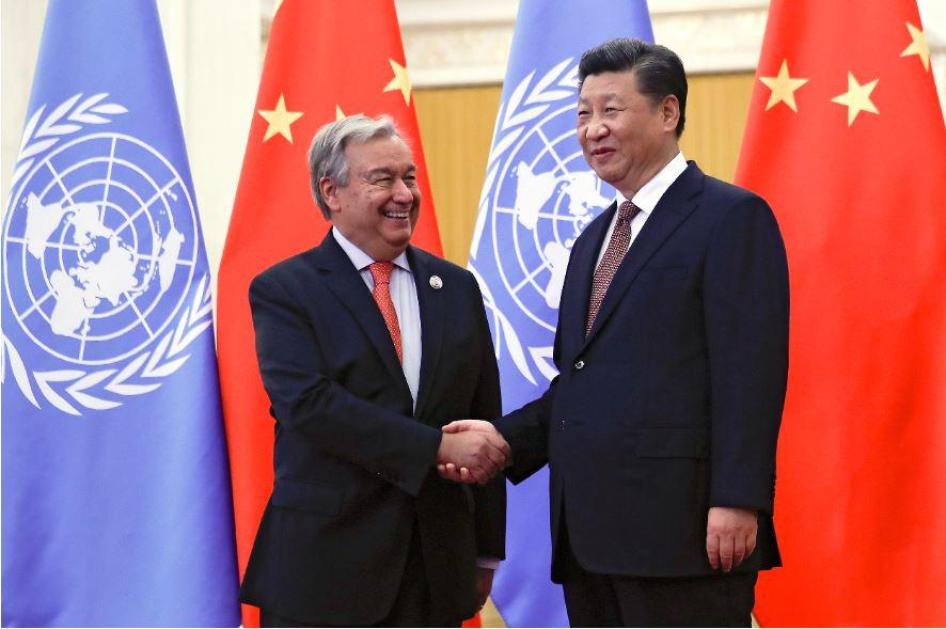

Within a week, China’s government offered $30 million as part of what it described as an effort to “[defend] the ideals and principle of multilateralism.” Earlier in April, China had secured a spot on a panel that advises the United Nations Human Rights Council on personnel appointments. (The Trump Administration pulled the U.S. out of the Council in 2018.) Nearly a third of the 15 specialized U.N. agencies are now led by Chinese appointees.

China has long sought to exert greater influence on global norms and rules across a whole range of issues, from trade, intellectual property, and Internet governance to environmental and labor standards and the definition of human rights, among others. Sometimes China’s officials work within established multilateral organizations and at other times they have created their own alternative China-led entities.

How is the Trump administration’s contempt for, and retreat from, multilateral bodies affecting China’s position and weight within them—or indeed its overall strategy for relations with these organizations? Do China’s leaders aspire to supplant the U.S. in steering these organizations? Or do they merely hope to make them more accommodating of the Chinese leadership’s interests and goals? If China does hold more sway in multilateral organizations, what does that portend for global governance more broadly? —The ChinaFile Editors

---

In the abstract, it is good for the Chinese and other governments to participate in the United Nations human rights system. And it would be truly extraordinary if Beijing were to invest its considerable resources and clout in using that system for positive change.

Imagine, for example, if the Chinese government ratified and observed the optional protocols to the human rights treaties that allowed people from China to bring individual complaints against the government to U.N. bodies. Imagine Beijing encouraging independent nongovernmental organizations from China to participate in U.N. reviews of the government’s human rights record, as many democracies around the world do.

Or, in perhaps the ultimate test of a government’s commitment to this multilateral organization, allowing U.N. experts and the U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights access to Xinjiang to investigate the alleged arbitrary detention of one million Turkic Muslims and other serious human rights violations.

Unfortunately, the Chinese authorities have demonstrated their agenda for these human rights bodies: to neutralize their ability to challenge China, to foster praise for Beijing, and to use them as a platform for rewriting key international norms.

The recent controversy around whether Chinese authorities reported the outbreak of COVID-19 promptly to another U.N. body, the World Health Organization (WHO), or whether the WHO was sufficiently aggressive in pushing China to share information, is just the latest example of Beijing’s departing from recognized protocols. In 2017, Human Rights Watch published a report detailing China’s concerted efforts to undermine a variety of U.N. human rights mechanisms, ranging from limiting access to U.N. forums for independent civil society groups—including groups doing no work on China—to Chinese diplomats threatening U.N. human rights experts.

These problems have only worsened in recent years as China has become more aggressive in international affairs and strengthened its diplomatic presence across the U.N. human rights system. It sent a letter to U.N. diplomats threatening consequences if they attended an event on rights abuses in Xinjiang, and has blocked members of the World Uyghur Congress from U.N. events.

Its latest priorities include advancing a resolution on what it calls “mutually beneficial cooperation” at the U.N. Human Rights Council. This is actually an effort to erode the Council’s mandate by elevating “cooperation” over holding countries accountable when they commit gross rights violations. Recently, the U.N. announced a partnership agreement with Tencent—a Chinese company that owns social media app WeChat, which is known to censor posts inside and outside China—only to suspend the partnership after governments and rights advocates protested. And on May 1, Chinese authorities rejected WHO participation in investigating the origins of the pandemic.

China’s influence at the U.N. and other multilateral institutions will most likely continue to grow. The challenge is whether sufficient numbers of rights-respecting governments will hold the world’s second-biggest economy and permanent member of the U.N. Security Council accountable for serious human rights violations and strengthen key international institutions. The risks have never been clearer. Governments need to stand up to Beijing, speak out, and resist those efforts to distort the international framework.