Summary

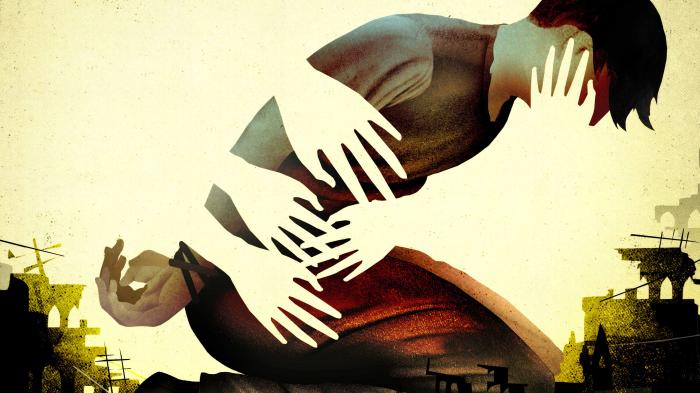

I would like you to pass on our voice. It’s not a voice. It’s a cry of pain. We have been here in Lebanon because they not only raped us, they also raped our land and dignity.

—Male survivor of conflict-related sexual violence in Syria, February 2019

Since the Syrian conflict began in March 2011, men and boys and transgender women have been subjected to rape and other forms of sexual violence by the Syrian government and non-state armed groups, including the extremist armed group Islamic State (also known as ISIS). Heterosexual men and boys are vulnerable to sexual violence in Syria, but men who are gay or bisexual—or perceived to be—and transgender women are particularly at risk.

While women and girls are disproportionately targeted by conflict-related sexual violence (CRSV), men and boys are also impacted. However, existing services within gender-based violence (GBV) and child protection are focused almost exclusively on responding to the needs of women and girls and very little attention is paid to the needs of men and boys. Limited data and underreporting—in part fueled by stigma around male vulnerability and reluctance to talk about experiences of sexual violence or seek help for its long-term physical and psychological impact—have contributed to male survivors not receiving adequate attention and help.

This report is based on interviews Human Rights Watch conducted in Lebanon with 40 gay and bisexual men and transgender women—some of whom were perceived by perpetrators to be gay men—and non-binary individuals, as well as 4 heterosexual men. The survivors all described their experience of sexual violence in Syria. We also conducted interviews with 20 caseworkers and representatives of humanitarian organizations operating in Lebanon. While many of the men and boys and transgender women interviewed have also experienced sexual violence in Lebanon, those incidents lie outside the purview of this report.

The report finds that men and boys, regardless of their sexual orientation or gender identity, are vulnerable to sexual violence in the context of the Syrian conflict. According to interviewees, gay and bisexual men and transgender women are subject to increased and intensified violence based on actual or perceived sexual orientation or gender identity. The sexual violence described included rape, sexual harassment, genital violence (beating, electric shock and burning of genitals), threat of rape of themselves or female family members, and forced nudity by state and non-state armed groups. This violence has taken place in various settings, including Syrian detention centers, checkpoints, central prisons, and within the ranks of the Syrian army.

This report also finds that survivors of sexual violence may suffer from various psychological traumas such as depression, post-traumatic stress, sexual trauma, loss of hope and paranoid thoughts. Due to the sexual violence they have been subjected to, survivors may also suffer from physical traumas, including severe pain in their rectum and genitals, rectal bleeding, and muscle pain, and may have sexually transmitted infections (STIs), including HIV.

Men and boys, transgender women, and non-binary survivors of sexual violence told Human Rights Watch that they did not seek any medical or mental health services in Syria for a range of reasons, including shame, fear of stigma, and a lack of trust in the health care system. Syrian survivors of sexual violence who fled to Lebanon told Human Rights Watch they found limited services and inadequate support from humanitarian organizations. This is often due to lack of funding and personnel trained to respond to their specific needs. For example, there are no protection facilities in Lebanon, such as safe shelters, for men or trans women.

In 2013, the United Nations (UN) Security Council for the first time stated in Security Council Resolution 2106 that conflict-related sexual violence also affects men and boys. The United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR) and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), including All Survivors Project, the Women’s Refugee Commission, Lawyers & Doctors for Human Rights and the Refugee Law Project, have provided significant documentation on the nature and extent of sexual violence perpetrated against men and boys in Syria and elsewhere, and the specific needs of male survivors. This has helped to address the dearth of research.

In March 2018, the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic (the Syria COI) published a report with detailed evidence on sexual violence against men and boys in Syria. On April 23, 2019, the UN Security Council adopted resolution 2467 on conflict-related sexual violence, which recognizes that men and boys are also targets of sexual violence in both conflict and post-conflict settings. Resolution 2467 acknowledges the need for enhanced medical and mental health support for survivors of sexual violence and calls on UN member countries to ensure that survivors of sexual violence receive nondiscriminatory access to medical and psychosocial care based on their needs.

The explicit recognition and documentation of CRSV against men and boys as sexual violence is an important step to ensure provision of services tailored to the needs of all survivors of sexual violence. This moves the issue out from being considered only under the more general rubric of “torture,” under which it has previously fallen in reporting and legal analysis. This report aims to shed light on the sexual nature of crimes perpetrated against Syrian men and boys and transgender women.

In a context of shame, stigma, and silence surrounding sexual violence against men and boys—whatever their sexual orientation—and also for transgender women and non-binary people, acknowledging such violence is a prerequisite to providing adequate services and care. It is also vital in challenging the social and cultural assumptions that men are invulnerable, which often underpins the stigma experienced by male and transgender survivors. Increased research on the topic, and attention to the plight of male survivors at the UN Security Council, adds to the momentum toward more adequate service provision.

International donors, including the European Union, should urgently provide resources for tailored medical, psychological and social support programs in Lebanon for men and boys, trans women, and non-binary survivors of sexual violence, without diverting funding from services for women and girls, which is already very scarce. Without funding, humanitarian organizations and service providers in Lebanon cannot meet the needs of the full range of CRSV survivors. Service providers and humanitarian organizations in Lebanon should provide comprehensive and confidential medical and mental health services to male, transgender, and non-binary survivors of sexual violence, with staff trained to handle their needs effectively and appropriately.

Recommendations

To the United Nations Security Council

- Ensure full implementation of Resolution 1325 and subsequent resolutions on conflict-related violence, especially Resolution 2467. This includes strengthening policies that offer appropriate responses to male survivors, challenging cultural assumptions about male vulnerability to such violence, and focusing more consistently on the gender specific nature of sexual violence in conflict and post-conflict situations while monitoring, analyzing and reporting such violence and providing non-discriminatory access to medical and psychosocial services to survivors of sexual violence.

To the International, Impartial and Independent Mechanism

- Ensure that further evidence and information is collected on conflict-related sexual violence against men and boys, transgender women, and non-binary people in Syria.

To Humanitarian Organizations and Service Providers in Lebanon

- Provide comprehensive and confidential mental health and psychosocial support to female and male survivors of sexual violence, especially addressing long-term effects.

- Provide targeted medical services to male and gay, bisexual, and transgender (GBT) survivors of sexual violence, in addition to the targeted services for women and girls. These services should include voluntary and confidential testing for HIV and appropriate counseling, and prophylaxis and presumptive treatment for those infected with HIV/AIDS; testing and treatment for other sexually transmitted infections; and care for any injuries incurred.

- Conduct evidence-based needs assessments and research to identify specific needs of survivors of sexual violence in order to design gender-competent programming and services.

- Integrate responses for male survivors (adult and child) and GBT survivors into sexual violence-related referral pathways and ensure robust referral pathways for all survivors.

- Train all relevant staff including case managers, social workers and front-line medical workers on clinical management of rape for both female and male survivors, as well as the specific needs of male survivors and GBT survivors.

- Hire staff with expertise in human rights, protection, and care for LGBT survivors and train all staff to assist LGBT survivors.

- Gather data on patterns of sexual violence against men and boys, with a view to assessing the scope of sexual violence committed against men and boys and establishing prevalence of sexual violence against men and boys in the Syrian conflict.

- Raise awareness about male sexual violence in the refugee and host communities to contribute to the reduction of stigma, remove the barriers to reporting of male survivors, and build knowledge about how and why male survivors of sexual violence should seek services.

- Create safe shelters for male survivors and GBT survivors of sexual violence.

To the Lebanese Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Interior

- Ensure that health care workers and police are trained to work with traumatized victims and witnesses, including in clinical management of rape of male survivors and identification of male survivors of sexual violence.

To the Syrian Government

- Release all arbitrarily detained persons, in line with Syria’s commitment under point 4 of the Anan plan, “including especially vulnerable categories of persons, and persons involved in peaceful political activities.”[4]

- Immediately halt the practice of enforced disappearance, arbitrary arrest and detention, and the use of torture and sexual violence in detention facilities.

- Conduct prompt, thorough, and objective investigations into allegations of arbitrary detention, use of torture, enforced disappearances, and deaths in custody, and bring the perpetrators to justice.

- Suspend or hold accountable security forces, government forces and shabiha (pro-government militia) against whom there are credible allegations of committing acts of sexual violence.

- Ensure that survivors have information about relevant health and psychosocial services, including that they should be accessed on an urgent basis, as well as facilitate victims’ access to them through safe and confidential mechanisms.

- Repeal Article 520 of the Syrian Penal Code 1949, which criminalizes “any unnatural sexual intercourse.”

To the European Union and Other International Donors

- Provide funding for medical, psychological and social support programs in Lebanon for male survivors and GBT survivors of sexual violence, with increased emphasis on trauma therapy, without diverting the funding from services for women and girls.

Methodology

This report focuses on the experiences of gay and bisexual men and transgender women who are survivors of conflict-related sexual violence in Syria in order to highlight the specific vulnerabilities surrounding real and perceived sexual orientation and gender identity. While this report focuses on GBT survivors, people with non-normative sexual orientation and gender identity are not the only targets of conflict-related sexual violence. Therefore, this report also includes experiences of heterosexual and cisgender men who are survivors of sexual violence in Syria.

The research in this report focuses on (i) sexual violence against men and boys and transgender women that occurred in Syria from the beginning of the Syrian conflict (March 2011) until the survivors fled to Lebanon and (ii) the challenges male survivors face in accessing psychosocial and physical health services in Lebanon.

The report is based on research conducted between December 3, 2018, and February 14, 2019. Human Rights Watch interviewed 42 Syrian survivors of sexual violence who currently live in Lebanon and 2 survivors who resettled in the Netherlands and Italy as well as 20 case workers, social workers, doctors, psychologists and psychiatrists working for local and international humanitarian and human rights organizations in Lebanon.

Among the 44 interviewees, 40 are gay and bisexual men, transgender women, and non-binary individuals and 4 are heterosexual men. Transgender women were included because, although they identify as women, perpetrators perceived and targeted them as gay men. The interviews in Lebanon were conducted between January 17, 2019, and February 14, 2019. Interviews with resettled survivors occurred between December 3, 2018, and January 28, 2019.

All interviewees were above age 18 at the time of interview; however, some gay, bisexual, non-binary and transgender interviewees were minors when they were subject to sexual violence in Syria.

Interviews in Lebanon were in-person, while those with resettled individuals took place over Skype. In addition to the interviews, Human Rights Watch also obtained documents of four incidents of heterosexual survivors of CRSV from the Lebanese Center for Human Rights (CLDH), a Lebanese non-profit organization working with torture survivors. All documents were provided with the consent of the survivors.

Human Rights Watch contacted interviewees through the Lebanese LGBT organization Helem and other Lebanese and international organizations based in Beirut, including the Lebanese Center for Human Rights and KAFA (Enough) Violence & Exploitation.

Sexual violence also occurs in forced displacement settings. While many of the Syrian survivors interviewed by Human Rights Watch have also experienced sexual violence in Lebanon, we did not include those incidents in this report.

Human Rights Watch makes every effort to abide by the best practice standards for ethical research and documentation of sexual violence. The interviews were conducted by a female researcher and a female interpreter, with Arabic to English translation. All interviews were conducted privately. One heterosexual survivor was accompanied by his case worker at his request.

Human Rights Watch obtained informed consent from all interviewees and provided explanations in Arabic about the objectives of the research and explained that interviewees’ accounts would be used in a report and related materials. All interviewees were informed that they could stop the interview at any time and decline to answer questions they did not feel comfortable answering. Human Rights Watch met interviewees in discrete and safe settings and used interview techniques designed to minimize the re-traumatization of the survivors. In cases where survivors said that they were experiencing or appeared to experience significant distress, the researcher limited the questions about the experience of sexual violence or ended the interview early.

For security reasons, pseudonyms are used for all interviewees.

Human Rights Watch did not compensate interviewees but did cover transportation costs for interviewees who traveled to meet the researcher.

A Note on Gender Identity and Expression

This report addresses human rights abuses faced by individuals who identify as men or boys or who were assigned a male sex at birth. This includes gay and bisexual men, as well as transgender women and non-binary individuals. For example, transgender women and non-binary people assigned male at birth do not identify as men or boys. However, we have included them because they were perceived as effeminate men, or gay men, and subject to sexual violence on that basis.

We start from the premise that everyone has a gender identity. Most people identify as either female or male, though some may identify as both or neither. If someone is labeled “female” at birth but identifies as a man he is a transgender man (or transman). If someone is labeled “male” at birth but identifies as a woman she is a transgender woman (or transwoman). They may or may not take steps to physically alter their bodies, such as undergoing hormone replacement therapy (HRT) or sex reassignment surgery (SRS). The term “cisgender” (non-transgender) is used for someone who identifies with the same gender, male or female, as the sex they were assigned at birth.

In this report, by gender expression, we mean the external characteristics and behaviors that societies define as “feminine,” “androgynous,” or “masculine,” including such attributes as dress appearance, mannerisms, hair style, speech patterns, and social behavior and interactions. In the majority of the cases, the transgender women interviewed did not dress as “feminine” in an effort to conceal their gender identity; they dressed in more “masculine” attire, in accordance with the male sex they were assigned at birth. At the time they experienced sexual violence, according to their accounts, they were expressing a more masculine identity through their attire; however, their mannerisms, hair style, speech patterns, and social behaviors and interactions were perceived as “feminine.”

Gender identity is not the same thing as sexual orientation. Like cisgender people, transgender people may identify as heterosexual, homosexual, bisexual, or asexual; that is, they may be attracted to people of the opposite gender, the same gender, both genders, or neither.

I. Background

Conflict-Related Sexual Violence Against Men and Boys

Rape and other forms of sexual violence have been used as a tactic and practice of war in different conflict settings by a range of perpetrators against women, men, girls, and boys.[5]

CRSV against men and boys occurs in different forms. Until now, research shows that in conflict and forced displacement settings, men and boys are subject to rape (such as penetration of organs or other objects) and other forms of sexual violence (such as forced nudity, genital violence, enforced rape of others, forced witnessing of sexual violence, threat of rape, castration, and sterilization) in detention settings by state security forces, non-state actors and other detainees, in non-detention settings by non-state armed groups, by the military and the community, and within the military by other combatants.[6]

Conflict-related sexual violence against men and boys is widespread around the world; however, it is at times misunderstood and underreported for various reasons.[7]

CRSV: A Male Issue Too

Historically, authorities, service providers, and researchers have examined sexual violence primarily as a crime committed against women and girls.[8] Women and girls are disproportionately targeted by CRSV, but men and boys are also targeted for such violence.[9]

In recent years this has started to change as humanitarian service providers and researchers dedicate more attention and resources to the issues affecting male survivors. UN Security Council Resolution 2467 adopted in April 23, 2019, and the 2019 Annual Report of the UN secretary-general on conflict-related sexual violence recognize that men and boys are also targets of sexual violence, both in conflict and post-conflict settings, including in detention and by non-state armed groups.[10]

Some of the same gender norms that drive sexual violence against women and girls—as well as the norms that denigrate homosexuality—underpin patterns of sexual violence against men and boys.[11]

Gender stereotypes, and accordingly the social roles assigned to men, feed many myths that exist around sexual violence against men and boys. A 2017 UNHCR report includes a list of common myths about sexual violence against men and boys. These myths include:

- Sexual violence, particularly in conflict, always involves male perpetrators and female victims;

- Sexual violence against men and boys in conflict is rare;

- Male survivors are less affected by sexual violence than female survivors;

- Male survivors of sexual violence are or will become gay or bisexual;

- Male perpetrators of sexual violence against other males are gay or bisexual. [12]

Dispelling myths about male invulnerability will encourage research on and enhance responses to conflict-related sexual violence directed against men and boys. Scholars argue for more gender-inclusive formulations of conflict related sexual violence, and a more nuanced understanding of gendered power dynamics. Chris Dolan, director of Refugee Law Project, an organization that has worked for decades with male survivors in Uganda, argues:

[It] requires us to break down conceptual barriers, foremost of which are the assumption that gender power and inequality is unidirectional, the belief that power always has the same biological targets and the related view that (sexual) violence against women and children is the paradigmatic expression of these unidirectional inequalities… Men and boys can therefore be vulnerable, particularly in contexts of conflict designed to destabilize the status quo; their privilege in peacetime can become the source of their vulnerability in conflict.[13]

Purpose of Sexual Violence Against Men and Boys

Sexual violence scholars have argued that the use of sexual violence against men and boys is often as a tool to dehumanize and humiliate them, while reinforcing the power dynamics between male survivors and perpetrators.[14] In other words, through rape or other forms of sexual violence, the perpetrator demonstrates dominance over the survivor.[15] A study by the UN secretary- general in 2002, pursuant to Security Council resolution 1325 (2000) states:

The sexual abuse, torture and mutilation of male detainees or prisoners is often carried out to attack and destroy their sense of masculinity or manhood.[16]

In some cultures masculinity is often linked to power and dominance, and can be constructed as the ability to exercise power over others.[17] Heterosexual men represent the strength and power of the family and the community, and are expected to protect not just themselves but others.[18] Sexual violence, in disempowering men, can also disempower the broader community.[19] Legal scholar Sandesh Sivakumaran explains:

At an individual level, the male is stigmatized as a victim and the community is informed that their male members, their protectors, are unable to protect themselves. And if they are unable to protect themselves, how are they to protect ‘their’ women and ‘their’ community? In this way, the manliness of the man is lost and the family and community are made to feel vulnerable. Disempowerment of the community is again had through the dominance over its male members.[20]

As political science scholar Michele Leiby states: “Norms of hegemonic masculinity exclude the very possibility of male weakness, victimization, or sexual penetration.”[21] In many societies, people often believe that men who have been raped or subject to sexual violence are not “real men” because “real men” can protect themselves from such violence.[22] Sivakumaran explains:

[S]exual violence may be considered to be inconsistent with certain societies’ understandings of masculinity. Victims are considered weak and helpless, while men strong and powerful. Masculinity and victim-hood are thus seemingly inconsistent.[23]

When it comes to gay or bisexual men, transgender women, and non-binary people, violence can also be triggered by antipathy toward non-normative sexual orientation or gender identity and expression. Rape and other forms of sexual violence are also motivated by homophobia and transphobia. Gay, bisexual and transgender (GBT) people are targeted for “deviating from expectations around masculinity or because they are perceived as feminine.”[24]

Sexual violence against men and boys in general is also carried out through stigma and norms that denigrate same-sex sexual relations. Dustin Lewis, senior researcher at the Harvard Law School Program on International Law and Armed Conflict, writes:

[I]t would be inaccurate to say there is no ‘gay’ or ‘homosexual’ component to male-male sexual violence. To the contrary, it is in part precisely because of the potential negative effect of imputing a ‘gay’ identity or ‘homosexual’ behavior to the victim that male-male sexual violence can be psychologically and emotionally damaging….[25]

In many societies, gay men are considered “less masculine” than heterosexual men.[26] Heterosexual male survivors of sexual violence may question their masculinity (and therefore their societal power) and sexuality, part of which is driven by stigma against homosexuality.[27] Sivakumaran argues:

…there is a ‘taint’ of homosexuality about the victim of a male/male rape. Indeed, according to those who work with survivors of male/male rape, a commonly asked question is whether the victim is gay as a result of the rape.[28]

Another false assumption is that only GBT individuals are targets of rape and other forms of sexual violence.[29] Men and boys, regardless of their sexual orientation and/or gender identity are targets of rape and other forms of sexual violence, especially in conflict and post-conflict settings.[30]

However, evidence suggests that gay and bisexual men and transgender individuals are more vulnerable to this type of violence because they are targeted for violence, with or without conflict, based on their sexual orientation and/or gender identity.[31] Evidence shows that with armed conflict, targeting of gay men, transgender men, and women increases.[32]

Underreporting and Misrepresentation

Like all sexual violence, conflict-related sexual violence is severely underreported, and even more so when men and boys are victims. Moreover, conflict-related sexual violence against men and boys is often recorded in surveys, studies, and legal proceedings only as torture or other forms of violence, thereby obscuring the degree to which they experience it and hindering provision of appropriate and specialized services linked to the sexual nature of the crime.

Therefore, the numbers do not reflect the reality.[33] As in the case of women survivors of sexual violence, shame and stigma around this issue, fed by gender stereotypes, prevents male survivors from coming forward.[34] “I lost my dignity,” a paper submitted by the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic (Syria COI) to the Human Rights Council, states:

Male victims also suffer long-term physical and mental health issues including depression, many times compounded by an inability to admit to others what they experienced, in large part out of fear that perceived loss of masculinity would prevent them from fulfilling traditional gender roles.[35]

Even if male survivors do report incidents of sexual violence, they may report it as torture or humiliation instead of expressing the sexual aspect of the violence, due to fear of stigmatization and re-victimization.[36] Dolan explains:

The absence of data on male victims is not an objective reflection of levels of violence, but rather a symptom of immense difficulty—both on the part of the male victims themselves and, for different reasons, on the part of those tasked with shaping GBV [gender-based violence] support interventions—in acknowledging that men too can be rendered vulnerable by virtue of their gender.[37]

In order to overcome the challenges of underreporting and data collection on CRSV against men and boys, researchers may have to modify their methodologies. For example, while conducting research on sexual violence against Rohingya men and boys in 2018, the Women’s Refugee Commission researchers realized that participants were reluctant to ascribe the term “sexual” to the experiences of men and boys.[38] So they changed their approach and used the word “torture” (such as, torture to the genitals) during interviews, instead of using the terms “sexual” and “rape.” As a result, interviewees spoke about genital mutilation and other forms of sexual violence. By reformulating their methodology, they were able to collect evidence about CRSV against men and boys.[39]

In addition to survivors’ perceptions and terminology potentially impacting how these incidents are understood, service providers, health care personnel and humanitarian staff also often fail to recognize rape and sexual violence against men and boys as “sexual violence,” due to lack of training or reluctance to believe that men can be raped or sexually assaulted.[40]

Sexual violence against men and boys—just as against women and girls—may be used as a form of torture.[41] Recognizing that rape and other forms of sexual violence can amount to torture is important for the application of legal instruments that prohibit torture and can trigger international action for accountability.[42] In addition, the legal category of rape is not available to men in many national law settings, and torture is used more often in advocacy and criminal proceedings. Therefore, crimes that amounts to torture should be labelled as such.

However, approaching conflict-related sexual violence only through the lens of torture may obscure the gendered and sexual nature of the violence.[43] In order to ensure accurate reporting and documentation of the violation, and provide a response tailored to the needs of survivors, the gendered and sexual dimensions of CRSV need to be taken into account.[44] As stated in a 2016 report of the UN special rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment on punishment:

Full integration of a gender perspective into gender analysis of torture and ill-treatment is critical to ensuring that violations rooted in discriminatory social norms around gender and sexuality are fully recognized, addressed and remedied.[45]

In many studies, data related to CRSV against men and boys has been coded and documented only as “torture,” which has led to misrepresentation in reports of the nature, extent, and patterns of sexual violence perpetrated against men during conflict.

For example, truth commissions’ reports on crimes during the civil wars in El Salvador and Peru states that 1 percent and 2 percent of survivors of sexual violence, respectively, identified in the testimonies were male. However, a re-analysis and re-coding of the testimonies revealed that survivors of sexual violence during the armed conflicts in Peru and El Salvador were actually male in 53 percent and 22 percent, respectively, of the total cases of sexual violence.[46]

While re-analyzing the testimonies of the male survivors in Peru and El Salvador, scholar Michele Leiby took into account multiple forms of sexual violence, including rape and gang rape, sexual torture, mutilation, sexual coercion, and a general category for unspecified forms of sexual violence.[47] Cases of sexual violence such as sexual torture that had been overlooked or miscoded in research on Peru were also added to Leiby’s analysis.[48] During the re-analysis of testimonies, Leiby paid particular attention to key facts such as how the survivor came to be targeted for violence, what the survivor was doing at the time of the attack, who was present during the act of violence and exactly where the violence was perpetrated.[49]

A nuanced examination of sexual violence against men and boys helps erode myths around male sexual violence. Practically speaking, it provides an evidence base to design appropriate prevention and response measures and critical services for male survivors of sexual violence, such as appropriate medical and psychosocial care. For example, the All Survivor Project’s research on sexual violence against men and boys in Central African Republic in 2018 provides solid evidence on the gendered nature of CRSV. All Survivors Project has been using its research findings to create spaces in CAR to improve services for male survivors of sexual violence with a survivor-centered approach.[50]

Background of CRSV Against Men and Boys in Syria

In the Syrian context, since the anti-government protests in March 2011, sexual violence has been used against women, men, girls and boys in house raids, checkpoints, and in detention centers as a widespread and systematic abuse by state and non-state armed groups.[51] The Syria COI has concluded that rape and sexual violence occurring in Syria amounts to war crimes and crimes against humanity.[52] In Syrian detention centers sexual violence is used against men and boys as a form of torture by Syrian authorities.[53] During interrogations to force detainees to confess and torture sessions in detention centers, men and boys have been subject to different forms of sexual violence, including:

- Rape, including with objects;

- Sexual harassment and humiliation;

- Genital beatings, burnings, electric shock and mutilation;

- Threat of rape against them and others;

- Forced nudity.[54]

The Syria COI has described rape and sexual violence against men in detention as follows:

Male detainees, including boys as young as 11 years, were subjected to a range of forms of sexual violence including rape, sexual torture and humiliation. Generally, rape of males took place during admissions to a facility—in these cases, the perpetrators were often pro-Government militias supporting the detention facility—during interrogations to force confessions, and occasionally even after detainees confessed to further humiliate or punish them. Upon arrival at detention facilities, men and boys were forced to strip, and often stand naked in front of others. In some instances, they described being submitted to unnecessarily intimate searches during which guards touched their genitals.

The most common form of male rape occurred with objects, including batons, wooden sticks, pipes, and bottles, a tactic which has been used during interrogations since early in the conflict.[55]

Syrian detention centers are not the only place where sexual violence is used against men and boys. In non-detention settings, men and boys have been subject to rape and other forms of sexual violence at checkpoints, during house raids and within the Syrian army.[56]

Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity, and Risks of Sexual Violence In the context of the war and before the war we were always persecuted.

—Sabah, transgender survivor, Beirut, January 2019

[I]t’s a shame to be LGBT [in Syria]. If you are LGBT you bring shame to the family and you should be killed. The family should wash the shame so that they can have friends again.

—Nur, Beirut, January 2019

Almost all countries in the Middle East and North Africa region criminalize some forms of consensual adult sexual relations, which can include sex between unmarried individuals, adultery, and same-sex relations. Laws that criminalize same-sex conduct not only render LGBT people vulnerable to violence by expressing official antipathy toward the population, but also prevent victims from reporting crimes to officials due to the fear of being punished rather than being protected. Just as such laws do so in peacetime, they can also contribute to use of sexual and other violence against LGBT people in wartime, contributing to both heightened vulnerability of LGBT people during conflict and reduced likelihood of them reporting sexual violence.[57]

Widespread animosity toward sexual and gender diversity goes hand in hand with violence against people based on their real or perceived sexual orientation or gender identity. The already-existing vulnerability of LGBT people—or those perceived or characterized as LGBT—increases in conflict and post-conflict situations, which are characterized by an increase in lawlessness.[58] In an environment without rule of law and amplified stigma, LGBT people may be particularly vulnerable when seen as “legitimate targets for violence.”[59] A 2015 report by the UN secretary-general on conflict-related sexual violence recognizes that sexual violence against LGBT people is heightened during conflict:

Torture and ill-treatment of persons on the basis of actual or perceived sexual orientation or gender identity is rampant in armed conflict and perpetrated by State and non-State actors alike, with rape and other forms of sexual violence sometimes being used as a form of ‘moral cleansing’ of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender persons.[60]

Similarly, in a 2019 report, the UN Secretary-General recognized “that lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex individuals are sometimes specifically targeted with sexual violence in conflicts” and recommended:

[M]ore consistent monitoring and analysis of and reporting on violations against lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex individuals, and the review of national legislation to protect lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex victims.”[61]

Syrian law reinforces discrimination and violence against LGBT people. Article 520 of the Syrian Penal Code 1949 states that “any unnatural sexual intercourse shall be punished with a term of imprisonment of up to three years.”[62] Article 517 of the code punishes crimes “against public decency” that are carried out in public with imprisonment of three months to three years.[63] Terms such as “indecency,” “immoral acts,” and “acts against public decency” may be arbitrarily interpreted to prosecute LGBT people for consensual sexual conduct between adults. Therefore, while article 517 does not specifically mention homosexual conduct, it may be used to imprison LGBT people in Syria. Human Rights Watch does not have evidence that these articles of the Syrian penal code have been used to prosecute same-sex sexual acts.

Sexual and gender minorities in Syria have suffered discrimination and persecution exacerbated by state-sponsored homophobia long before the war began.[64] Perpetrators include family members, community members, and authorities. [65] LGBT people are often seen as shameful and a disgrace to their families, which leads to rejection and, in some cases, death threats and being targeted for “honor killings.”[66]

Gay and bisexual men and transgender individuals are especially vulnerable to sexual violence during conflict.[67] Perpetrators target men who are gay or bisexual—or perceived as such—because they violate heterosexual norms and do not conform to social expectations of masculinity.[68] Individuals who are seen to fall short of dominant masculine ideals, including by exhibiting traits or behaviors that are typically viewed as feminine, are perceived as weak and hence vulnerable to abuse. [69]

According to the 2017 UNHCR report, as a result of the general increase in violence during the Syrian conflict, violence against the LGBT community in Syria has also increased.[70] The surveillance, entrapment, and public exposure of gay men has intensified.[71] GBT individuals are targeted by state and non-state armed groups based on their real or perceived sexual orientation and/or gender identity.[72] Evidence shows that they have been targeted for sexual and physical violence.[73] A 2014 Syria COI report states:

Men were tortured and raped on the grounds of their sexual orientation at government checkpoints in Damascus. In 2011, six homosexual men were beaten viciously with electric cables by security agents and threatened with rape.[74]

II. “Soft” Targets of Syria

Many interviewees describe “softness” as a marker of being gay or transgender or falling short of masculine ideals. Cases that Human Rights Watch documented show that although men and boys are stopped at checkpoints regardless of their sexual orientation and gender identity, gay and bisexual men and transgender individuals were often sexually and verbally harassed and sexually abused on the basis that they were “soft looking.”[75]

Some interviewees told Human Rights Watch that they would adopt self-censoring behavior to conceal their sexual orientation or gender identity in order to protect themselves at checkpoints or while they were serving in the military.[76] Some referred to this as acting like “real men” or suppressing behaviors that might be perceived as “soft.” Walid, a 26-year-old gay man, said: “When I was at checkpoints, I acted like a ‘real man.’ I act straight so they don’t [suspect] I’m gay.” He explained:

At checkpoints, they generally stop people who are dressed differently or people who take care of their appearances … people dress in Syria, somehow in a conservative way. So, wearing tight pants, wearing lots of perfume or fixing the hair—these are practices only for gay and trans people. [The police] also look at gestures. The way we sit and move our hands, body language. They target gay and trans people.[77]

Evidence gathered by Human Rights Watch show that GBT individuals in the military were specifically targeted on the basis of their sexual orientation and/or gender identity. Interviewees told Human Rights Watch that GBT men and boys who serve in the army are often subject to rape and other forms of sexual violence in military prisons, or by other soldiers in the army. “There were men who looked more soft, [appeared] to be like a woman more than a man, who didn’t have beards. They were harassed more than others. To tell you the truth, if their [the soldiers’] girls were absent, these men would be [become] the victim,” Hatem, a heterosexual survivor who served in the army, said.[78]

Some fled Syria out of fear of sexual violence in the military, if they joined up. Zakhya, a transgender woman, said: “I ran away [from Syria] because I didn’t want to be involved in the army.” She said people in her community told her the army would make her “become a man.” “They [people] said to me you become a man. You are straightened up when you join the army. If not you will be fucked [by other soldiers],” she said.[79]

Nur, a 25-year-old gay survivor, was detained in Palestine branch, a detention facility run by the Syrian Military Intelligence, in 2012 for being late for her military service.[80] Nur explained why she did not want to serve in the army:

I couldn’t hand myself to the army because we know in Syria what happens to people who are from the LGBT [community] that join the army. Like for example rape and insults. They use you as an object; but even more than [they do to] girls because we are guys and acting like girls. My friend had a personal experience with that. He was raped.[81]

Marwa, a transgender woman, said that she had to “act like a man” in order keep herself safe while she served in the Syrian army because she feared being sexually abused:

I had to shave my head and I had to pretend I was a man. But deep inside I felt like a female. I didn’t look like a woman in any way. I was acting like a man. Especially in the collective bathroom I had to act extra like a man.[82]

Apart from being targeted by Syrian forces at checkpoints, in detention centers and within the Syrian army, gay and bisexual men and boys and transgender individuals have also been targeted and executed by the Islamic State (ISIS), in areas under ISIS control. ISIS executed gay and bisexual men and transgender individuals by throwing them from high-rise buildings.[83] Amal, a 26-year-old transgender woman, was detained by ISIS and witnessed one of her gay friends being thrown from a high building to his death.[84] At the time, she also identified as gay. She managed to flee from ISIS.[85]

Khalil, a 21-year-old gay survivor was captured by ISIS with a group of people, including his boyfriend who was killed for being gay. He said:

I was detained by ISIS for three months for being part of protests. I was 15. I was detained with my friends. My boyfriend was thrown from a high building by ISIS.[86]

Family Violence and Discrimination

In addition to being targeted by state and non-state armed groups, gay and bisexual men and transgender women told Human Rights Watch that LGBT individuals in Syria are rejected, ostracized, and subject to violence by their family members.[87] Hostility from families is a compounding factor for vulnerability to violence, including sexual violence. Gay and bisexual men and transgender women interviewed by Human Rights Watch described being severely beaten by their parents, locked in their rooms and thrown out of their homes.[88] Some interviewees believed their parents had sent family members to Lebanon to kill them and feared being subjected to so-called honor crimes.[89]

Jamal, a 23-year-old gay man who has lived in Lebanon since 2014 with his siblings, told Human Rights Watch that after his brothers discovered his sexual orientation, they physically abused him:

My brothers recently found out that I am gay and they torture me about it. They beat me, imprison me at home and they have threatened to kill me. They follow me like my shadow.[90]

GBT survivors were blackmailed by their own family members and some were even handed to the intelligence forces or to the Syrian army by their own families so that they would be “fixed” or killed. Eight of the interviewees received death threats from their families when they learned about their sexual orientation and/or gender identity. Fahed, a 23-year-old gay man, received a threatening text message from his mother on September 5, 2018, when she learned that her son was gay:

May God break your heart, like you broke mine. You faggot, you effeminate. I give you only one week to leave the country [Syria] or else I will kill you myself.[91]

Fahed said:

My stepfather wanted to send shabiha [pro-government militia] to kill me and detain me. He put my name in all checkpoints and wanted to kill me. I left Syria on September 19, 2018.[92]

Nur told Human Rights Watch that her three brothers who also live in Lebanon and know that she is “part of the LGBT community” are still chasing after her. Two days before she spoke with Human Rights Watch she said someone tried to strangle her. The identity of the attacker is unknown but her friend who physically defended her from the attack told Nur that the attacker looked like her brother.[93] She said:

I am always scared. When I walk in the street I always look left and right as if I did something wrong. If I get killed, nobody will know who killed me and nobody will bury my body.[94]

III. Sexual Violence in the Syrian Conflict

Syrian forces have used rape and other forms of sexual violence to harass, intimidate, and torture men and boys in intelligence branches, military and unofficial detention centers, central prisons, checkpoints, and in the Syrian army.[95] Interviewees told Human Rights that men and boys were raped, sexually and verbally harassed, threatened with rape of themselves and their loved ones and were subjected to forced nudity.

Men and boys, regardless of sexual orientation or gender identity, were subject to sexual assault and rape in detention centers and checkpoints. Interviewees believed that perpetrators increased or intensified the violence once they learned that the interviewees were gay, bisexual, or transgender. GBT survivors who served in the Syrian military were subject to rape and other forms of sexual violence by other army members and in military prisons. Three survivors were detained in Tadmur Prison and two were detained in the Palestine Branch.[96]

Rape

Rape in Intelligence Branches, Military Prisons and Central Prisons

In Syrian intelligence branches, officers have used rape as a means of torturing men and boys during interrogation sessions or torture sessions .[97] Human Rights Watch has been documenting these incidents, as well as sexual violence and abuse of women in detention, since the beginning of the Syrian uprising in 2011.[98]

Interviewees told Human Rights Watch that the intelligence officers would rape detainees by penetrating their rectums, often with sticks or sharp objects. Evidence show that security forces used rape against all detainees, regardless of their real or perceived gender or sexual orientation. Yousef, a 28-year-old gay male survivor of sexual violence, told Human Rights Watch he observed officials in the Al-Khattib Branch, a detention facility run by the General Intelligence, targeting women, girls, men, and boys with sexual violence, using it on “anyone who is against them.”[99]

Some interviewees said that they were first detained in a detention facility run by the intelligence agencies (mukhabarat) or the military and then were transferred to central prisons, official government detention facilities. It was not uncommon for detainees to be transferred between multiple detention facilities.[100] Some interviewees were detained and released several times by the same security forces. Interviewees told Human Rights Watch that in central prisons—as in military detention—once the officers or fellow detainees knew about a prisoner’s sexual orientation or gender identity or perceived it as non-normative, they specifically targeted such individuals with sexual violence, including rape.

While all detainees faced the prospect of abuse, GBT survivors told Human Rights Watch that they believed that they were subject to violence of increased intensity once their sexual orientation or gender identity was revealed. For example, when perpetrators checked their phones for evidence of same-sex attraction or behavior, subsequent sexual violence would intensify.

For example, Yousef said that he was detained by mukhabarat during an anti-government protest in the beginning of 2012 in Damascus. He told Human Rights Watch that although he was not targeted by the intelligence agency because he was gay, once they learned about his sexual orientation through checking his phone, violence during interrogations increased drastically. He explained that after intelligence officers detained him for joining the protests, they beat him severely until he confessed to acts that he did not commit. “I was being beaten and I was going to die. At the end you want them to stop, so you start saying yes to things that you have never committed,” he said. And once they discovered his sexual orientation, the violence intensified:

They said to us that they checked our phones and told us [Yousef’s detained friends], ‘You are not only against what is right; but you are also faggots.’ All the aggression was multiplied by 10 I would say. They were happily doing it. They were of course raping us with sticks.

They rape you just to see you suffering, shouting. To see you are humiliated. This is what they like to see. They had a stick inside my anus, and they started saying, ‘This is what you like, don’t you like it?’ It went up until my stomach.[101]

Intelligence officers also threatened to reveal his sexual orientation to his family. Yousef told Human Rights Watch: “They said, ‘We are going to bring here your dad to see that you are gay and they will disown you and you are disgusting.’”[102]

Intelligence officials detained Yousef in the same facility as a gay friend of his, who they had also arrested during the same protest. Yousef told Human Rights Watch he heard from his friend while in detention that he was also being raped regularly. [103]

Sabah, 40, a transgender woman, was detained in Sednaya, a military prison in Damascus, before the Syrian conflict started. Sabah was arrested in 2007 for hiding a friend who was chased by the police for reasons unrelated to the conflict. She was taken to military prison because at the time she was serving in the army and was on leave. After spending a few years in Sednaya prison she was transferred to Hama Central Prison after the conflict started in 2011, where other detainees raped her multiple times. Sabah stayed in the central prison until 2015. “I was always soft looking. It deprived me from my family and my life,” she said.[104] Sabah explained:

I was almost 32. Even if you are caught with other people, they would interrogate you individually. It is the same routine that applied on everybody just for being gay or trans. We are beaten, treated with violence and insulted. Not by one person but by many. They could tell from our appearance [that we were trans or gay]. Perpetrators were both guards and prisoners. If someone [other prisoners] asked for me, I had to go and see them among the normal [other] prisoners [for them to abuse or rape me]. You couldn’t say no or we would be thrown from buildings, slaughtered, or beaten with sharp objects.[105]

Human Rights Watch documented cases where GBT survivors said they were subject to rape by other fellow prisoners in central prisons when they were minors or were forced to rape each other. Zarifa, a 22-year-old gay man, who uses female pronouns, said that her family complained about her to the Syrian government once they realized her sexual orientation, when she was around 13 years old.[106] Intelligence officials detained her and kept her in a solitary cell underground for a week. Then she was transferred to a central prison. She said:

A week later they took me to a collective prison [central prison] where I was raped almost every night. I don’t even know if the mukhabarat knew about it. People in the prison not the guards [were raping me]. I was with adults. There were also many minors with me. I believe that they faced the same things like me…. I meant minors were being raped at night…. Rape was committed by adults in the prison and the rest of the violence by guards. I was in the prison until 17 years old—late 17.[107]

Naila, a 21-year-old transgender woman, was an activist and was detained multiple times for taking part in demonstrations after 2011. Naila said that plain-clothed men broke into her house in Homs and saw pro-opposition newspapers, magazines, and signs she had used during protests, as well as articles about gender identity that she brought from Beirut. Naila said that she was kept for three weeks in February 2013 in a police station in rural Homs with the accusation of “delinquency under the pretext of fomenting revolution.” Authorities released her after three weeks, then apprehended her again in March 2013. As before, non-uniformed men entered her home and apprehended her. “They took me again for two weeks and this time I didn’t know why.”[108] She said prisoners, guards, and other officials in the prison raped her, multiple times .[109] Naila said:

I was kept in room number 14. It was on the 18th of March 2013. The room was full of men. I didn’t find a place to sleep. I sat by the bathroom and hid my chest with my legs. I was afraid of them all. They were all staring at me. My skin was soft, and I had long hair. I had prominent female features at the time. They were all laughing at me and mocking me and making sexual innuendo jokes. I had a panic attack at this moment. I kept calling the guard, but he never responded to me. I was scared, lost and locked. The room was very small. There were 25 men inside. Then they started taking off their shirts. Some of them touched me. I was suffocating and scared. It was disgusting. I never stopped calling the guard. But to no avail. Then they dragged me to the middle of the room. Some of them lifted me up and tore my clothes apart. They raped me.[110]

Naila said that another day a man she identified as the head of the prison told the guard to take her to room 9 “because room 14 took what they wanted.”[111] Naila continued:

As soon as I entered the room I understood why I was there. I wasn’t alone experiencing this. There was a gay person in room nine and he was also in the middle of the room and going through the same things I went through. That room was bigger. It had 30 men inside. When they saw that there are two ‘soft’ people among them, they put us in the middle of the room of course without food or water and the series of rapes started again. They forced me with the gay person to have sex in front of them while beating us and cutting us with blades. Then they brought the stick of a mop and they inserted it in our anus. A strong bleeding started, and we were mutilated.[112]

Naila said that then she was taken to an individual cell where she was raped by other prisoners, guards, and people she thought were high-ranking officials. Naila said:

They woke me up and took me to room five. It was an individual cell. I thought I would be alone, but they let in someone every single day, one or two people. Guards, prisoners, high ranking officials working at the police station. At the end I lost the power to resist. I just surrendered. I was covered in blood the whole time.[113]

Rape in the Syrian Army

Some survivors Human Rights Watch interviewed served in the Syrian army after the uprising started in 2011. Some interviewees had friends who had served in the army and were, they believed, raped because they were gay, bisexual, or transgender. Some fled the country because they were called to the army for the first time or were called to serve again as a reservist.[114]

Interviewees told Human Rights Watch that GBT people were subjected to sexual violence in the army and military prisons because of their sexual orientation and gender identity. Interviewees said this was common knowledge and that most GBT people fled the country due the fear of joining the army. Interviewees said that they or their friends who served in the army were taken to Tadmur Prison and Palestine Branch because they were GBT.

Toufiq, a 25-year-old queer survivor, fled the army after one month of service and came to Lebanon in November 2017. Their family had forced them to join the military after discovering their relationship with another man.[115] “I couldn’t handle being in the military because I was subjected to sexual assault,” they said. “I was harassed by the soldiers I stayed with,” they said, adding that they shared a room with three other male soldiers. “I did not have a beard at the time so they thought I was soft,” they said. “They did everything without my consent … intercourse … sexual relationship.”[116]

Halim, a 30-year-old gay man, served in the Syrian army from 2010 to 2011. Fellow soldiers assaulted and raped him during that period, because of his sexual orientation. Halim said:

I was assaulted when I was serving in the military. Just because it showed that I was different. First day I came to join military service, I had fashionable pajamas. Soldiers said that I looked like a girl in them.… I told them that I dance. I stood in the middle and started dancing…. Many of the soldiers slept with me by force.[117]

Rape at Checkpoints

Interviews conducted by Human Rights Watch show that although men and boys, regardless of sexual orientation or gender identity, are targeted at checkpoints, gay, bisexual and transgender women are targeted for their “soft looks.”

“If we go down the street and wear tight pants, they [security forces] would call us on purpose to provoke us, beat us and check our identities. I was stopped at checkpoints many times,” said Sayid, a 28-year-old gay man.[118]

Human Rights Watch documented one case of rape that occurred at a checkpoint in Damascus. Rima, a 20-year-old non-binary survivor, explained how a soldier at the checkpoint apprehended and detained her in 2014, when she was 15:[119]

Once my sister was stopped at the checkpoint. The soldier asked to see her mobile. He saw on her mobile my picture standing on the balcony and wearing shorts, without hair on my body. He asked, ‘Who is this?’ and she said, ‘My brother.’ They came to our house and took me under the order of the head of that checkpoint. When we arrived at his office he asked me to take off my pants and my T-shirt. Then my boxers and all my underwear. Then he made me sleep with him. He kept me 10 days, having sex with me 3 to 4 times a day. Whenever he felt like it. He kept on saying, ‘I will shoot you with your parents in your house if you tell anyone. I don’t care, as if you are a dog that perished.’

When he released me, he threatened me, instructing me to not tell my parents [about what he did to me] or he will kill them. He said, ‘Every time I call you, you have to come or I will put your name on [the list at] all checkpoints.’ He kept calling me and I went every time. I was scared for myself and my family.[120]

Electric Shock, Beating, and Burning of Genitals

In Syrian detention centers, sexual abuse to male genitalia by security personnel, including beatings and electric shock, has been documented as one of the common ways of torturing men and boys.[121]

Men and boys are sexually abused by Syrian forces in their genitals, regardless of their sexual orientation and/or gender identity, often to force confessions during interrogations or torture sessions. Five survivors told Human Rights Watch that they were subjected to beatings and electric shock on their genitals. Some GBT survivors told Human Rights Watch that once the security officers learned that they were GBT, the violence increased.

Nur, a 25-year-old gay survivor who uses female pronouns said that she was stopped at a checkpoint in Daraa, in 2012 for being late for her military service and was taken to the Palestine Branch. She said that the beatings she received increased drastically once her sexual orientation was discovered. Nur explained:

I was supposed to hand myself to the army. But I didn’t do it and my name was [on the list] at the checkpoint. That’s why they arrested me. They beat me and what not. At first, they beat me on my private parts … first because I didn’t hand myself to the army... When they learned I was part of the LGBT community, they started beating me double. Whoever went in or went out [of the checkpoint facility] beat me.”[122]

Some survivors told Human Rights Watch that they were subjected to this type of violence from the very beginning of their detention because security officers knew about their sexual orientation and/or gender identity.[123] Zarifa told Human Rights Watch that intelligence officers used electric shock all over her body. She said:

They tortured me. They kept me locked. They beat me. They used electricity on me everywhere. They detained me because of my sexual orientation. I wasn’t the only one to be tortured because of that reason [sexual orientation].[124]

Forced Nudity

Interviewees told Human Rights Watch that in Syrian detention centers, security forces would force detainees, regardless of their sexual orientation, to take off their clothes, leaving them only in their underwear or totally nude. Human Rights Watch documented five cases of strip searches that amount to sexual violence, forced nudity in crowded rooms in detention centers, and forced nudity in front of other soldiers in the army.

Ghada, a 37-year-old transgender woman detained in 2012 in Damascus for three months, told Human Rights Watch that the detainees in the Palestine Branch were forced to strip down to their underwear in a room with hundreds of people. Ghada said:

Intelligence detained me in the Palestine branch. Very bad treatment. We were forced to be nude. We were only in our underwear. It was very hot at the time. We were 250-300 people in a small room. We couldn’t even move. We were like eggs [packed in together].[125]

Officers in detention centers would ask detainees to take of their clothes and make “safety movements,” which is to squat up and down in front of the officers. Halim, who was detained in an Airforce Intelligence Branch in 2011, also explained how the intelligence officers asked him to do “safety movements,” while officers exchanged gestures, such as winking at each other, that would humiliate Halim. At the time, Halim was serving in the army. The intelligence detained Halim because a fellow soldier told an officer that Halim had cursed the officer’s sister and President Bashar al-Assad’s sister. Halim said:

They didn’t tell me that they were from intelligence. They took me in a car with black windows and blindfolded me. I stayed in a small room inside the Airforce Intelligence Branch for 29 days. It is known to be the strongest intelligence force in Syria. They say that those who go there are considered missing and those who get out are newborns. They have it written on the walls. They made me take all of my clothes off several times and asked me to go up and down while they watched me. I don’t have hair on my body [which made me look ‘soft’]. The officers winked at each other.[126]

Interviewees also described how officers in military prisons used forced nudity to degrade GBT survivors specifically for their sexual orientation and/or gender identity. Some GBT survivors said that officers in the Sednaya military prison forced those detained because of their sexual orientation and gender identity to stand naked in the middle of the soldiers so that they could humiliate them and spit on them. Sabah explained how Syrian security forces treated detainees they had identified as gay or trans:

In the military prison [Sednaya] they [security forces] beat us [LGBT], made us take all our clothes, mocked us, tied us to the ceiling, made us strip in front of four other soldiers and have them spit on us, humiliated us by insulting our sisters, mothers, and the rest of the family. I wished I would die before hearing these words. Even just the fact of having to undress in front of four people staring at me was very painful. I didn’t choose to be like that [LGBT]. Why are we different? Just because we are trans and gays? I couldn't speak up. I was under the mercy of prison guards and I was alone and helpless. In Syria you can’t even speak. We were more than one person…. Being gays, we were isolated from the rest of normal people. We were kept in one room and locked up as if we were a virus.[127]

Ghada told Human Rights Watch that she was sexually abused during her detention in Palestine Branch in 2012. She said that, upon arrival at the prison, detainees are taken for questioning before being brought to another room where they are stripped and body-searched. She described how a male officer searched her:

I wasn’t sure whether it was typical treatment because I was alone. He was checking my genitals with his fingers from the front and the back. He pressed his small beard against my skin. I was naked. He said to me, ‘Bend down.’ Then he put both his hands on my shoulders and came close to me from the behind. I felt it was strange, but I couldn’t show him I was bothered. This happened in an office in the detention center…The door was locked. He pressed his penis against my butt. Had I cooperated he would have done something [more].[128]

Threat of Rape

Five interviewees said that officers would threaten to rape their mothers or sisters during interrogations at detention centers and civil prisons or during stops at checkpoints. For example, Nabih, a 41-year-old heterosexual man, was threatened with the rape of his sister and mother when he was arrested by the Criminal Security branch of the Syrian Army in 2011 in Homs.[129]

Jamal, his sister, his brother, and his brother’s wife were stopped at a checkpoint in 2011. The officers threatened to rape Jamal’s sister and sister-in-law. Jamal described what happened when the group returned to check on their house in Hama after having been displaced by the war:

We were four, my brother and his wife, my sister and me. We were stopped at every checkpoint because our ID said that we were from Hama [a city in Syria]. We were accused of hiding weapons in the mountains. They took me and my brother away. They took us in the trunk of a car, blindfolded us and beat us. They threatened us and took our money. They said, ‘If you stay in the city one more day, we will make you regret it. We will rape your women.’[130]

Intelligence officers threatened Yousef, a 28-year-old gay man, during interrogation, with the rape of his mother and sister. Yousef said: “They want to get you annoyed. They use your sister’s name, your mom’s name. ‘We are going to do this [rape] to her,’ they say.” [131]

Interviewees told Human Rights Watch that the Syrian Security forces also threatened to rape the interviewees themselves. Jordan, a 24-year-old gay man, said:

One of the soldiers at the checkpoint tried to rape me. I wasn’t the only one who was stopped. They asked for our identity cards and military booklets. They took me inside where they check names. They said, ‘You are a faggot. Come let me show you. Come try me.’[132]

Sexual Harassment

GBT interviewees told Human Rights Watch that they were constantly subjected to verbal and physical sexual harassment in their families and communities, at checkpoints, and in detention because they were viewed as “soft.” “They want to crush, diminish them,” said a case worker at the Lebanese Center for Human Rights describing how GBT men and boys were treated.[133] Officers at detention centers and at checkpoints and soldiers in the army would either physically or verbally harass GBT survivors by mocking their traits that were not “masculine enough.”

Majd, 24-year-old non-binary survivor said:

Once I was in Tartous and I was stopped at a security checkpoint. There were a bunch of soldiers securing the hospital. I wanted to go to the hospital, but they did not let me in. I was wearing shorts and a T-shirt, it was summer. He said, ‘You look like someone who is [here] to get fucked, not to get services.’[134]

GBT survivors said that verbal harassment based on their sexual orientation or gender identity terrified them because being identified as queer, in particular by security forces at checkpoints, could escalate into physical and sexual violence, arrest and detention.

Three interviewees told Human Rights Watch that, at checkpoints, security forces would ask for their phone numbers and addresses of GBT individuals. Interviewees told Human Rights Watch that security forces would either show up at their address or call them, instruct them to come to their facilities, and then rape or sexually abuse them.[135]

Omar, a 21-year-old gay man, explained how Syrian security forces targeted and verbally harassed him at checkpoints:

I was targeted at checkpoints because of my appearance. I was discriminated [against], bullied and mocked. They would ask me, ‘Why are you dressed like this? Why do you talk this way?’ They asked targeted questions: ‘Why do you wear tight pants? Why is your voice like girls? Why don’t you speak up? Give us your number and address.’ I always had to give fake numbers and addresses.[136]

|

Stories of Heterosexual Survivors This report focuses on the cases of GBT survivors; in other reports published by Human Rights Watch and other NGOs, evidence of heterosexual survivors’ experiences is featured.[137] Security forces stopped Abdallah, a 32-year-old heterosexual man, at a checkpoint in Hama governorate in 2012 and took him to a high school-turned-detention center, where they subjected him to forced nudity. Abdallah said: “I cannot describe how bad it was. I was humiliated. They made us take off our clothes. It was a big hall, so many people were taken. They would make us go all inside, totally naked, without our underwear.”[138] Security forces stopped Hatem, a 31-year-old heterosexual man, at a checkpoint in Idlib and the officers there threatened to rape his sister. He said: “I was stopped at checkpoints. If a man is accompanied with a woman, let’s say his sisters, they would start insulting his dignity in front of her by saying for example, ‘What if we took you sister and did ‘that’ to her.’ It happened to me.”[139] Criminal Security branch of the Syrian Army members arrested Nabih, a 41-year-old heterosexual man, in 2011. In detention, they beat him all over his body and raped him with an object. They threatened to rape his mother and sister, subjected him to forced nudity, and beat him with sticks while he was naked.[140] Intelligence officers detained Haytham, a 37-year-old heterosexual man, in June 2011 and took him to the Air Force Intelligence Branch in Damascus where they beat him on his genitals. Hayhtam said the officers lit a candle and forced him to crouch over it and that they forced him to watch intelligence officers rape a woman in the detention center. He was kept for 18 days, then released because his arrest was a case of mistaken identity.[141] |

IV. Impact of Sexual Violence

Although most of the sexual violence mentioned in this report happened several years before the interviews took place, interviewees told Human Rights Watch that the physical and psychological impact of the violence continued to linger and affect their daily life.[142] Some continued to experience physical symptoms resulting from injuries or physical trauma sustained during attacks. Many survivors described symptoms consistent with depression or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and in some cases contemplated or attempted suicide.

As in other countries around the world, survivors of sexual violence in Syria and Lebanon often face stigma and rejection by family and community members. As a result, many survivors said they did not tell their families about the violence, nor did they seek help.

According to research conducted by UNHCR, heterosexual survivors often do not tell their wives about what happened, fearful that the sexual abuse would diminish their “manhood,” and their role as a father.[143] Interviewees told Human Rights Watch that the stigma and shame of being subject to sexual violence compounds the fact that they are already stigmatized and rejected by their families on the basis of their sexual orientation and/or gender identity.

Physical Trauma

Many survivors whom Human Rights Watch interviewed suffered physical effects as a result of sexual violence, often resulting from anal rape. Many survivors said they experienced serious rectal bleeding during and after the attacks, as well as muscle pain and problems while sitting down and defecating.

“They brought the stick of a mop and they inserted it in our anus. A strong bleeding started, and we were mutilated,”[144] said Naila, who was gang-raped in a civil [central] prison as a minor.

Yousef also experienced serious injury in his anus and internal organs because intelligence officers raped him multiple times with a stick in 2012. Yousef explained:

When they get you down, the stick is the most terrible thing.... I still have problems with my anus now. It is ruined forever. Sometimes I bleed. So I had infections inside, because all the stuff they inserted [in me] was very dirty. It happened on multiple occasions. You don’t know when and how [they’re going to do it]. You don’t have any rights there.[145]

After Yousef was released he said that he underwent several rehabilitative surgeries in Syria. Although he was raped years ago and received treatment for his injuries, he said that, in addition to rectal bleeding, he still has pain when sitting because of the abuse he experienced:[146]

Because I was beaten on my testicles, combined with how I was sitting [how they made me sit] for a long time, I had a hernia…Because of the sticks [used to rape me], I have bruises inside. I couldn’t go to the toilet. It was really bad.[147]

Interviewees said that the beatings Syrian security forces subjected them to all over their bodies and especially to their genitals resulted in serious injuries, such as bruises and broken bones. Even in cases where these healed over time,[148] six survivors said they still suffer from severe pain.[149] A case worker from the Lebanese Center for Human Rights told Human Rights Watch that many clients who are male sexual violence survivors had suffered from injuries and ongoing symptoms such as testicular varicose veins, hypertension, injured spines, and gastric pain.[150]

Interviewees declined to discuss their HIV status or any sexually transmitted infections. However, male survivors face a heightened risk of acquiring sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and HIV.[151]

Psychological Trauma

Almost all survivors Human Rights Watch interviewed said they suffer from symptoms consistent with trauma or depression, including inability to sleep, memory loss, loss of interest in interactions of a sexual nature, guilt, loss of hope, loss of appetite, paranoid thoughts and flashbacks to the traumatic experience.[152] Seven survivors said they had contemplated and some said they had attempted suicide. Interviewees also said that they developed fears of the army, of the color green (the color of Syrian military uniforms), and of any kind of authority figure, such as the police.[153]

Yousef, who experienced sexual violence in a Syrian detention center and currently resides in Netherlands, said:

I look behind me when I am walking. I still wake up at night. What would happen if it happens again? Once, the police [in Netherlands] stopped us just to check if we were okay. I stood and did not know what to say. This was a wake-up call. It [the trauma] is not over.[154]

Yousef explained how his life changed after he was raped and sexually abused by intelligence officers in 2012:

At the beginning I was so depressed. I questioned, ‘Why me?’ It affected my daily life and sexual life. I still feel pain. It is hard to remember, to talk about this. It is there, and it doesn’t go away. I hope it helps [others] really and it [rape and other forms of sexual violence in detention] will never happen. Every year I think it is not there, but it is there, the memory of it.[155]

Naila, raped by fellow detainees in a central prison multiple times when she was 15 years old in 2013, went through serious depression, had alcohol problems, and isolated herself from society following her detention. She told Human Rights Watch:

I went to Homs city. There I stayed for two months isolated, not talking to anyone, only drinking alcohol, I went into deep depression. I was remembering the very details of what happened to me day and night. Then I decided to stay awake during the night drinking alcohol and sleep during the day because the nightmares were so intense.[156]

Zarifa, who was subjected to electric shock and beaten on her genitals by intelligence officers in a detention center close to Qamishli said she developed a fear of electricity, and has sleeping problems: