(ニューヨーク)2018年7月29日に予定されているカンボジア総選挙は根本的な欠陥があり、国民は自らの政府を選ぶという国際法上の権利を否定されていると、ヒューマン・ライツ・ウォッチは本日述べた。欧州連合(EU)や米国、日本など各国は、今回の選挙プロセスが問題だらけのため、正式な選挙監視団を派遣しないと決定している。

選挙プロセスに関わる深刻な問題には、最大野党・カンボジア救国党(CNRP)への恣意的な解党命令や、主要な野党メンバーへの監視、脅迫、拘束、政治的な動機に基づく訴追などがある。主要な懸念としては、独立系メディアへの弾圧、メディアへの公正で平等なアクセスの欠如、言論と結社、集会を制限する抑圧的な法律などが挙げられる。中央選挙管理委員会は独立していない。国軍と警察の幹部は、与党・カンボジア人民党(CPP)への支持を訴える活動を全国的に展開している。

「カンボジア政府はこの1年、独立した意見や野党の意見を徹底的に弾圧し、与党が政治を全面統制する上での障害をすべて排除しようとしている」と、ヒューマン・ライツ・ウォッチのアジア局長ブラッド・アダムズは述べた。「最大野党の解党と党所属の政治家に対する政治活動の禁止という事態を見れば、今回の選挙がカンボジア国民の意志を反映するようなものにはなりえないことがわかる。」

2017年、カンボジア政府は野党・救国党への弾圧を強化し、脅迫や嫌がらせ、恫喝、監視、恣意的な拘束と訴追を行ってきた。2017年11月16日には、与党の統制下にある最高裁判所が、救国党が政府転覆を目指す「カラー革命」に関与しているとする政府の訴えを認め、救国党に解党を命じた。さらに裁判所は党所属の政治家118人について、今後5年間の政治活動を全面禁止した。

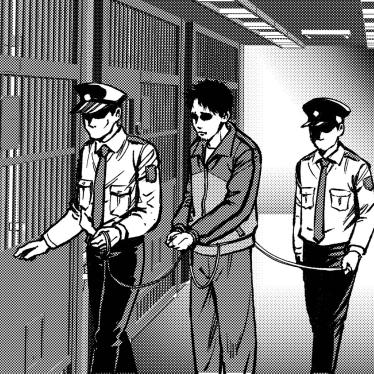

また、政府は救国党幹部に対し、政治的な動機に基づいた刑事訴追を行っている。元党首のサム・ランシー氏は複数の容疑を掛けられて亡命を余儀なくされた。2017年9月3日、警察と軍は現党首のケム・ソカ氏を、「カラー革命」に関与したとの容疑をでっち上げ、国家反逆罪で逮捕した。氏は首都プノンペンの家族と引き離され、トボンクムン州の刑事施設に現在も勾留されている。

救国党への解党処分を受け、米国は総選挙支援を全面凍結した。EUも中央選管の政治的偏向を問題として資金協力を停止した。これまで公的な選挙監視団を派遣してきたEUと各国政府は、7月29日総選挙の公平性を失わせる数々の構造的問題を理由に、今回は派遣を見合わせている。

カンボジアも批准する国連の市民的及び政治的権利に関する国際規約(B規約)第25条は次のように定める。「すべての市民は[略]次のことを行う権利及び機会を有する。[略]普通かつ平等の選挙権に基づき秘密投票により行われ、選挙人の意思の自由な表明を保障する真正な定期的選挙において、投票し及び選挙されること[略]。」

「カンボジアの今後を憂慮する各国政府は、今回の総選挙実施をカンボジア国民に対する破廉恥な詐欺的行為として非難すべきだ」と、前出のアダムズ局長は述べた。「救国党に解党命令が下されたことで、今回の総選挙は民主主義のまねごととなり、与党の勝利は予見可能になってしまった。カンボジアが真の民主主義を取り戻す手助けをするのか、実質的な一党国家の成立がもたらす人権状況の悪化を受け入れるのか、1991年のパリ協定の成立に多大な労力を割いた国々には決断が求められている。」

Barriers to Genuine Elections in Cambodia in 2018

The scheduled July 29 national elections in Cambodia will officially be contested by 20 political parties, but the dissolution of the main opposition party, the CNRP, means that the ruling CPP is effectively running unopposed. This and other actions by the Cambodian authorities, highlighted below, prevent the elections from being genuine, free, or fair.

Crackdown on opposition-friendly media

The CPP has long maintained a near monopoly on broadcast media, giving it an unfair advantage over other political parties and limiting access to information for voters, many of whom rely on television and radio for their news and information. State-owned TVK and privately owned stations controlled by the family or associates of Prime Minister Hun Sen continuously broadcast pro-CPP news and viewpoints while either criticizing or entirely ignoring opposition parties.

The government further restricted media freedom by forcing the closure or sale of remaining independent local news outlets. The Cambodia Daily was forced to shut in September 2017 and The Phnom Penh Post was sold in May 2018 when faced with dubious tax bills alleging that the newspapers owed millions of US dollars to the government. Both newspapers gave priority to investigative reporting and frequently criticized the government.

Radio Free Asia (RFA) shut down operations in the country in September 2017 after facing government harassment. Two former RFA journalists, Uon Chin and Yeang Sothearin, are in arbitrary detention on bogus espionage charges. In August 2017, the government ordered 32 radio frequencies in 20 provinces to stop broadcasting because they aired independent news broadcasts by Voice of America, RFA, and Voice of Democracy.

Self-censorship is also a significant problem for local journalists covering the election. On May 24, 2018, the National Election Committee introduced a code of conduct for the media that includes a prohibition on reporting that leads to “confusion and loss of confidence” in the election, publishing news based on rumors or lack of evidence, and using provocative language that may cause disorder or violence. The code also prohibits the publication of news that affects national security and political, and social stability, or expresses personal opinions or prejudice, and prohibits and interviews at voter registration sites, polling places, and ballot-counting locations.

Politically biased National Election Committee

Cambodia’s National Election Committee has lacked credibility because of political bias since its creation before the 1998 national elections.

Political negotiations between the CPP and CNRP after the 2013 elections resulted in some electoral reform, with two election laws adopted in March 2015: the Law on the Election of Members of the National Assembly (LEMNA) and the Law on the National Election Committee. The reformed election committee had nine members, with four chosen by the CNRP and four by the CPP, and the ninth member independent and non-partisan.

However, the government immediately sidetracked the ninth member. Ny Chakrya, a former senior official of the nongovernmental human rights group ADHOC, by bringing baseless criminal charges against him. Shortly after he started work as deputy secretary-general of the election committee in February 2016, the government filed bribery charges against him and four senior ADHOC officials for what was legitimate human rights work. He was detained in April 2016 and held for 427 days.

After the CNRP was dissolved in November 2017, the four members affiliated with it on the election committee resigned, leaving the body completely controlled by the CPP.

In April 2018, the NEC threatened to prosecute anyone who urged voters to boycott the elections. In June 2018, it sent a message to mobile phone subscribers in Cambodia forbidding “criticizing, attacking, or comparing their party policies to other parties.”

Independent local and international nongovernmental organizations have declared that they will not conduct NEC-accredited election observation out of concerns that this would provide undue legitimacy for the election.

Laws restricting freedom of association and voting rights

In 2017, the government rushed through the National Assembly repressive amendments to the Law on Political Parties, which had never been amended since its adoption in 1997. The amendments empowered authorities to dissolve political parties and to ban party leaders from political activity without due process. This revised law enabled the arbitrary arrest of Kem Sokha, the CNRP leader, without a warrant and despite his parliamentary immunity. He had already faced de facto house arrest in 2016 in another politically motivated case.

He remains in pretrial detention despite deteriorating health while judicial investigators ostensibly examine allegations – based on a videotaped speech to CNRP supporters in Australia – that he is leading a “color revolution” to topple the government with US support.

Later amendments to Cambodia’s election laws allow for redistributing of a dissolved party’s parliamentary seats to other political parties. After the court dissolved the CNRP, its seats were redistributed to several minor parties that had failed to win seats in the 2013 election.

Amendments to articles 34 and 42 of Cambodia’s Constitution, adopted in March, tightened restrictions on voting rights and freedom of association and require every Cambodian citizen to “respect the constitution” and “defend the motherland.” Article 34 was changed to allow new restrictions on the right to vote, while article 42 now empowers the government to take action against political parties if they do not “place the country and nation’s interest first,” an amendment that could be used arbitrarily to target opposition parties.

Partisan campaigning by security force members, civil servants

Senior members of the security forces have endorsed Prime Minister Hun Sen and the CPP at numerous public rallies and other events throughout Cambodia.

Article 9 of the Law on the General Status of Military Personnel of the Royal Cambodian Armed Forces (RCAF) states that “military personnel shall be neutral in their functions and work activities, and the use of functions/titles and the state’s materials for any political activities shall be prohibited.”

The partisanship of the military and police have created an intimidating atmosphere for voters in many parts of the country. Relying on official and semiofficial media reports, Human Rights Watch has extensively documented the systemic and open support of senior and local military and police officers for a CPP election victory, and in particular Hun Sen’s continuation as prime minister.

Those involved include the RCAF supreme commander, Pol Saroeun; the RCAF deputy supreme commander, Kun Kim; the deputy commander in chief of RCAF, Meas Sophea; the acting RCAF supreme commander, Sao Sokha; and Hun Sen’s son, Lt. Gen. Hun Manet. Many of them are members of top ruling party leadership bodies and concurrently heads of its “work teams” assigned to organize and mobilize voting for the party in the provinces.

Opposition leaders and activists told Human Rights Watch that they constantly fear that if Hun Sen and the CPP perceive them as posing an electoral threat, the military and police could be ordered to take action against them, including through arbitrary arrests and violence. “It’s always in the back of our minds,” one opposition candidate told Human Rights Watch.

The list of CPP National Assembly candidates includes active-duty high-ranking military, gendarmerie, and police officers, such as Pol Saroeun, Meas Sophea, and Kun Kim, who have helped maintain Hun Sen’s continued rule since 1985.