On May 12, 2017, US Attorney General Jeff Sessions issued a memorandum ordering US Department of Justice prosecutors to file the harshest possible “readily provable” charges and to refrain from any efforts to avoid the imposition of the harshest possible sentences. This order reversed course for a Justice Department that, in recent years, had moved to scale back excessive sentencing, particularly in drug cases. It also goes against an emerging bipartisan trend towards more proportionate sentencing and alternatives to prison.

Human Rights Watch opposes this policy change, which will result in more disproportionately severe sentences, often for minor offenses, driving up the number of people needlessly incarcerated. It will also further erode the legitimacy of a justice system whose credibility has already been badly undermined by draconian and abusive laws and enforcement strategies. The federal and state governments should instead end over-incarceration, including by eliminating mandatory minimum sentences, allowing more judicial discretion to tailor punishment to the individual circumstances of the case, adjusting sentences so their severity is proportionate to the gravity of the crime, ceasing criminal prosecution of immigration offenses and of drug possession for personal use, and creating non-incarceration strategies to address public safety.

The following are questions and answers about the details of this policy shift and the impact it is likely to have on federal prison populations, drug and crime control, and human rights.

What does Attorney General Sessions’ memorandum on “Department Charging and Sentencing Policy” say?

What were previous administrations’ policies?

What are sentencing guidelines and mandatory minimums?

What have been the effects of the guidelines and mandatory minimum sentences?

Have tough-on-crime policies been effective tools at limiting problematic drug use?

What are the human, financial, and social costs, and racial implications, of excessive sentencing?

What are the human rights concerns raised by Sessions’ change in policy?

***

What does Attorney General Sessions’ memorandum on “Department Charging and Sentencing Policy” say?

The memorandum establishes a new charging and sentencing policy for all federal prosecutors throughout the United States, who are responsible for bringing charges involving federal crimes. The federal system accounts for approximately 13 percent of the US prison population.[1] Sessions has ordered prosecutors to “charge and pursue the most serious, readily provable offense.” He clarifies that the most serious offense, by definition, is the one carrying the most severe punishment under the federal sentencing guidelines, including bringing charges with mandatory minimum sentences.

The directive tells prosecutors that they may not use their discretion to charge a less serious crime, even if they believe, given the circumstances and context of the actual case, that a lesser charge would achieve a more just outcome. Exceptions are to be few and far between, and possible only with the approval of a politically appointed supervisor. A typical example would be the case of a drug courier who was paid a small amount of money to drive a truck loaded with cocaine across state lines. Because sentencing guidelines in drug cases are generally tied to the amount of the narcotics, this driver may face the same severe penalties as the leader of the cartel moving the same amount. Under Sessions’ policy, a front-line prosecutor or assistant US attorney would have to get approval from an appointed US attorney or assistant attorney general to file or pursue a lesser charge.

The directive also tells prosecutors that they must present all facts relevant to the sentencing decision to the judge. This deprives prosecutors of what is often the only practicable way to avoid triggering a harsh sentence that the crime does not warrant. In the case of the truck driver, prior to Sessions’ memo a prosecutor might have refrained from citing an amount of narcotics the driver was transporting in his sentence request so as not to trigger a disproportionate sentence. Sessions’ memorandum deliberately closes off that option. The effect as well as the intent is to promote long sentences and to limit discretion for front-line prosecutors to agree to a lesser amount of prison time. As a large percentage of the crimes this directive applies to are drug crimes, it marks a shift away from the previous administration’s modest easing of the “drug war.”

What were previous administrations’ policies?

In September 2003, then-Attorney General John Ashcroft issued a very similar memorandum directing all federal prosecutors to “charge and pursue the most serious, readily provable offense or offenses that are supported by the facts,” except with approval from politically appointed supervisors under certain circumstances. Ashcroft, like Sessions, emphasized that he intended prosecutors to pursue “the most substantial sentence” under the guidelines, and that the charges should not be dismissed except under narrow circumstances. Ashcroft also ordered his prosecutors to present all facts that might increase a sentence under the guidelines and not to agree to reduced sentences without approval, and only in rare instances.

In the Obama administration, Attorney General Eric Holder issued two directives to federal prosecutors that modified the Ashcroft policy. In May 2010, he wrote that, “the reasoned exercise of prosecutorial discretion is essential to the fair, effective, and even-handed administration of the federal criminal laws.” While he said that prosecutors should charge the most serious offense, decisions should “be made on the merits of each case, taking into account an individualized assessment…” of the specific circumstances of the case. He applied this individualized consideration to decisions concerning plea bargains and advocacy at sentencing. All decisions were to be reviewed by supervisors, though not necessarily by appointed US attorneys.

In 2013, Holder issued a memorandum expanding this policy, particularly as it applied to mandatory minimum sentences and enhancements in drug cases. He stated: “Long sentences for low-level, non-violent drug offenses do not promote public safety, deterrence, and rehabilitation.” He established a set of criteria to define a low-level, non-violent drug offender: 1) the defendant did not use violence or threats, possess a weapon, traffic to minors or cause serious injury; 2) the defendant was not a leader or supervisor within a criminal organization; 3) the defendant did not have significant ties to a gang or cartel; 4) the defendant did not have a significant criminal history. For anyone who met all of these criteria, federal prosecutors were to refrain from alleging the amount of narcotics, therefore avoiding mandatory minimum sentences. Holder gave prosecutors filing enhanced sentences for recidivists similar guidelines. All decisions by front-line prosecutors to refrain from charging the most serious provable offense required review by their supervisors, but not necessarily by the US attorney.

What are sentencing guidelines and mandatory minimums?

In 1984, responding to a belief that federal criminal sentencing was too lenient and too discretionary, leading to great disparities in punishments for the same offenses, the US Congress passed the Sentencing Reform Act. This law created a Sentencing Commission, which established mandatory guidelines that dictated how much prison time a judge must hand out based on rigid factors, including the level of seriousness of the offense and the defendant’s criminal history. The guideline sentence may be raised based on other factors, including causing physical injury, using a weapon, or damaging property; or lowered, for example, if the defendant voluntarily admitted the crime or had acted under duress.

Mandatory minimums set a baseline sentence for a given offense, below which a judge may not go. The Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986 established minimum sentences for drug offenses, generally based on the weight or amount of the narcotics associated with the defendant. Some have criticized the amounts as being chosen arbitrarily. Other laws have added mandatory minimum sentences for different crimes, including weapons offenses. From 1991 to 2011, the number of federal offenses with mandatory minimums doubled.

The guidelines and mandatory minimums have resulted in significant increases in the amount of prison time federal convicts serve. They have also shifted sentencing discretion away from the judge and into the hands of the prosecutor, as the decision of what charges to file usually determines what sentence will result. They severely restrict a judge’s ability to account for extenuating circumstances. The 2006 Supreme Court case United States v. Booker changed the guidelines from being mandatory to advisory, giving judges some more discretion in sentencing, though they generally stick to the guidelines unless prosecutors agree to reductions.

What have been the effects of the guidelines and mandatory minimum sentences?

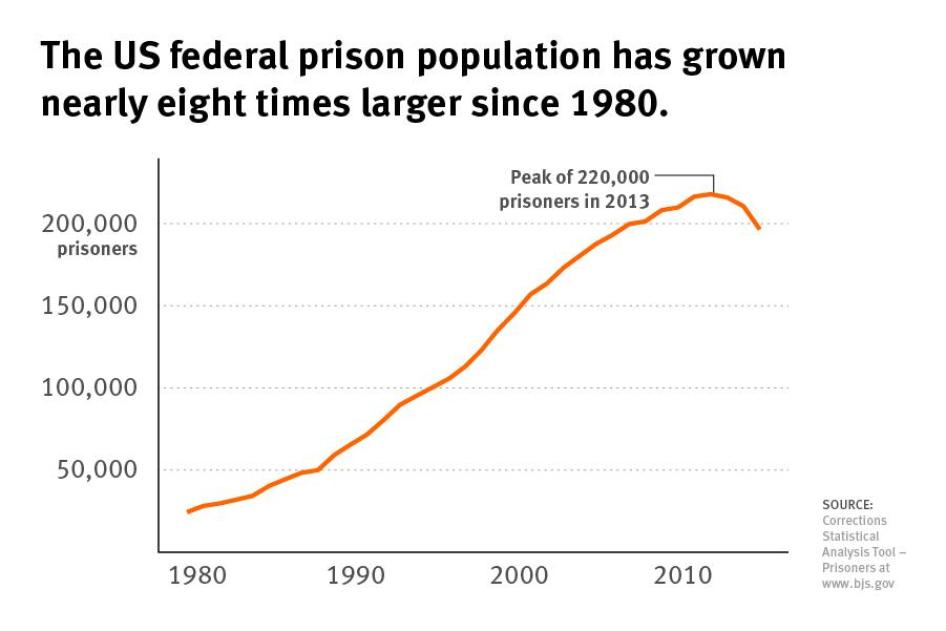

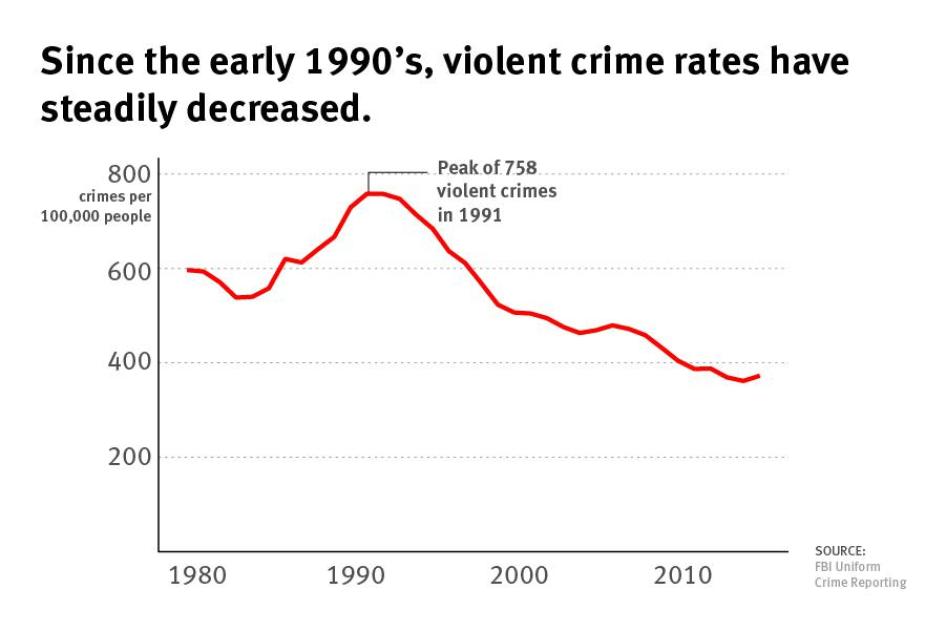

The federal prison population had remained fairly constant from 1940 through 1980. Since then, with the acceleration of the “war on drugs,” a huge increase in prosecutions of immigration-related offenses, mandatory minimum sentences and the guidelines, and the abolition of federal parole, it has grown nearly eight times larger, peaking in 2013 at 220,000 prisoners. This rise of the prison population continued despite the steady decrease in crime rates, including violent crime rates, since the early 1990s.[2]

Drug convictions have gone up considerably. Approximately 50 percent of federal prisoners were sentenced for drug offenses; just under 60 percent of those received mandatory minimum sentences. Fewer than 10 percent of federal prisoners are charged with violent offenses; fewer than 20 percent are charged with weapons offenses. By contrast, only 16 percent of prisoners in state penitentiaries are there on drug charges.[3] The average sentence for the 55,000 federal drug offenders with mandatory minimums is 11 years. For those without mandatory minimums sentences are considerably lower though still high—over 6 years, on average—in part because guideline sentences are set high based on the mandatories. In recent years, immigration cases have added significantly to the federal prison population.

These severe and inflexible sentencing rules and aggressive prosecution of drug and now immigration crimes have led to the massive increase in federal prisoners, many most likely serving sentences that are substantially disproportionate to the offense involved. Human Rights Watch has documented how these sentencing rules pressure defendants to plead guilty, noting that those who were convicted at trial receive sentences on average 11 years longer than those who plead. The bipartisan Charles Colson Task Force on Federal Corrections has concluded that, “terms of incarceration in federal prison are often substantially greater than necessary to meet the goals of sentencing, and mandatory minimum penalties have been a primary contributor to this imbalance.”

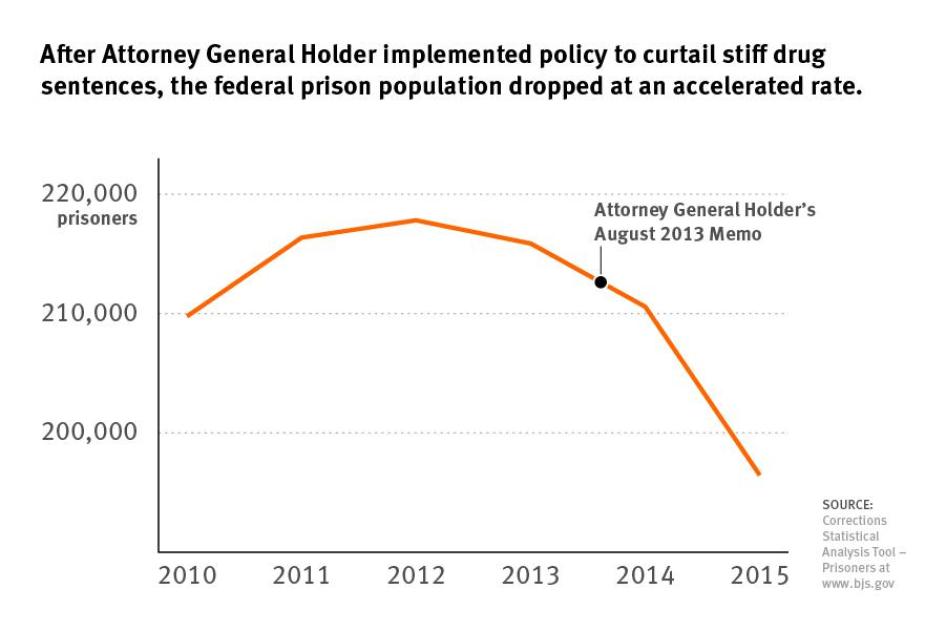

Federal prison populations had begun to drop after their peak in 2012. After Holder implemented his policy, that drop accelerated, lowering from 218,000 to 197,000 by 2015.

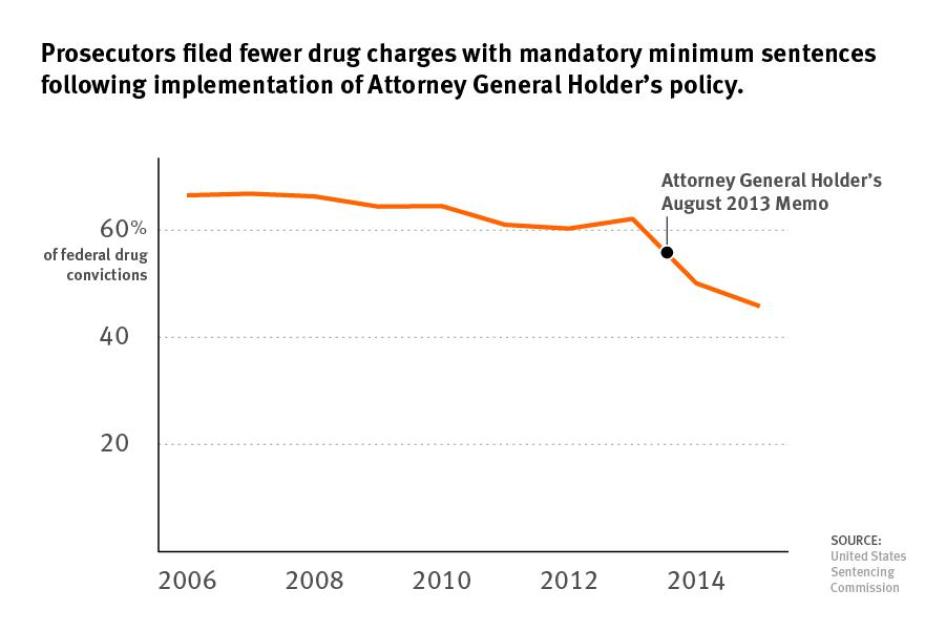

Prosecutors filed drug charges with mandatory minimums less frequently. In 2006, approximately two of every three drug cases filed carried a mandatory minimum; in 2015, that figure was 46 percent.

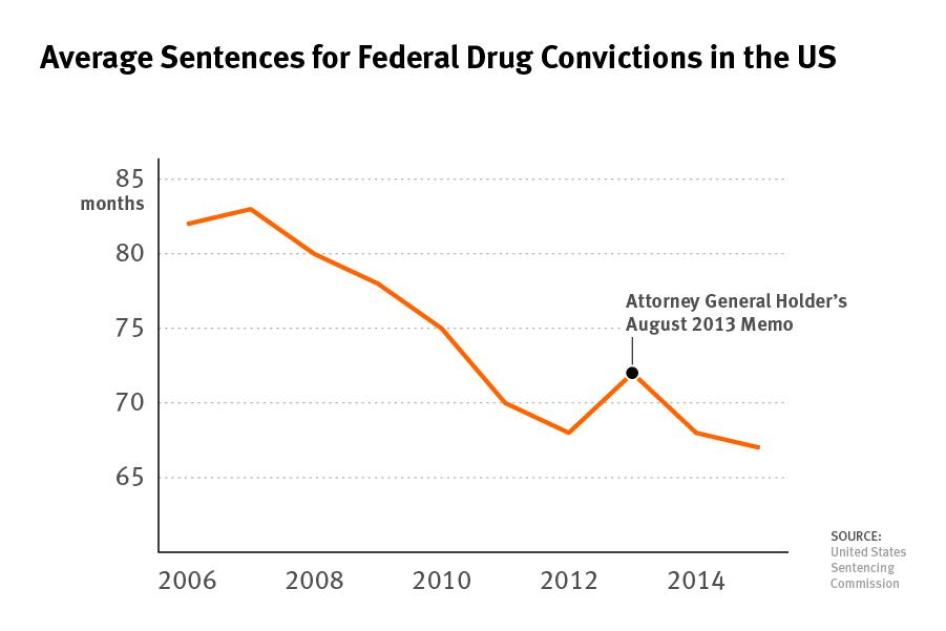

In 2015, federal prosecutors filed almost 5,000 fewer drug cases than they had in 2012, a 20 percent reduction and the lowest number in the last decade. Average sentences for drug offenses dropped to 67 months following implementation of the policy, though they had been steadily dropping from a high of 83 months in 2007.

While it is not certain how much the change in policy led to these reductions, it is likely to have made some significant difference, particularly with the reduced numbers of people charged with mandatory minimums.

Long, harsh and inflexible sentences for drug offenders, including mandatory minimums, have been ineffective in reducing drug use and trafficking, while they have contributed to over-incarceration. This has been costly to taxpayers, disruptive to families and communities, and devastating to individuals, many of whom are sentenced to long prison terms for non-violent, relatively minor crimes. The reduction in the harshness of sentencing under the Holder memo was a good start to efforts to reduce the harm and costs of over-incarceration at the federal level.

In a 2014 letter to his colleagues in Congress successfully urging them to defeat the Smarter Sentencing Act, which would have significantly cut many mandatory minimum sentences for drug crimes, Sessions wrote: “The notion that drug traffickers are non-violent is simply incorrect,” and “lower mandatory minimum sentences mean increased crime and more victims.” He said that to trigger a 10-year mandatory minimum a person must possess at least one kilogram of heroin or five kilograms of cocaine, contending that these sentences only impact major traffickers.

But in making this point, Sessions neglected the fact that many of those caught with these relatively large quantities of drugs are not leaders of cartels or even serious criminals, but instead are essentially laborers, contracting to transport or sell the drugs and not involved in violent enforcement of drug sales agreements or reaping the major profits. The United States Sentencing Commission recently reported to Congress that 40 percent of federal drug defendants were couriers or street dealers. The Sentencing Commission also found that approximately 84 percent had no weapon, undermining Sessions’ claim of the inherent violence of all drug defendants. The Colson Task Force found that among drug prisoners, 45 percent had a minimal criminal history, 25 percent had none, 80 percent had no serious violent history, and over 50 percent had no violent history at all. Only 14 percent were found to be supervisors or leaders in the drug enterprise.[4]

Mandatory minimums and strict sentencing guidelines do not allow judges to make crucial distinctions between low level “mules” or couriers and street dealers supporting their own habits or pressured by economic circumstances on the one hand as opposed to the leaders of drug trafficking networks on the other. Long sentences for low level participants, based strictly on the amount they are carrying, are an ineffective way to combat the drug trade as these individuals are easily replaced if they are put in prison, given the financial incentives.

The Colson Task Force also noted that drug offenders with weapons-use enhancements were not necessarily dangerous or violent. The sentences of many are enhanced—that is, lengthened—because they had weapons in their home or car, but were not actually using the weapon in their narcotics transactions. Seventy-two percent of defendants with weapons enhancements had no serious history of violence and almost 50 percent had no history of violence at all. Considering the broad differences in public safety threats that these defendants pose, strictly limiting judicial sentencing discretion will result in unfair and disproportionate sentences. Prosecutors have historically used these enhancements as a threat to leverage guilty pleas.

Sessions contends that any lessening of criminal sentencing, including for drug offenders, would allow criminals to commit more crimes and would remove a valuable deterrent. The National Research Council of the National Academy of Sciences “reviewed the research literature on the deterrent effect of [long sentences, including mandatory minimums] and concluded that the evidence is insufficient to justify the conclusion that these harsher punishments yield measurable public safety benefits.”[5] The council found weak evidence that increased incarceration reduces crime, and that any possible reductions may be seem paltry when weighed against the considerable harm of mass incarceration.[6] Many contend that prison sentences are more likely to cause crime than to reduce it, as prisoners learn to become criminals while in prison and return home to unstable family situations with limited options for employment.

The Colson Task Force concluded that “there is broad, bipartisan agreement that the costs of incarceration have far outweighed the benefits…. Indeed, a growing body of evidence suggests that the over-reliance on incarceration may in fact undermine efforts to keep the public safe.”

Have tough-on-crime policies been effective tools at limiting problematic drug use?

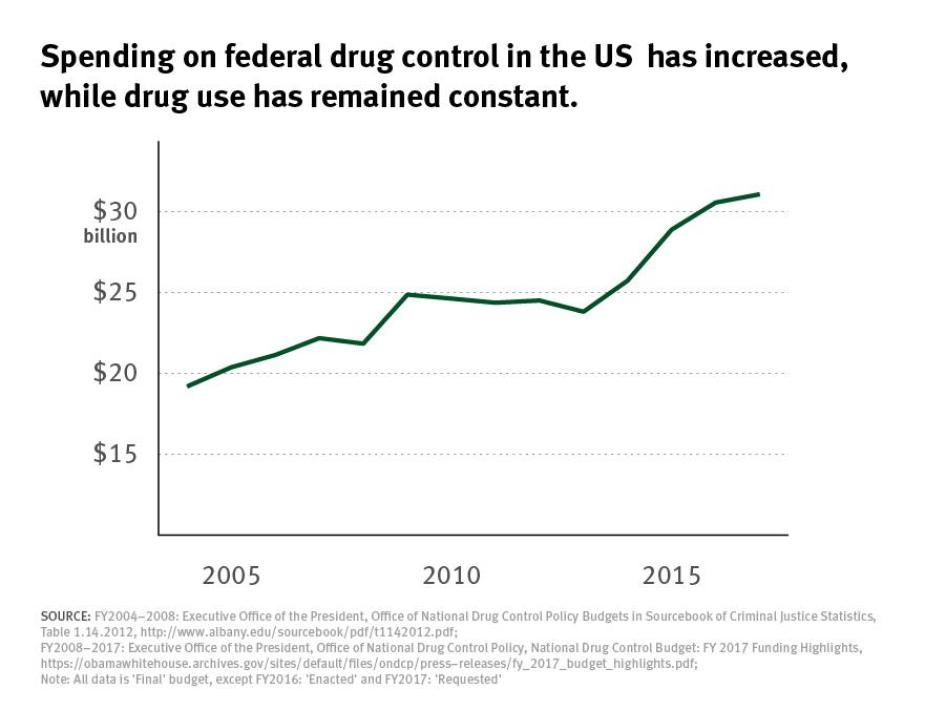

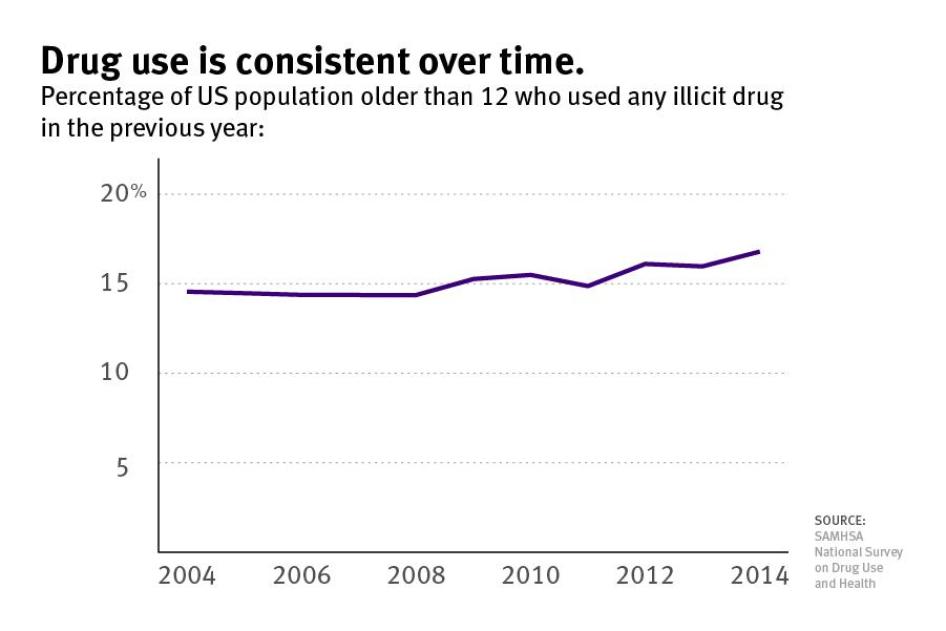

No. Rates of drug use fluctuate, but they have not declined significantly since the “war on drugs” was declared more than four decades ago. A 50-state study has found that higher rates of drug imprisonment have no effect on rates of drug use or numbers of overdose deaths. Federal drug control spending has increased steadily throughout the prosecution of the drug war, while drug use has remained fairly constant. Data since 2004 shows increased spending, over $343 billion total, while drug usage has increased slightly from 2004 through 2014. When controlling for inflation and population growth, federal drug control spending, including for domestic law enforcement, interdiction and international enforcement, as well as prevention and treatment programs, has grown from $83 per person in 2004 to $95 per person in 2017.

Meanwhile, prohibition and criminalization have enhanced the profitability of the drug trade, fueling the operations of gangs and organized criminal groups that often victimize people in the poorest communities and have had devastating effects on human rights and the rule of law in many countries around the world.

What are the human, financial, and social costs, and racial implications, of excessive sentencing?

Adjusting for inflation, the federal Bureau of Prisons’ budget has gone from $950 million to $7.5 billion in the past 35 years. The Colson Task Force projected that restricting mandatory minimum sentences to only the most serious offenders would save close to $2.2 billion by 2024.

Along with costs to taxpayers for enforcement, prosecution and lengthy incarceration of drug offenders, there is the devastating cost to the individuals and their families and communities.[7] Prisoners are separated from their families for years, causing their children to grow up with a limited parental relationship. Health care, particularly, for mental health, in prisons is often inadequate, while incarceration itself can exacerbate existing health conditions. Prisoners lose homes, jobs, and careers, often returning from prison with limited work prospects, and sometimes facing homelessness. Once released, former prisoners are excluded from various benefits, including housing and food assistance, that they may desperately need as they struggle with re-entry.

There are also opportunity costs, as money spent on incarceration could otherwise be invested in improved education, health care, housing and other projects that might improve communities and lower crime rates.

The change will also have racial implications. There is a significant racial component to the prosecution of the drug war—something Human Rights Watch research has confirmed repeatedly. Black and white people use drugs at comparable rates, but Black people are much more likely to be arrested for drug use; the limited available data suggests the same may be true for drug sales. Though white people make up 61 percent of the US population, they only account for about 25 percent of federal drug prosecutions.

What are the human rights concerns raised by Sessions’ change in policy?

Government’s extraordinary power to criminalize and punish should be used sparingly, and with due considerations for the principles of proportionality and respect for human dignity that human rights law requires. Punishment should be proportionate to the offense and the individual’s blameworthiness and no greater than necessary. To be consistent with international human rights, punishment must be limited to what is necessary to accomplish the legitimate purposes of incarceration.

Mandatory minimums and harsh sentencing guidelines are often disproportionate to the individual’s actual blameworthiness and prevent judges from tailoring punishment to fit the circumstances of the individual and the crime. The punishments themselves are frequently far more severe than the crime merits, especially for low-level offenders facing mandatory minimums.

More broadly, Sessions’ guidance appears to be part of a broader effort by the attorney general to recommit and enhance the “war on drugs,” which, with its reliance on criminalization, prosecution and incarceration, has carried a devastating human toll and helped perpetuate serious violations of human rights in the US as well as abroad, while doing little to change rates of global drug production or overall drug use in the US.

The bipartisan Colson Task Force called for repeal of mandatory minimum sentences, including making the repeal retroactive for those previously sentenced and providing incentives for using alternatives to prison. No proposed legislation goes this far.

However, several bipartisan bills in recent years have attempted to ease the impact of these sentences and give judges more discretion with non-violent, lower level offenders. Senators Rand Paul (R-KY) and Patrick Leahy (D-VT) introduced the Justice Safety Valve Act of 2015, which would have allowed judges to sentence below any mandatory minimum in all future cases, if the defendant met the criteria under 18 USC 3553 (little criminal history, no violence or weapons, no injury from the crime, no supervisory role and cooperation with the government), and the judge found such a sentence protected the public, deterred future crime, reflected the seriousness of the offense and provided for the needs of the defendant. This bill did not pass.

Other proposed bills have been the Smarter Sentencing Act, which, among other things, would have reduced mandatory minimum sentences for drug offenses and reduced sentences for those who only transported or stored drugs or money; the Sentencing Reform and Corrections Act, which would have reduced certain mandatory drug and weapons sentences and expanded “safety valve” provisions, though it also would have created new mandatory minimum sentences; the SAFE Justice Act, which would have limited application of mandatory minimum drug sentences to leaders of the criminal enterprise, expanded existing and created new “safety valves” for drug and gun sentences, and taken other significant steps to reduce mandatory minimum sentences. Each of these bills had bipartisan sponsorship; none of them passed. As a senator, Sessions actively opposed them.

However, following Sessions’ sentencing order, Senators Leahy, Paul and Merkley re-introduced the Justice Safety Valve Act and Representatives Thomas Massie (R-KY) and Bobby Scott (D-VA) introduced a companion bill.

Meanwhile, Senator John Cornyn and Congressman Ted Poe have introduced the “Back the Blue Act,” which makes a federal crime out of any assault on a police officer and imposes mandatory minimum sentences for those offenses. Senator Cornyn is reportedly drafting an omnibus crime bill that will incorporate those mandatory sentences from the Back the Blue Act, and increase sentences for a variety of immigration offenses. Senators Dianne Feinstein and Chuck Grassley are proposing a bill targeting synthetic opioids, that will impose severe sentences.

Sessions should rescind this policy statement and return to the more flexible approach of his predecessor. He should continue the de-escalation of the “war on drugs” started under the Obama administration and supported by many prominent conservatives. He should seek out alternatives to incarceration for low-level offenders.

It is highly unlikely that Sessions will reverse course. Therefore, Congress should act. It should reject “Back the Blue,” the Feinstein/Grassley bill and any other laws increasing sentence severity or expanding the use of mandatory minimums. Congress should, at the very least, pass the bi-partisan “Justice Safety Valve Act.”

In the longer term, lawmakers should take steps to ensure that criminal laws permit judges to impose fair and proportionate sentences. They should eliminate mandatory minimum sentences and rigid sentencing guidelines that prevent judges from considering mitigating circumstances relevant to sentencing decisions. Federal and state lawmakers should decriminalize drug use and possession for personal use. They should reduce or eliminate criminal sanctions for immigration offenders, especially those who have done nothing more than enter the country illegally.

In recent years, policymakers from a variety of perspectives have come to realize that the US incarcerates far too many people, needlessly harming those individuals, their families and their communities, and costing taxpayers greatly, with little impact on public safety. The US government should return to that promising consensus and reverse Sessions’ misguided policy.

[1] This percentage does not take into account the more than 11 million local jail admissions per year.

[2] Incarceration rates have some impact on lowering crime, though studies have shown that, as incarceration rates went up in the 1990s and 2000s and crime rates went down, the increased incarceration rates had less and less effect. Many other factors have also been shown to shape crime rates, including policing, economic factors (e.g. unemployment rates and wage levels), education factors, environmental factors (e.g. lead exposure), demographic factors, etc. Little is known about how all of these factors, along with incarceration, influenced crime in the past and will influence it moving forward. In considering criminal justice policies, any crime reduction value of incarceration, speculative as it is, must also be weighed against the substantial and known societal costs of additional incarceration. Policymaking must also be limited by the rights of defendants and prisoners against disproportionate punishment.

[3] These rates include information about the lead charge and do not provide insight into the effect of previous criminal history, including drug offenses, on sentencing. Though 50 percent of federal prisoners were sentenced on a drug offense, drug offenders make up 32 percent of new prison admissions.

[4] “Serious violent history” is defined as something more dangerous than a simple assault or crime that does not typically lead to serious injury.

[5] National Research Council, The Growth of Incarceration in the United States (Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2014, p. 347

[6] National Research Council, The Growth of Incarceration in the United States (Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2014, p. 340

[7] National Research Council, The Growth of Incarceration in the United States (Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2014, p. 339