We arrived at the institution for people with disabilities on a day in November 2016. The door had heavy locks. Once inside, in the back of a room full of beds, we saw a woman waiving us closer. She had cerebral palsy and could not communicate verbally, but she was radiant and smiling, apparently happy to meet someone from the outside world. The woman, Luciene, handed me a book titled Scent of a Lifetime.

The book was her own story of spending 40 years in an institution. It was a story of expectations and emotions, of intense joy and deep reflections. Literally the scent of a lifetime. Luciene, the daughter of a domestic worker, was left in the care of a neighbor when she was 5 while her mother worked. The neighbor often got angry because Luciene couldn’t communicate when she had to use the toilet and regularly wet her clothes. When Luciene was 9, her mother took her to an institution.

Luciene’s case is not unique. According to 2017 official data from the social assistance service, 5,078 children and 5,037 adults with disabilities were living in institutions, not including older people that might also have disabilities and who live in nursing homes.

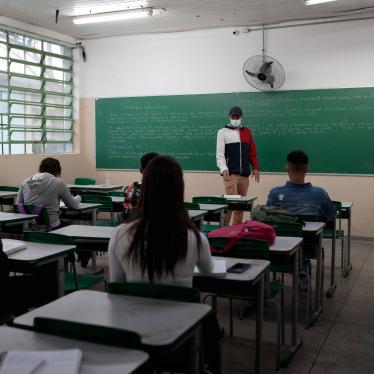

“Why should I have to live in an institution?” “Why can’t I live with my mother who is the most precious being for me?” “Why can’t I go to a school and study like other children?” She asked herself during the first months living there. Later, she was able to go to a school next to the institution. “What a wonderful sensation to be able to learn,” she wrote.

She met other children, some of them with disabilities. But friends disappeared, transferred to other institutions. It was as if they had suddenly passed away. When she was sad, she would remind herself that she was lucky because some children in the institution were imprisoned in their beds, not allowed to go to school.

Going to school gave her, she said, the feeling of being normal. But one day, without explanation, the institution staff told her that she would no longer attend school. They tried to comfort her, telling her that she could visit her friends. But no one would take her to the school for the promised visits. Institutions can create the feeling of not “being normal” -- the social construction of dependency.

At one point, with the help of her mother’s friends, Luciene was able to move back with her mother. That was a period of great joy for them, but it didn’t last long. When Luciene’s mother turned 82, she was no longer able to support her daughter. Returning to the institution was the only option. There were no community agencies or services to support Luciene to live independently.

My recent research in Brazil found that institution staff and managers aren’t to blame. The problem is a broken system that doesn’t allow people with disabilities to live independently, in the community with opportunities for education, employment and health care equal to everyone else. Thousands end up like Luciene, stuck in institutions, often for their entire lives.

Most of these locked institutions, known as “homes” or shelters for people with disabilities house 32 to 50 people in wards crammed with beds or cribs with high bars. Some people were tied to these bars. They don’t have the look of a “home,” despite the name at the entrance.

No one should be forced into a particular living arrangement. People with disabilities should not be locked away from society. The right to live independently is the path to realize many other fundamental rights: to privacy, to marry, to have a family, to participate in cultural, and political life.

All levels of the Brazil government should develop comprehensive policies to phase out institutions and create conditions for people with disabilities to choose where and with whom to live. The governments should develop in-home residential and other community support services, including personal assistance. Authorities should also strengthen and expand foster care and adoption for children with disabilities. Involvement by nongovernmental groups, including current institution managers and organizations of people with disabilities, is essential.

Luciene’s story shows us that Brazil has a structural problem that hinders the right of children to live with a family and of people with disabilities to live in the community. Brazil needs national policies that ensure people with disabilities’ right to have a home.