(New York) – It is more relevant than ever on the 25th anniversary of the genocide in Rwanda to understand the importance of international action to prevent large-scale atrocities and the need for justice in their aftermath.

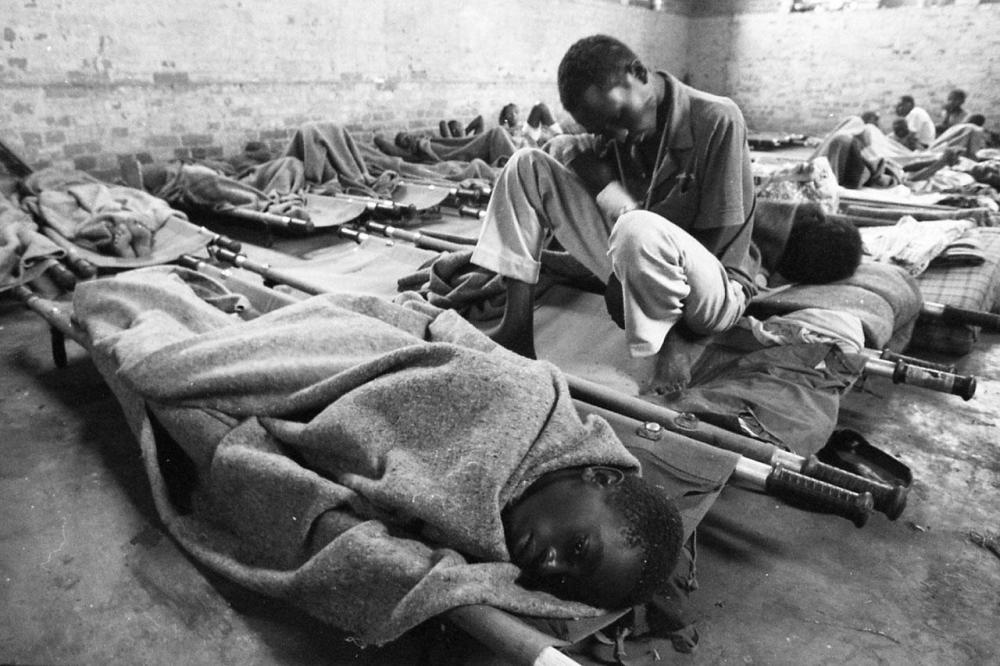

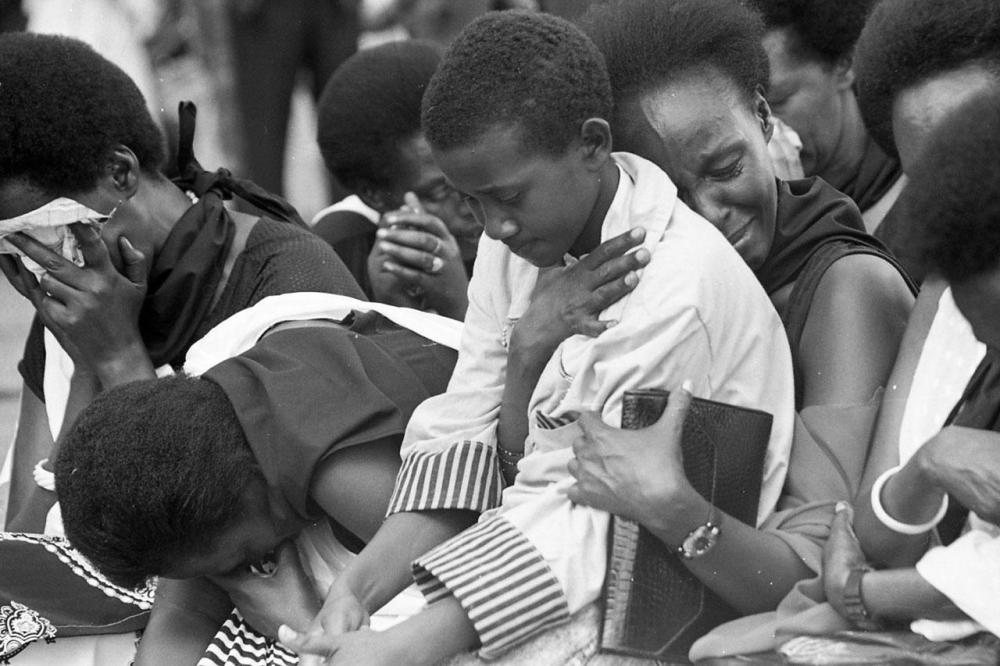

Human Rights Watch expressed its solidarity with the victims and survivors of the genocide, one of the most terrifying episodes of ethnic violence in modern history, which was carried out at breakneck speed.

“Rwanda and the wider region are still grappling with consequences of the genocide,” said Kenneth Roth, executive director of Human Rights Watch. “Twenty-five years on, the victims and survivors should remain the center of everyone’s thoughts, but we should also take stock of progress and the need to ensure accountability for all those who directed these horrific acts.”

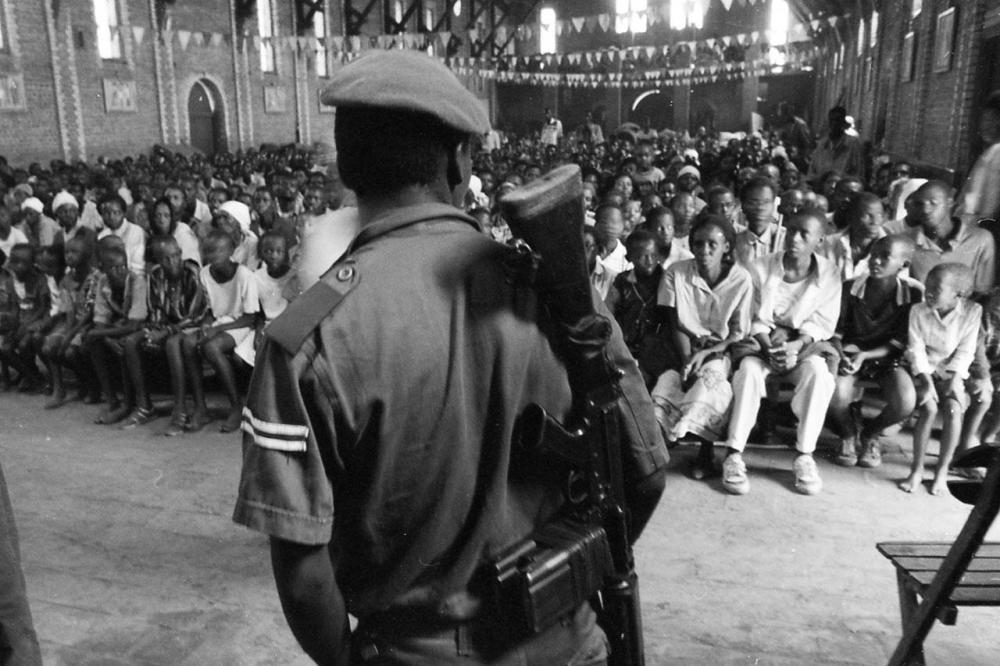

On April 6, 1994, a plane carrying the Rwandan President Juvénal Habyarimana and the Burundian President Cyprien Ntaryamira was shot down over the Rwandan capital, Kigali. The crash triggered the start of three months of ethnic killings across Rwanda on an unprecedented scale.

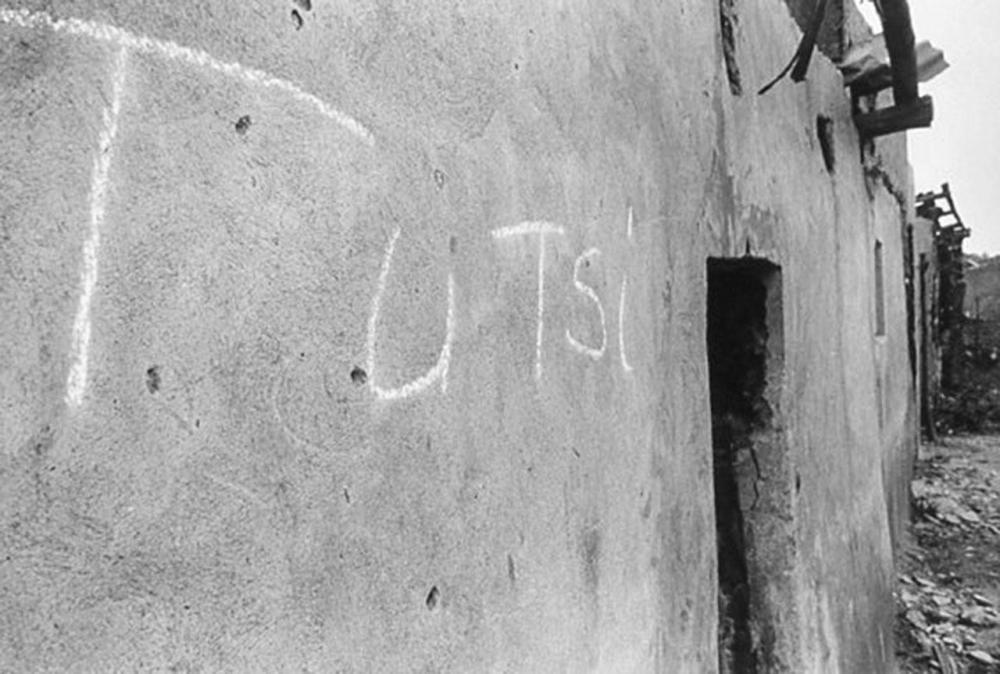

Hutu political and military extremists orchestrated the killing of approximately three quarters of Rwanda’s Tutsi population, leaving more than half a million people dead. Many Hutu who attempted to hide or defend Tutsi and those who opposed the genocide were also killed.

In mid-July 1994, the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), a predominantly Tutsi rebel group based in Uganda that had been fighting to overthrow the Rwandan government since 1990, took over the country and ended the genocide. Its troops killed thousands of predominantly Hutu civilians, though the scale and nature of these killings were not comparable to the genocide.

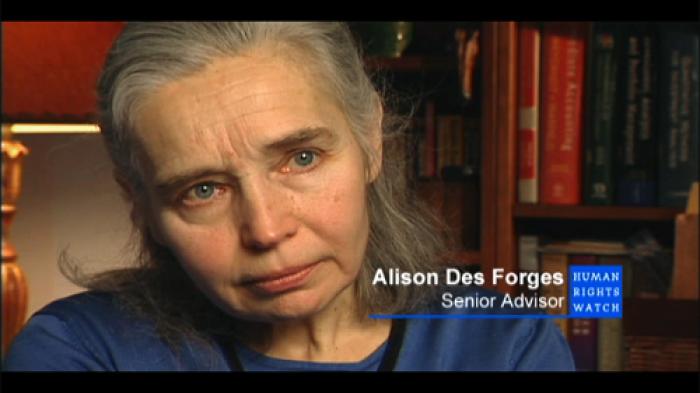

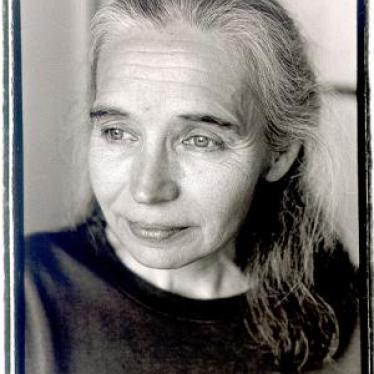

Human Rights Watch documented the genocide and the RPF’s 1994 crimes in detail. Alison Des Forges, senior adviser to the Human Rights Watch Africa division for almost two decades, published the authoritative account of the Rwandan genocide, “Leave None to Tell the Story,” and documented the international community’s indifference and failure to act.

“When international leaders did finally voice disapproval, the genocidal authorities listened well enough to change their tactics although not their ultimate goal,” Des Forges said in her account. “Far from cause for satisfaction, this small success only underscores the tragedy: if timid protests produced this result in late April, what might have been the result in mid-April had all the world cried ‘Never again.’”

This realization that the world should not stand by while mass atrocities occur within a sovereign state gave birth to the concept of “responsibility to protect,” a global political commitment to prevent genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing, and crimes against humanity.

After coming to power, the RPF faced the long and arduous process of rebuilding a country that had been almost entirely destroyed and delivering justice to the victims and their families.

Twenty-five years on, a significant number of people responsible for the genocide, including former high-level government officials and other key figures, have been brought to justice.

The United Nations Security Council created the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda in 1994 in response to the genocide. The tribunal indicted 93 people, convicted and sentenced 61, and acquitted 14. It made significant contributions to establishing the truth about the organization of the genocide and providing justice to victims. Des Forges appeared as an expert witness in 11 genocide trials at the tribunal.

However, the ICTR only covered a small number of cases and was unwilling to prosecute war crimes and crimes against humanity committed by the RPF. The tribunal formally closed on December 31, 2015.

“The tribunal was an extraordinary step in the international response to serious and widespread human rights violations,” Roth said. “But its legacy was undermined by its failure to prosecute RPF abuses.”

The Rwandan justice system also tried a large number of genocide suspects, both in conventional domestic courts and in local, community-based gacaca courts. The standards of these trials have varied enormously and political interference and pressure resulted in some unfair trials. Other cases have shown greater respect for due process. The gacaca trials ended in 2012.

As it wound down its work between 2011 and 2015, the ICTR transferred several genocide cases to Rwandan courts. To provide for the transfer of those cases, as well as extraditions of genocide suspects from other countries, the Rwandan government undertook reforms to the justice system aimed at meeting international fair trial standards. But the technical and formal improvements in laws and administrative structure have not been matched by gains in judicial independence and respect for the right to a fair trial.

Human Rights Watch has observed trials in which charges of genocide ideology and inciting insurrection were used to prosecute prominent government critics. Fair trial standards were flouted in many of these sensitive political cases. Despite these concerns, a growing number of countries have extradited suspects to stand trial for genocide-related charges in Rwanda.

National authorities in some of the countries where Rwandan genocide suspects are living, and in some cases acquired citizenship, have conducted investigations that have led to a number of trials before their domestic courts. The principle of “universal jurisdiction” allows national prosecutors to pursue people believed to be responsible for certain grave international crimes such as torture, war crimes, and crimes against humanity, even though they were committed elsewhere and neither the accused nor the victims are nationals of the country. Trials of Rwandan genocide suspects have taken place in countries including Belgium, Canada, Finland, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, and Switzerland.

“An enduring lesson from the genocide is that impunity drives atrocities,” Roth said. “Despite the passage of time, victims deserve to see all those responsible for genocide and other parallel crimes arrested and prosecuted in fair and credible trials.”

Gacaca Courts

Rwanda's community-based gacaca courts have a mixed legacy. While they rapidly processed tens of thousands of cases in a way that was broadly accepted by the population, they also failed to provide credible decisions and justice in a number of cases.

The population elected judges without prior legal training. They tried cases in front of community members, who were expected to speak out about what they knew regarding the defendants’ actions during the genocide. A gacaca pilot phase began in 2002, but it was not until 2005 that gacaca courts began functioning across the country. They then processed almost two million cases before closing in June 2012.

Some welcomed the swift processing of a huge number of cases, the extensive involvement of local communities, and the opportunity for some genocide survivors to better understand what had happened to their relatives. Many hearings resulted in unfair trials, though. The accused had limited ability to effectively defend themselves; there were numerous instances of intimidation and corruption of defense witnesses, judges, and other parties; and there was flawed decision-making, due to inadequate training for lay judges for complex cases, leading to allegations of miscarriages of justice.

The government’s decision to transfer genocide-related rape cases to the gacaca courts in May 2008 was problematic for the delivery of justice to genocide victims.

Those responsible for the genocide employed sexual violence as a brutally effective tool to humiliate and subjugate Tutsi and politically moderate Hutu women and girls. Grieving for lost family members and suffering physical and psychological consequences of the violence, women and girls who were victims of sexual violence are among the most devastated and disadvantaged of genocide survivors. The decision to transfer rape cases to closed-door proceedings within gacaca courts presented new challenges for the delivery of justice. Victims’ privacy risked being compromised as communities would become aware of cases, although not the details, and carrying out trials behind closed doors raised concerns because of the nature of gacaca courts, which were designed to rely on community participation.

The International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda’s Legacy

The ICTR was expected to try mostly high-level suspects and those who played a leading role in the genocide. It tried and convicted several prominent figures, including former Prime Minister Jean Kambanda; the former army chief of staff, Gen. Augustin Bizimungu; and the former Defense Ministry chief of staff, Col. Théoneste Bagosora.

It achieved important milestones and established jurisprudence in international criminal law. It was the first international tribunal to convict a woman of genocide crimes, including rape, when it found Pauline Nyiramasuhuko, Rwanda’s former minister for family and women’s affairs, guilty for her role in planning and ordering others to carry out these crimes during the genocide. It also became the first international court since the 1946 Nuremberg tribunal to convict media executives for crimes of genocide.

However, the tribunal had inherent limitations and attracted criticism, particularly from Rwandans. At its closing event on December 1, 2015, the Rwandan Justice Minister, Johnston Busingye, reiterated the government’s criticisms of the lack of reparations for victims and the tribunal’s location outside Rwanda, and complained that genocide convicts were allowed to speak to the media. Human Rights Watch and other rights groups also criticized the relatively small number of cases the tribunal handled, its high operating cost, bureaucratic processes, and the length of time that trials took, as well as its failure to prosecute RPF crimes.

Human Rights Watch documented major legal reforms in Rwanda during the years that the ICTR was in operation, but having observed trials and conducted research in Rwanda, remained concerned that the justice system lacked sufficient guarantees of independence to guarantee fair trials in all cases the tribunal returned to Rwanda. Although Human Rights Watch and other organizations brought these concerns to the tribunal’s attention, the tribunal ultimately ruled that it was safe to transfer cases to the Rwandan courts after Rwanda responded to the tribunal’s earlier concerns with legislative reforms. Following the first transfer of an ICTR case, a number of other countries also extradited suspects to face trials in Rwanda.

Reforming Rwanda’s Judiciary

New Chamber to Try International Crimes

Before the ICTR closed, Rwanda’s government established the Specialized Chamber hearing International Crimes and Transnational Crimes (Chamber for International Crimes) within the High Court in 2012. The specialized chamber has jurisdiction to try cases transferred to Rwanda from the ICTR, the Residual Mechanism for International Criminal Tribunals, or the courts of other countries. The chamber was created after countries including Canada, Norway, and the Netherlands agreed to extradite genocide suspects to Rwanda.

The Chamber for International Crimes, previously hosted at the High Court in Kigali, recently moved to a new complex in Nyanza, the administrative capital of Rwanda’s Southern Province. Chief Justice Sam Rugege told the media at the inauguration ceremony in June 2018 that: “The facility offers modern court facilities that meet international standards. It will improve the national capacity to efficiently and fairly try the Genocide cases referred to Rwanda by the ICTR and our jurisdictions.”

In December, Rwanda’s prosecutor general, Jean Bosco Mutangana, told the media that Rwanda has issued about 1,000 indictments since 2008 for Rwandan genocide suspects living in other countries. At least 19 genocide fugitives have been extradited to face trial in Rwanda.

Genocide Ideology and Legal Reforms in Rwanda

The Rwandan authorities have improved the delivery of justice in the last 25 years, a noteworthy achievement given the challenges they faced after the genocide. But while the laws have changed considerably, the underlying politicization of justice remains, hindering the full realization of the reforms.

Rwanda has passed a number of laws that may have been intended to prevent and punish hate speech of the kind that led to the 1994 genocide, but they have restricted free speech and imposed strict limits on how people can talk about the genocide and other events of 1994. Accusations and charges of genocide ideology have been used to silence prominent critics of the government.

Rwandan law defines genocide ideology as a public act that manifests an ideology that supports or advocates for destroying – in whole or in part – a national, ethnic, racial, or religious group.

A 2013 revised version of the law defined the offense more precisely and required evidence of the intent behind the crime, reducing the scope for abusive prosecutions. But the law adopted in 2018 removed language requiring evidence of a “deliberate” act. “Affirm[ing] that there was a double genocide,” which could be interpreted to refer to crimes committed by the RPF, and “providing wrong statistics about victims of the genocide” are now punishable by up to seven years in prison.

Fair Trial Standards and Transfer of the ICTR’s Remaining Cases to Rwanda

To obtain the transfer of cases from the ICTR and extraditions of genocide suspects from elsewhere, the Rwandan government undertook legislative reforms aimed at meeting international fair trial standards. Some have been important and positive, including abolition of the death penalty in 2007 and the creation of a witness protection unit.

Nevertheless, judges at the tribunal turned down several earlier requests by the prosecutor to transfer cases to Rwanda, notably in 2008, as they did not consider that the Rwandan judiciary could guarantee a fair trial. In response, the Rwandan government introduced additional reforms, which eventually paved the way for the tribunal to transfer cases to Rwanda for domestic prosecution.

Since 2011, the tribunal has transferred several genocide cases to the Rwandan courts. The first was Jean Bosco Uwinkindi, the former head of a Pentecostal church outside of Kigali, who was sent to Rwanda in April 2012. In December 2015, he was sentenced to life in prison. He has attempted to get the transfer decision reversed, contending that his right to a fair trial was violated in Rwanda.

The second case to be transferred and stand trial in Rwanda was Bernard Munyagishari, who was transferred in July 2013, and was convicted of crimes of genocide and crimes against humanity in April 2017. A third, Ladislas Ntaganzwa was arrested in the Democratic Republic of Congo on December 9, 2015, and extradited to Rwanda after the ICTR closed down. He was accused of personally leading a group that killed over 20,000 Tutsi. His trial began at the Chamber for International Crimes in 2017.

The tribunal also transferred two cases to France: French courts dismissed Wenceslas Munyeshyaka’s case in October 2015, while Laurent Bucyibaruta’s trial was confirmed in December 2018.

When the ICTR closed, the International Residual Mechanism for Criminal Tribunals (IRMCT), created in 2010, was tasked with arresting and prosecuting the nine remaining tribunal-indicted fugitives, eight of whom remain at large. It retains jurisdiction over Augustin Bizimana, Félicien Kabuga, and Protais Mpiranya, while the six remaining cases were referred to Rwandan authorities. Five of them – Fulgence Kayishema, Charles Sikubwabo, Aloys Ndimbati, Ryandikayo, and Phénéas Munyarugarama – remain fugitives today, while Ntaganzwa is on trial in Rwanda.

In its November 2018 monitoring report, the IRMCT reported that Ntaganzwa had told the court he was held in solitary confinement for 25 days, and that prison authorities had harassed him, threatened to beat him up, and intimidated him for breaching prison regulations after he was found to have a mobile phone. In a meeting with Ntazganzwa in December, he told the IRMCT’s monitors that his defense lawyers had not been allowed to see him during his solitary confinement, and that the authorities had confiscated his laptop for a day, and that he was concerned they had gone through his defense documents.

Trials in Rwanda and Abroad

Trials in Rwanda

Many Rwandans fled their country during and after the genocide in 1994 and sought asylum in Africa, Europe, and North America. Among those claiming to be refugees were some suspected of participating in the genocide.

Until the first ICTR transfer decision, most countries denied Rwanda’s extradition requests. Under international human rights law, the sending country could be held responsible for foreseeable human rights violations of the suspect in Rwanda.

A European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) ruling in October 2011 that it was safe to extradite Sylvère Ahorugeze, a Rwandan genocide suspect arrested in Sweden, reinforced governments seeking to extradite suspects to face trial in Rwanda. Prosecutors and judges in extradition cases in various countries cited the tribunal and European court decisions as precedents when arguing for extradition.

The Rwandan government has requested extradition treaties with dozens of countries in an attempt to try remaining genocide suspects in Rwanda. In 2018, it ratified treaties with Ethiopia, Malawi, and Zambia. Soon after the extradition treaty was ratified, Vincent Murekezi was extradited from Malawi to Rwanda, on January 28, 2019. He was convicted in Malawi of fraud-related offenses and transferred to Rwanda “courtesy of a prisoner exchange agreement.” According to the Rwanda Correctional Service, a gacaca court had previously convicted him in absentia and sentenced him to life in prison for participating in the genocide, primarily in the Huye District.

Other African countries with current extradition agreements with Rwanda on international crimes include the Republic of Congo, Tanzania, Uganda, and – in the context of the International Conference of the Great Lakes Region protocols – Burundi and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Jean Paul Birindabagabo, also known as Pastor Daniel Bagabo, was deported from Uganda to Rwanda in January 2015 to face genocide-related charges. Uganda extradited at least two other genocide suspects, including Jean-Pierre Kwitonda, who was returned to Rwanda in December 2010 after a gacaca court sentenced him to 19 years in prison, and Augustin Nkundabazungu, who was arrested and deported in August 2010 and handed a life sentence with special provisions by a gacaca court of appeal.

Some countries have extradited suspects to Rwanda despite the lack of treaties. Since the ICTR first transferred a case to Rwanda in 2011, Canada, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, and the United States have extradited suspects. Some extraditions have been based on verdicts by gacaca courts.

In December 2018, Wenceslas Twagirayezu was extradited from Denmark to Rwanda. He is alleged to have participated in a massacre in a church and university in which more than 1,000 people were killed. Rwandan media reported that he appeared before the Kicukiro Primary Court for formal charging and hearing on pretrial detention in January 2019.

Twagirayezu is the second Rwandan extradited from Denmark to Rwanda, after Emmanuel Mbarushimana, who was sentenced to life in prison by the Chamber for International Crimes in Kigali in December 2017 over his role in the genocide. He petitioned the European Court of Human Rights, which upheld the Danish court’s decision to extradite Mbarushimana to stand trial in Rwanda in 2014.

The first genocide suspect extradited by Germany was Jean Twagiramungu, who was deported to Rwanda in August 2017 to face trial. Rwandan authorities also requested the extradition or trial of four other genocide suspects from Germany, while welcoming the prosecution of suspects in Germany.

Canada extradited Léon Mugesera, a former academic and government official accused of using incendiary speech to incite the killings, in January 2012. His trial at the High Court in Kigali began in February 2012, where Mugesera faced several charges, including planning and public incitement to genocide. After a complex trial, he was sentenced to life in prison in April 2016 and his appeal is underway.

In November 2016, Canada extradited Jean-Claude Seyoboka, who stands accused of genocide-related crimes, including rape. Seyoboka is a former member of the armed forces and is on trial in a military tribunal.

After years of appeals, the Netherlands extradited Jean-Baptiste Mugimba and Jean-Claude Iyamuremye in November 2016, and both are on trial in Rwanda. Charles Ndereyehe Ntahontuye, another suspect, was tried in absentia by a gacaca court. In March 2018, the National Commission for the Fight against Genocide in Rwanda asked the Netherlands to arrest and extradite him or to try him, and extradition procedures are ongoing.

On March 10, 2013, Norway extradited Charles Bandora to Rwanda. The Chamber for International Crimes at the High Court in Kigali convicted him of conspiracy, genocide, and murders as crimes against humanity in May 2015 and sentenced him to 30 years in prison. The prosecution argued that Bandora was so influential in his commune that the mayor, soldiers, and police, as well as the Interahamwe, militia attached to the ruling party, obeyed his orders. In November 2018, he appealed his sentence, arguing that the evidence used to establish his responsibility in arranging and chairing a meeting on April 7, 1994 to plan the killing of Tutsis who had taken refuge at the Ruhaha parish, was unfounded.

Another genocide suspect Leopold Munyakazi was deported from the United States to Rwanda on the basis of an international arrest warrant charging him with genocide, conspiracy to commit genocide, and denying the genocide. A lower court in Rwanda convicted him for direct involvement in the genocide and sentenced him to life in prison in 2017. The Chamber for International Crimes overturned the life sentence in July 2018, but upheld a nine-year sentence for genocide denial. Other cases include Jean-Marie Vianney Mudahinyuka and Marie-Claire Mukeshimana, both convicted of genocide crimes in absentia by gacaca courts, and in January and December 2011, respectively, were transferred to Rwanda to serve their sentences.

Although increasing numbers of countries are extraditing genocide suspects to face trial in Rwanda, some refuse to do so.

In December 2015, a United Kingdom district judge, after assessing the trials of previously extradited suspects and the updated legal framework in Rwanda, rejected an extradition request for five Rwandan genocide suspects due to risks they would not get a fair trial in Rwanda. Vincent Brown, also known as Vincent Bajinya; Charles Munyaneza; Emmanuel Nteziryayo; Celestin Ugirashebuja; and Célestin Mutabaruka were held in the UK in 2013 after an extradition request from the Rwandan government.

French courts have also denied multiple extradition requests by Rwandan authorities for varying reasons, including concerns regarding fair trial standards.

Human Rights Watch agrees that when it is possible to guarantee fair trials, it is best to prosecute grave international crimes such as genocide and crimes against humanity where they were committed, close to the victims and the affected population. However, if, as in Rwanda, the justice system lacks full independence and the government can influence the outcome of trials, especially in politically sensitive cases, Human Rights Watch has concerns about the suspects’ ability to secure a fair trial in domestic courts.

Trials Abroad

Over the past 25 years, national authorities in some of the countries where Rwandan genocide suspects are living have investigated their alleged involvement in genocide-related crimes and tried a number of them before these countries’ courts.

Typically, national authorities are only able to investigate a crime if there is a link between their country and the crime. The normal linkage is territorial, meaning that the crime, or a significant element of it, was committed on the territory of the country wishing to exercise jurisdiction (territorial jurisdiction principle). Many countries also prosecute on the basis of the personality, meaning that the suspect is a citizen of that country (active personality principle), or the victim of the crime is a citizen (passive personality principle).

However, some national courts have been granted the jurisdiction to act even without a territorial or personality link. This principle – universal jurisdiction – can normally only be invoked to prosecute a limited number of international crimes, including war crimes, crimes against humanity, torture, genocide, piracy, attacks on UN personnel, and enforced disappearances.

Some countries have created specialized war crimes units within their law enforcement and prosecution services focused on addressing grave international crimes committed abroad, including genocide.

Several countries have tried Rwandan genocide suspects, including Belgium, Canada, Finland, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, and Switzerland. For some, it was the first cases of genocide tried in their domestic courts. Criminal investigations are still ongoing against other Rwandan genocide suspects in several countries including France and Belgium.

In France, where many known genocide suspects fled after the genocide, it was not until February 2014 that the first suspect – Pascal Simbikangwa, a former intelligence chief under the Habyarimana government – was tried. This was the first case brought to trial by the newly created war crimes unit. It was a significant moment, as France had backed the former government of Rwanda and supported and trained some of the forces that went on to commit genocide. On March 14, 2014, a Paris court found Simbikangwa guilty of genocide and complicity in crimes against humanity and sentenced him to 25 years in prison. His conviction was upheld on appeal in May 2018.

On July 16, 2016, a French court sentenced Octavien Ngenzi and Tito Barahira to life in prison for genocide and crimes against humanity. Their life sentences were upheld on appeal in July 2018. Several other cases are still ongoing in France, but progress has been slow. France has rejected extradition requests for many people who are the subject of Rwandan-issued international arrest warrants.

Sweden convicted three Rwandans naturalized in Sweden of genocide and crimes against international law. The first person to be tried for genocide in Sweden was Stanislas Mbanenande, who was granted Swedish citizenship in 2008. He was convicted and sentenced to life in prison in June 2013. His conviction was upheld on appeal in June 2014.

Sweden tried Sadi Bugingo under universal jurisdiction, convicting him of aiding and abetting genocide and murders in February 2013. The judges unanimously found him guilty for the killing of 2,000 people in three different attacks. He was sentenced to 21 years in prison and the sentence was upheld on appeal in August 2014.

Canada’s first prosecution under new legislation on grave international crimes was also a Rwandan genocide case. Désiré Munyaneza was found guilty of genocide, crimes against humanity, and war crimes and sentenced to life in prison in 2009.

Trials in Belgium, the Netherlands, and Germany on genocide, war crimes, and incitement charges have also led to convictions.