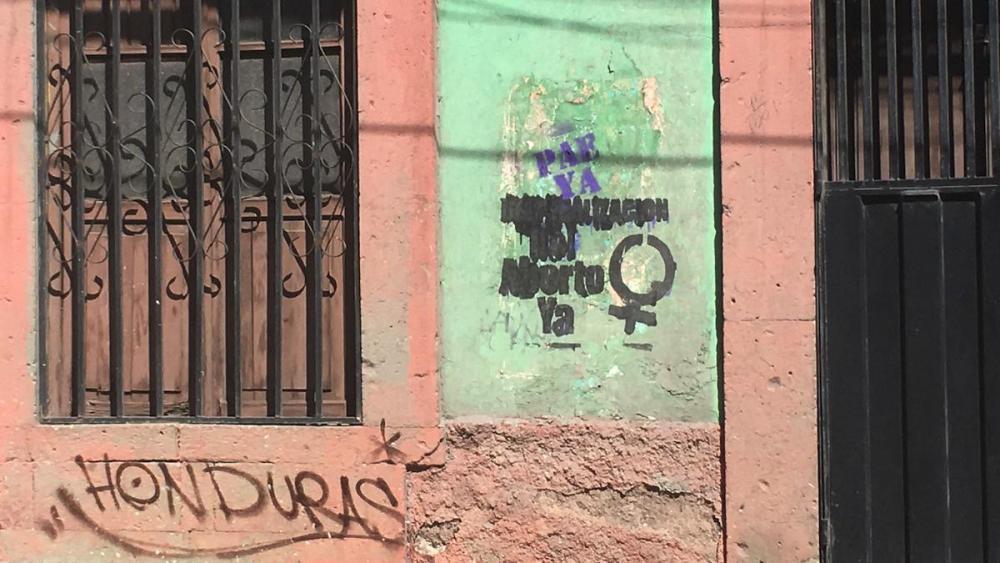

Abortion in all instances, including rape, is illegal in Honduras. Any woman who has an abortion, and anyone found to have helped her, can be charged with a crime and imprisoned.

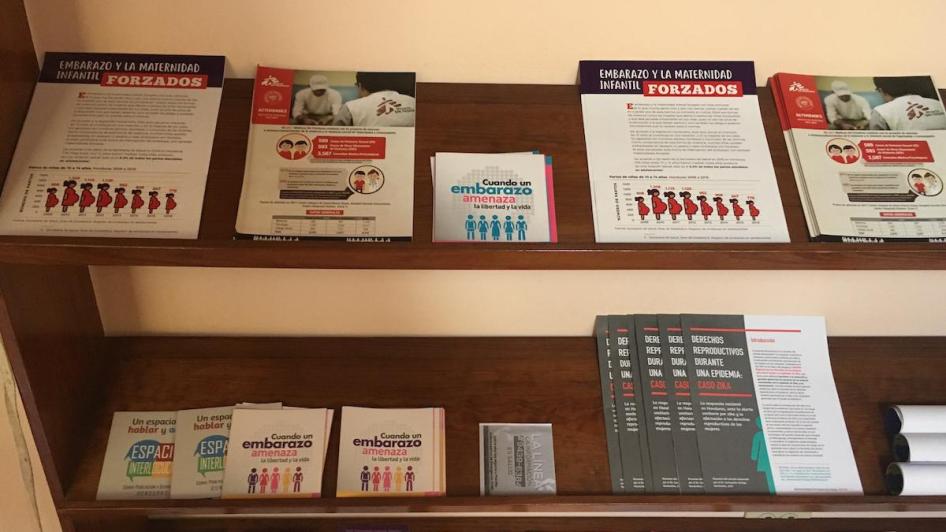

For that reason, La Línea (“The Line”) was a rare resource in Honduras. Mentioned in whispers among friends or seen on flyers passed out at universities or high schools in the capital of Tegucigalpa, La Línea was one of the only places where Honduran women could find accurate information about abortion.

But at the end of August 2018, La Línea’s phone line simply stopped working, leaving many women who needed information and support without anywhere to turn.

The women who ran La Línea were volunteers. They did their work in secret and knew the risks. Abortion is a deeply divisive issue in the country, where both Catholic and evangelical churches support the government’s strict prohibition. Still, after two years of giving desperate women information about abortion – and shortly before the line went down – the staff of La Línea decided they had to reach more women. That August, they tried to place an ad, which included their phone number, in a daily newspaper, La Tribuna. The paper refused to run the ad. Not long after, the organization’s cell phone stopped working and they received an error message saying the network couldn’t be reached.

Fearing for their safety, La Línea’s volunteers needed a plan to reopen the line. If the newspaper had reported the phone number to authorities, bringing the phone to one of the telecom provider’s offices could expose them. But scrapping the SIM card and changing phone numbers would leave the women who knew about La Línea with the wrong number. In January, they decided they had to try to reopen the line. Too many women needed their help. And the women of La Línea had a plan – the first step meant confiding in a friend who worked for the telecom company.

They promised to keep us updated.

***

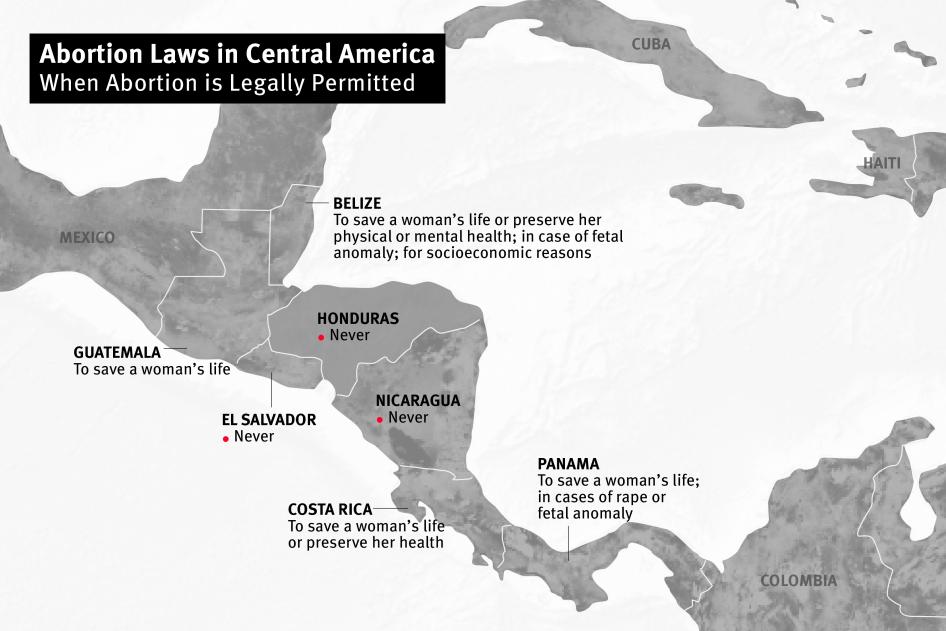

Abortion in Honduras is illegal in all circumstances, including rape and incest, when a pregnant woman’s life is in danger, and when the fetus can’t survive outside the womb. The government also bans emergency contraception, often called the “morning after pill,” which is used to prevent pregnancy after unprotected sex or a contraceptive failure.

Additionally, violent crime is rampant in Honduras, which has one of the world’s highest murder rates. Every 22 hours, a woman is violently killed. Nearly one in four women in Honduras has been physically or sexually abused by a partner, according to a 2011-2012 government survey. At least 40 percent of pregnancies are unplanned or unwanted at the time they occur. Some unintended pregnancies are caused by rape.

Additionally, more than 30,000 adolescents ages 10 to 19 give birth in Honduras each year. While not all these pregnancies are unwanted, girls can have more to lose from an unplanned pregnancy – like missing out on school or being pressured to get married before they’re ready – and can feel the need to take risks to end one. Girls may also have less information about safely ending pregnancies, putting them at risk of complications should they choose to have a clandestine abortion.

Here’s the thing: Research from around the world has shown that when abortion is banned, women don’t have fewer abortions – they just have riskier ones. This endangers their health and even their lives, if the methods are unsafe or if complications are not treated quickly. Women in Honduras end pregnancies “with a lot of fear, a lot of misinformation,” an advocate told us.

United Nations experts agree that refusing women and girls access to abortion threatens their human rights and sometimes can even amount to torture, such as in cases of rape when women are forced to carry an unwanted pregnancy.

No one knows exactly how many women and girls have clandestine abortions in Honduras, but one Honduran nongovernmental organization (NGO) estimated somewhere between 50,000 and 80,000 abortions occur each year. Local experts are unsure of how many people have been imprisoned for either having or providing illegal abortions, but stories of women arrested for suspected abortions make headlines each year. No one has been convicted under the abortion articles of the criminal code in the last three years, according to data provided to Human Rights Watch by the Honduran Attorney General’s office, but seven people were accused of having or providing abortions, and two were detained.

Lorena – Facing Jail

Lorena* (all names followed by* are pseudonyms to protect identity), 22, may soon go to prison after having a miscarriage because doctors accused her of trying to have an abortion.

It started two years ago, when her mother took her to the hospital because she was suffering intense abdominal pains. She had been rubbing her belly, trying to relieve the spasms.

At the hospital, the doctors discovered she was having a miscarriage. She was shocked; she had no idea she was pregnant. She had been spotting, but her period was often irregular. She wasn’t showing other signs of pregnancy, even though she was told she was in her second trimester. Lorena’s life was in danger. The doctors operated and barely managed to save her uterus.

But the doctors also called the police. They saw marks on her belly and assumed she had tried to end the pregnancy.

“They thought I’d hit myself with something to try to hurt myself. I told them it was because I was rubbing my belly.”

But the doctors didn’t believe her.

The minute she was released from the hospital, police handcuffed her and took her to jail. She was detained for two days, and then put under pretrial supervision. Her family is poor and live in a rural village outside Tegucigalpa. Every Friday, she has to travel two hours from her home to the capital, sign a form at the court, and travel two hours back again. Many times, she can’t afford bus fare, and her mother or neighbors pay her way.

This has gone on for two years. If she stops signing the form, authorities could detain her until her trial.

When Lorena met her new court-appointed lawyer this January, the lawyer recommended she plead guilty. That way she would only serve two to three years in prison, as opposed to the four to six years if found guilty, the lawyer said.

The lawyer also told Lorena that her court hearing, which would decide her fate, would take place in roughly a week.

When Lorena speaks of her experiences, you can sense her folding in on herself with fear, seeming smaller and younger than she is. We met her a handful of days after she spoke with her new lawyer, but before the scheduled court hearing. When we asked what she thought of her lawyer’s advice, she looked down and gently shook her head no.

Lorena’s case was horrifying. The only “evidence” doctors had for reporting her to the police was the marks on her belly. Yet Lorena could still go to prison.

A few days later, Lorena’s hearing was postponed. Then it was postponed again. As of May, she was still taking a bus weekly to sign her name, awaiting her court date.

Regina Fonseca - Supporting Women’s Choice

Lorena is just one victim of Honduras’s harsh abortion law. Regina Fonseca, founder and advocacy coordinator of the group Centro de Derechos de Mujeres (Center for Women’s Rights, CDM), knows no shortage of heartbreaking stories. Fonseca told us about one indigenous woman who was raped by two men, apparently as an attack against her father, a cacique, or indigenous leader, whose land they wanted. Unable to get an abortion, the woman gave birth to the child. Her husband left her, and she felt she had no choice but to leave her community out of shame. Her rapists were convicted but spent only three months in jail. Violence against women is rarely punished as it should be in Honduras.

A second woman was denied an abortion and forced to continue a pregnancy against her wishes after doctors told her the fetus had anencephaly, a fatal brain disorder. The baby died hours after she gave birth. “It was weeks of living torture for her and her husband,” Fonseca said.

Fonseca founded CDM nearly 30 years ago. Today, their offices are sun-filled and painted a salmon color, the radio behind the front desk playing upbeat 80s pop. It’s a welcoming space. Fonseca herself vibrates with energy, fueled by a never-empty cup of coffee.

“From the very beginning, we wanted to change the criminal code,” Fonseca said. CDM was founded to work for women’s rights, empower women, and advocate for political change. One of the organization’s biggest victories was helping push through new legislation to protect survivors of domestic violence in 1997.

They see access to abortion as essential to the rights of Honduran women. In 2017, more than 8,600 women were hospitalized for complications from abortion or miscarriage in Honduras, according to data from the health secretary. Women seeking medical attention for miscarriage and abortion often have the same symptoms, like bleeding and pain. And in countries where abortion is illegal, women experiencing complications from abortion often feel forced to claim their symptoms result from miscarriage. The health secretary reported that only one of the 23 maternal deaths in Honduras in 2017 was caused by abortion, but the number may well be higher. Research shows that in countries where abortion is criminalized, deaths from unsafe abortion are more likely to be misattributed to other causes because patients don’t report what happened and doctors can’t always know. Globally, at least 8 percent of maternal deaths are caused by unsafe abortion.

“Women suffer alone in silence,” Fonseca said. And while clandestine abortion has become safer because of medical advances and some access to medication to induce abortion, these pills are not widely available. They are also expensive. Women told us they paid anywhere from 1,500 (US$61) to 7,000 ($285) lempiras – a large sum for people living in one of the poorest countries in Latin America where nearly one-third of the population lives on less than US$3.20 per day.

Doctors – Caught in the Middle

As an obstetrician-gynecologist in a public hospital, Silvia* estimates five to 10 women arrive each day seeking emergency treatment for complications, such as infections or heavy bleeding, from a miscarriage or an abortion. She’s treated women who had unsafe abortions. She chooses never to tell the authorities despite the fact that the law treats abortion as a crime.

She spoke with us in a white-tiled room with a door you can’t see through. She told us how, years ago, she treated a patient who tried to end a pregnancy by inserting a metal stick in her vagina. As more women have been able to obtain abortion pills and avoid such dangerous methods, the number of women and girls she’s treated for unsafe abortions has dropped over the last decade. But even with the pills, things can go wrong.

“If abortion were legal, there would be fewer complications,” she said.

Silvia believes that by not reporting women who come to her hospital after an abortion, she could put her job at risk. But she believes women have good reasons for the decisions they make. “There’s a story behind an abortion. It could be a rape. It could be that you’re pregnant and you’re afraid that you can’t care for a child because of the economic situation in this country.”

The trickiest cases involve women who come to the hospital with a pregnancy that endangers their lives, for example, if they have preeclampsia. “You have to end the pregnancy to save the patient,” she said. But it’s illegal to do so. Yet if a patient dies, the doctor will be investigated.

Still, in these instances, she said she “always acts in favor of the patient.”

The law forces doctors to make difficult choices – choices many feel are unethical. For example, when a fetus isn’t viable, or able to survive outside the womb, legally doctors can’t intervene to end the pregnancy – even if the woman is suffering and has asked for this help. Some doctors’ decisions effectively force women to continue such a pregnancy and give birth, only to have the baby die shortly thereafter.

Doctors have a duty to act in the best interest of their patients, and this law undermines their ability to fulfil that duty. “You can’t judge someone in the moment you are treating them,” she said. “If you judge, you’re losing what it means to be a doctor.”

The Plight of Rape Victims

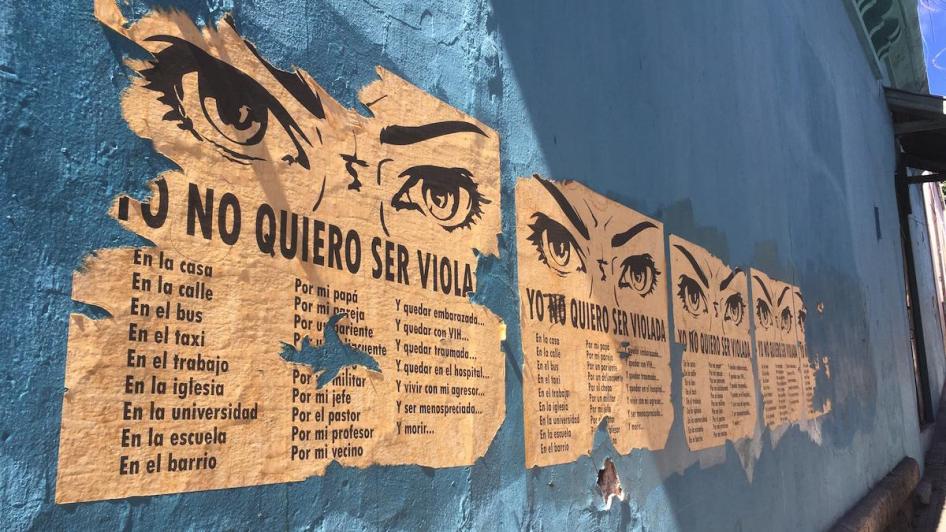

The prohibition on abortion and emergency contraception puts rape victims in an especially precarious position.

Cristina Alvarado is a social worker and part of the national coordination team at Visitación Padilla, a women’s rights organization that helps female victims of violence, including rape. Alvarado has met girls who were 16, 15, or even 12 years old who became pregnant as a result of incest or rape, and were forced to continue their pregnancy.

In 2017, 820 girls ages 10 to 14 gave birth in Honduras, according to data from the health secretary. As 14 is the age of sexual consent, under the law, many of these girls became pregnant from rape.

When women or girls are raped, many want to bury their memories of the traumatic event. This is impossible if the government is forcing them to bear their rapists’ child. “To have to continue with an unwanted pregnancy that resulted from abuse, it’s almost torture,” Alvarado said.

In cases of sexual violence, “the first 72 hours are critical,” said Dr. Rafael Contreras O., a medical doctor from Colombia who has worked with Médicos Sin Fronteras (MSF) in Honduras since September 2017. During this period, doctors can give rape victims medication to try to prevent HIV and pregnancy.

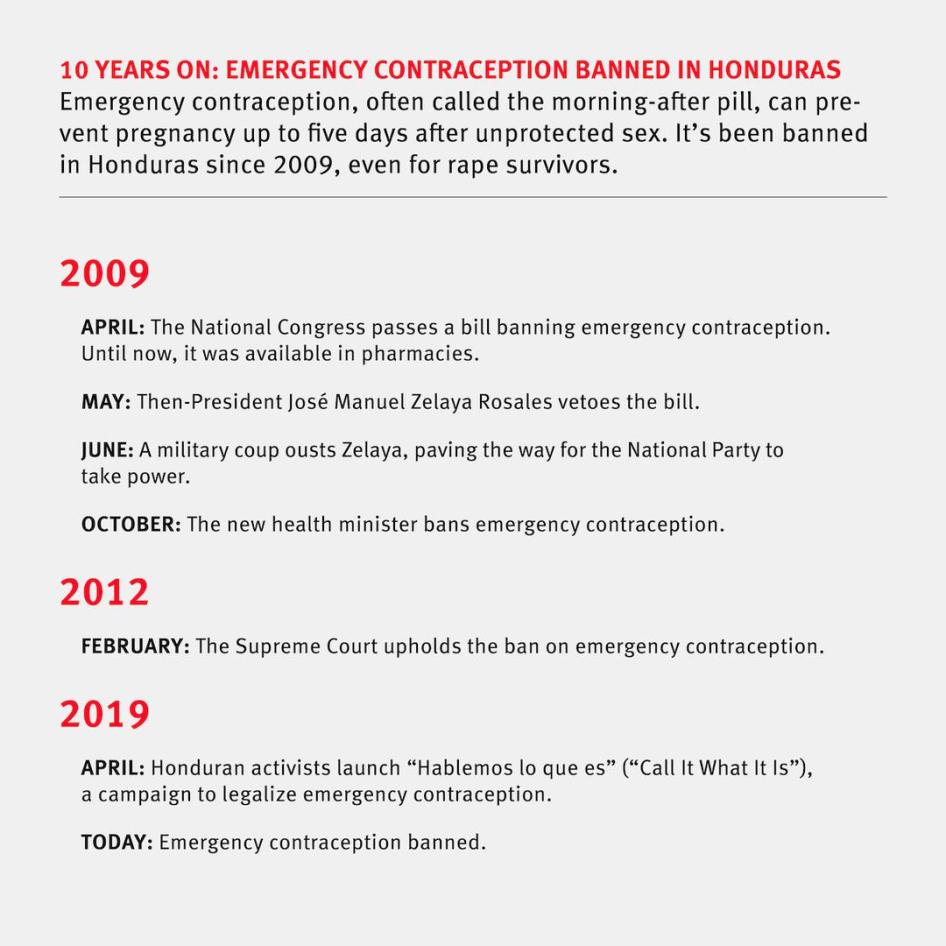

Emergency contraception can prevent pregnancy up to five days after unprotected sex. But it’s illegal in Honduras.

This means rape victims who come to MSF wanting to prevent a pregnancy can’t get the help they need. Instead, providers offer an outdated and less effective method to prevent pregnancy that works only about half the time.

When asked what MSF could do to help women who become pregnant from rape and don’t want the pregnancy, Dr. Contreras shook his head: “Here? Not much, no,” aside from offering psychological support.

Emergency contraception was outlawed in Honduras in 2009. A few months after a military coup ousted then-President José Manuel Zelaya Rosales, the new de facto health minister issued a regulation banning emergency contraception. Honduras’ Supreme Court upheld this move in 2012.

Emergency contraception can still be bought illegally in some pharmacies, but the price is high and quality uncertain.

In April, activists launched a campaign to legalize it. MSF has also advocated for emergency contraception to be made legal again in Honduras, Contreras said. But even though it’s not an abortive and cannot end or harm a pregnancy, some groups intent on restricting reproductive rights spread misinformation, calling it the “emergency abortion pill,” he said.

Contreras said this too drives women underground. Ultimately, he said, “women who want an abortion will get one.” As long as abortion is illegal, this can mean an unsafe abortion that leads to bleeding, uterine perforation, and even death.

Verónica* – A Family Saga

“My eldest daughter is a product of rape, and it still hurts,” she said.

Verónica, the mother of two adult daughters, sat ramrod straight as she tells her story. Determined and serious, she broke down and cried at times as she revisits the painful memories.

She was 21 years old when her boyfriend said he wanted to take her on a trip. She was from the country, a small town, and it sounded like fun. He took her to the middle of nowhere and stopped the car. “He said, ‘If you don’t have sex with me, I’ll leave you here.’”

She didn’t know what else to do, so she had sex with him and became pregnant. She was five or six months along before she realized she was pregnant. She was studying at the time and had to leave school. “Everyone in the neighborhood pointed at me.”

She gave birth to her first daughter. Later, she married and had a second daughter. She has never been able to love them equally. “My family always says, ‘Why don’t you love your eldest?’ But I cannot compare the two loves,” she said. This lack of affection affects the whole family; not surprisingly, the sisters also don’t get along.

Her younger daughter was a university student when she became pregnant. “I was remembering everything that happened to me when my daughter got pregnant.”

Verónica told her that if she did not want the baby, there was a way out. Her daughter didn’t want to become a mother so Verónica got the pills, knowing that at any moment she could go to jail for it.

Verónica gave her daughter the pills. The process triggered by the pills can be very painful, and Verónica’s daughter was in so much pain, the only part of her body she could move was her eyes. Her mom held her hand. At times, Verónica wanted to take her to the doctor, but her daughter said no, fearing they could go to prison. So they stayed.

Two months after the abortion, she finally took her daughter to a doctor to make sure she was all right. The doctor said, “This girl was pregnant.” Verónica and her daughter denied any knowledge of a pregnancy.

“I’m a single mom, and I don’t want my daughter to be a single mom,” she said, her voice steely. “I did it, and I don’t regret it.”

Abortion Behind Closed Doors

Women dealing with an unwanted pregnancy in Honduras are forced to contemplate life-altering choices: If I have a child, I’d have to drop out of school and my life dreams would be shattered. Or, I already have three children, and I just can’t handle any more. Or, I don’t have enough money. Additionally, any form of contraception, no matter how carefully used, can fail. A condom breaks, a birth control pill is missed or ineffective due to illness.

The women we interviewed who had obtained an illegal abortion often described how disastrous the effect would have been on their life had they been forced to continue the pregnancy.

Maria* learned that she was pregnant shortly after leaving a violent partner who had hit her on the head and thrown her in front of moving vehicles. She didn’t have a job or a home and already had three children. She couldn’t afford another child, so she scraped together 7,000 lempiras (US$285) for the pills. She went to her sister’s home and took them; her brother and sister watched over her. The pain was so intense she lay awake all night, feverish, her sister making her cinnamon tea, her brother holding her hand.

She was afraid to go to the hospital, sure she’d end up in jail. A few years earlier, a friend had gone to the hospital after a clandestine abortion and doctors threatened to report her to the police. “I felt between a rock and a hard place, not knowing what to do,” she said.

After much begging by her siblings, she finally agreed to go to the hospital. “They were afraid I would die,” she said. Her sister lives in a poor area on the outskirts of Tegucigalpa, and the cab ride took an hour and a half. Her pain intensified. At the hospital, her doctor treated her kindly. Her uterus was coming out, he said, but he could reinsert it. But the pills hadn’t worked. She was still pregnant. “You’re in worse shape than your baby,” he teased her.

Now, she’s a mother of four children.

Andrea*, a college student, learned she was pregnant after taking a home pregnancy test in the stall of a university bathroom. “I was so afraid. I didn’t have any money to take care of a baby—I’d have to drop out of school,” she said.

Her partner gave her 3,500 lempiras (US$143) to go to a “seedy” underground pharmacy to buy the needed pills. She was alone in her apartment when she took them, and while she experienced a fever and started vomiting from the pain, there was only a little bleeding. She knew an incomplete abortion could lead to an infection and even death. “I got really scared.”

A free ultrasound at the hospital the next day told her she was still pregnant, so three days later, she tried the pills again. This time, the pain tore through her and she bled for hours. But again, it seemed incomplete. A second ultrasound showed the fetus was not viable, but tissue that could cause an infection remained in her uterus.

Horrifyingly for Andrea, the doctor who examined her said she could see Andrea had tried to induce an abortion. Andrea’s mind raced. She worried the doctor would report her. She was terrified, “thinking how many years of jail I could face.” How would she tell her devoutly religious parents that she went to jail for trying to have an abortion?

The doctor was not kind. She gave Andrea a local anesthesia before the procedure to remove the tissue. But the anesthesia didn’t work. She could hear the sound of them scraping her uterine wall – the fiercest pain she’d ever experienced, she said, wiping a tear from her eye. “I think it was on purpose. Like ‘I won’t report her, but she will remember how this hurt.’”

She lay awake that night in terror expecting the police to come for her at any moment. They didn’t. After living through this, she said, “I became a feminist.”

The Role of the Church

It’s impossible to understand how abortion is viewed in Honduras without considering the outsized role religion plays. Conservative Christian churches, both Catholic and evangelical Protestant, are extremely influential and the vast majority of Hondurans belong to one or the other. A massive Catholic basilica, completed in 2005 and painted in striking shades of gray, can be seen from most of Tegucigalpa. In the mountains overlooking the capital, people visit a statue of Christ that surveys the whole city.

While the top leadership of both these churches remain implacably opposed to abortion, not all church leaders feel the same way.

Iglesia Cristiana Ágape, a small evangelical Protestant church north of Tegucigalpa, is awash with natural light. A cross, made of orange and gold glass and bright with sunlight, is embedded in the wall behind the pulpit.

The church has a policy on emergency contraception and believes it should be legal and available to women. While the church has no official position on abortion, one of its pastors, David Del Cid, has spoken out publicly for the legalization of abortion in cases of rape or incest, when the women’s life is in danger, or if the fetus won’t survive – referred to as the “three circumstances” (tres causales). He also advocates for other causes, like defending the rights of indigenous groups and lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people.

It’s no surprise that this is the church that Ana Ruth Garcia, known as Pastora Ana Ruth, chooses to attend.

Garcia has a wide smile and a bold personality that fills a room. She is known among the feminist community for forming a group of religious women, called Ecuménicas por el Derecho a Decidir (Ecumenical Leaders for the Right to Decide, Las Ecuménicas), who support access to abortion and other women’s rights issues. As a pastor, she had visited impoverished women in prison who had been accused of having abortions. The injustice of the women’s plight inspired her to become an activist, including within the church.

She began speaking publicly in favor of ending the abortion ban in 2016, when Las Ecuménicas joined Somos Muchas, a coalition of some two dozen organizations and independent activists trying to change the penal code.

She faced an immediate backlash. People accused her group of not being Christian and said they were following the orders of “crazy feminists,” she said. A cardinal in Tegucigalpa slammed Las Ecuménicas in a Catholic website article, falsely claiming the group was funded by US-based “abortionists.” When she and other women demonstrated in front of the congressional building calling for legal access to abortion, counter protesters threw stones, bottles, knives, and sticks at them.

Despite the organizations’ efforts, only 7 congress people voted to lift the ban, though the National Congress has 128 members. The criminal code’s abortion language remained unchanged.

Because of the threats, Garcia began keeping a low profile and stopped speaking publicly about abortion.

But the threats continued. Garcia told Human Rights Watch that on the night of January 4, 2018, she and her husband went to bed early, and she put her cell phone on silent. But when she woke up in the middle of the night, she saw a string of WhatsApp messages, the last one from an old friend saying, “Where are you, Ana Ruth, where are you?”

The friend had gotten a tip that Garcia and her family could be in danger.

“You need to get out of your house immediately,” her friend said over WhatsApp. Terrified, she grabbed her purse and fled with her husband in their pajamas to their car. Her son was away visiting extended family. They spent the night at a friend’s house. Not long after, Garcia said, her neighbors told her the military police had come by. They went into hiding for a month. The tip from her friend was never confirmed, but the fear of that night haunts her.

“It was the worst nightmare of my life,” she said, her hands braced against her chest. “It still affects me.”

She now lives in a new house, in a new neighborhood. She changed her phone number, her son changed schools. Her office has security cameras. Her son can’t have friends over or tell anyone his address. She still receives threats. One of the latest was a Facebook comment saying she was like Jezebel, the reviled Biblical queen who was killed, carved into pieces, and then eaten by wild dogs as punishment for her sins. Garcia is anxious. When she walks alone, she looks around anxiously in all directions for pursuers.

The Way Forward

Abortion is not a priority for politicians in Honduras right now.

Scherly Arriaga, a second-term Congresswoman from the progressive LIBRE party, was one of the seven congressional representatives who voted to lift the abortion ban. But believing there’s little hope of legalizing abortion – at least for now – she is instead focusing on other ways to shore up women’s rights.

This includes a plan for mandatory comprehensive sexuality education in schools. Once that is set up, she believes, they can work towards legalizing emergency contraception, and from there, allowing abortions in at least the three circumstances.

Last year, she presented an initiative to get better sexuality education into schools, but it was never brought for a vote. She plans on starting again this year and hopes to get the bill onto the floor of Congress for a vote.

“It’s really hard,” she said. “We’re fighting against all the beliefs people have, the stigmas and myths that haven’t been broken down yet.”

“If a woman doesn’t feel ready to be a mother, she shouldn’t have to be. Woman should be able to choose.” She pauses and puts a hand on her belly. “I’m pregnant now and happy to be. It’s my choice.”

The Line is Open

In March, La Línea, the information line for abortion, re-opened. Throughout the winter, the women tried various ways to get the line working again. All had failed. On impulse, they simply tried buying a new phone, keeping the same number.

It worked. “I was very nervous at the first call,” one of the founders said, feeling she was out of practice. “But at the same time, excited to be helping another woman who is obviously seeking answers.”

They quickly spread the word of their return and now receive more calls than ever from women and girls, begging for information about safe abortions, asking about contraception, or in need of the morning after pill.

They hope that the revival of La Línea will mean fewer women resort to dangerous methods to end an unwanted pregnancy. “I want to make sure that women don’t go through that,” one of La Línea’s founders said. “I want to show them that abortion can be safe.”