Why is this bad for workers?

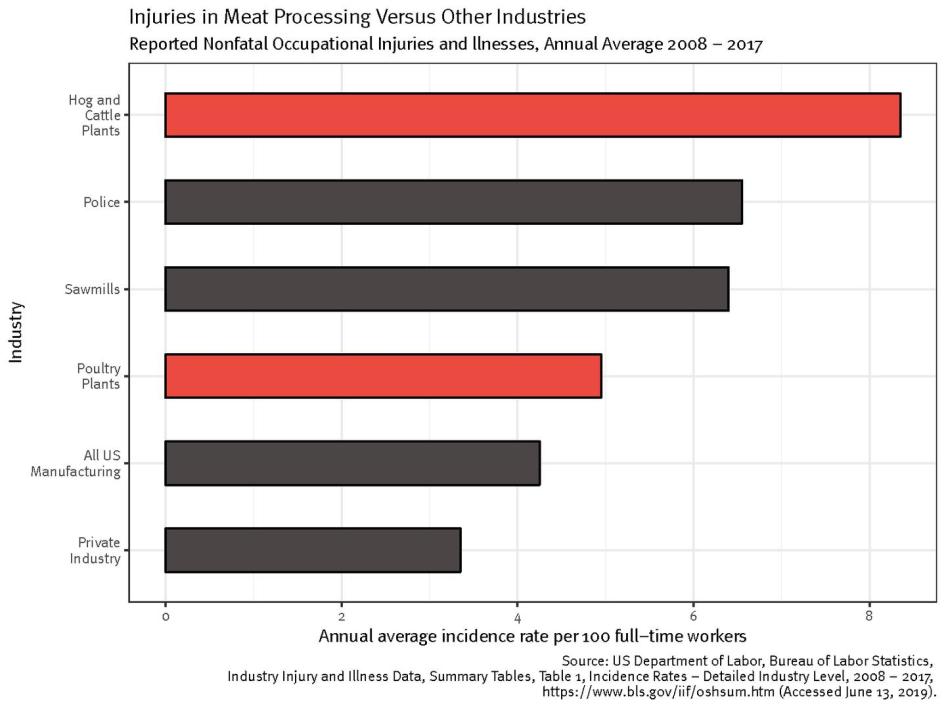

The faster you have to do your job the more likely you are to get hurt – to cut yourself by accident, or get caught in machinery, or develop a musculoskeletal disorder.

Almost every worker I interviewed spoke about dealing with chronic pain. A number of older workers had limited ability to use their hands after years on the line. I spoke with a mother and her son who worked at a Nebraska cattle plant, and watched as the son grabbed a bottle of water and opened it, giving it to his mom. It’s a force of habit, he said, because his mom can’t do it anymore. That resonated with what a lot of workers – regardless of age – told me. When they come home from their shift, some can’t open jars, some can’t use a comb for their hair. Some workers wake up at night because of the nerve pain.

What else will increased line speeds lead to?

Companies, particularly poultry producers, rely on chemicals to make sure that their meat is safe to eat. Some workers’ health and safety advocates argue that, with increased line speeds and fewer food safety inspectors on the line, companies will end up relying on chemicals even more.

The use of chemicals is already a problem for workers. Throughout the meatpacking process, companies – particularly poultry companies – spray water laced with a highly irritating chemical called peracetic acid. It’s a chemical approved by the government for use in plants, but there are no rules when it comes to how much workers can be exposed to. Companies spray it on the meat or dip the meat into the mixture – and as a result a lot of workers are essentially fumigated while they work. This chemical is abrasive to workers’ eyes, nose, and throat. Their eyes tear up and cry. Many cough.

Almost all the poultry workers talked about constantly having sinus issues because of their exposure. Some workers told me they are terrified to blow their noses because of the blood. They believe it’s caused by the chemicals. When some of the people I spoke with complained to supervisors or plant officials about how strong the chemicals are, their companies didn’t do anything about it.

Who are these workers?

The federal demographic data about the industry doesn’t give an accurate picture of who workers slaughtering and processing meat are because it factors in all employees, like truck drivers and office staff. Based on what we know, most of these workers on the line are people of color. Probably about one-third are immigrants, and one study estimates that as many as a quarter of the workforce are undocumented. About two-thirds of the workers I spoke with were Latino and one-fifth were Black. The gender breakdown is fairly even but can vary a lot by plant and position.

Are they unionized?

It depends. I spoke with workers from 12 meatpacking companies. About half the plants featured in our report were unionized, but that’s not representative. Unions are less common among the smaller producers.

Under President Reagan, the industry largely busted the US meatpacking unions, and you can see the effect on workers’ wages. Before 1983, wages for workers in animal slaughtering and processing were generally on par with manufacturing workers’ salaries. By 2002, meatpacking wages were 24 percent lower than the average for a US manufacturing job. This year, it’s 44 percent lower.

Last month, US immigration authorities staged the country’s biggest raid in a decade on a series of Mississippi meatpacking plants, arresting hundreds. Does this affect worker safety?

One of the biggest issues for worker safety is worker voice. Their ability to have a say, to stop abusive conditions. Immigration status has an effect on this. Immigrant workers may be afraid that if they speak up, they could be fired. For undocumented workers, the fear is that they’ll be deported in retaliation for speaking out.

Big, high-profile raids like that in Mississippi amplify fears among workers. One of the plants that was raided had recently settled a class action employment discrimination lawsuit for $3.75 million. There is no indication the raid was retaliatory, but regardless of what triggered the raid, in the minds of workers, it may cause them to fear that speaking up has consequences. Some of those workers arrested in the raid may have been part of a class that fought their employer and won, but they’re the ones who are going to pay.

What did workers tell you about the production pace?

Nearly all the workers I spoke with told me they are pushed to do more and more, faster and faster. It’s stressful work. Some workers cried while speaking with me. Some said their supervisors screamed and humiliated them to keep up production speed. Some told us that supervisors don’t even let workers use the bathroom outside of scheduled breaks.

Did you interview anyone who stood out to you?

One woman in Nebraska, who had most of the flesh seared away from her fingers on one hand after a machine that seals bags of pork chops clamped down on it. She was sobbing when telling me her story, sharing how she stood there for 10 to 15 minutes with her hand in the machine before they could get it out. She still couldn’t use her hand about four months later. She said the day of her accident, the line was moving really fast.

Her story suggests how the mad rush to get product out can lead to terrible injuries. Her injury happened on a Friday and she was told to be back at the plant at 6:30 Monday morning. The company also told her the only way she’d receive workers compensation [money paid to people injured on the job] was if she came in and worked. Since then, she’s been folding gloves with her non-bandaged hand.

Another woman I spoke with stood out to me for the opposite reason. She is 73 years old, has worked in a chicken processing plant in Alabama for decades, and is one of only two workers I spoke with who didn’t experience any pain. When I asked her how she stayed healthy, she said, “hands don’t work as fast as the machine.” She said she can’t work as fast as they want her to, so she works at her own pace.

For me, that highlighted how dangerous the increases in slaughter line speeds could be for workers at slaughter plants who don’t have the ability to regulate how quickly they work – which is what the vast majority of workers we spoke with told us.

What surprised you the most in your research?

How much hasn’t changed for workers in terms of health and safety issues. Human Rights Watch issued a report on this industry in 2005, and we’re still seeing many of the same problems.

The other thing is the lack of federal oversight. The US Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) doesn’t have any standards regulating work speed or chemical exposure in the industry. It’s also seriously understaffed and underfunded. The only agency that regulates line speeds is the USDA’s Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS). But they see the effects of line speeds on workers as being outside their jurisdiction. They don’t see themselves as responsible. And now they’re allowing more chicken processing plants to increase their slaughter line speeds and want to totally end speed limits for pork plants that opt-in to this system. Most advocates think cattle plants will be next. It’s shocking that the government is considering steps that could actually make things worse for workers, when it should be doing what it can to improve conditions.

How can consumers help?

You can sign our petition calling on the Food Safety and Inspection Service to stop lifting line speed limits, which puts workers at risk of serious injury.

Consumers can also do more to demand supply chain transparency from grocery stores, restaurants, and fast food chains. These buyers have more information than consumers about where the meat they eat is coming from. As we’ve seen in industries like cacao and coffee, increasing transparency can be a major step in helping workers’ conditions, and it allows consumers to support businesses that treat their employees fairly.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity