What is different about this moment in Iraq?

In October 2019, a massive protest movement hit the country, with millions of people in the streets. Young people in the center and south of the country came together through a non-sectarian lens to call for basic human rights for all Iraqis, regardless of ethnicity, language, or belief. Their demands and the wave of protests they sparked forced Prime Minister Adel Abdul Mahdi to resign in November, marking the first time popular protests in Iraq led to a change in power.

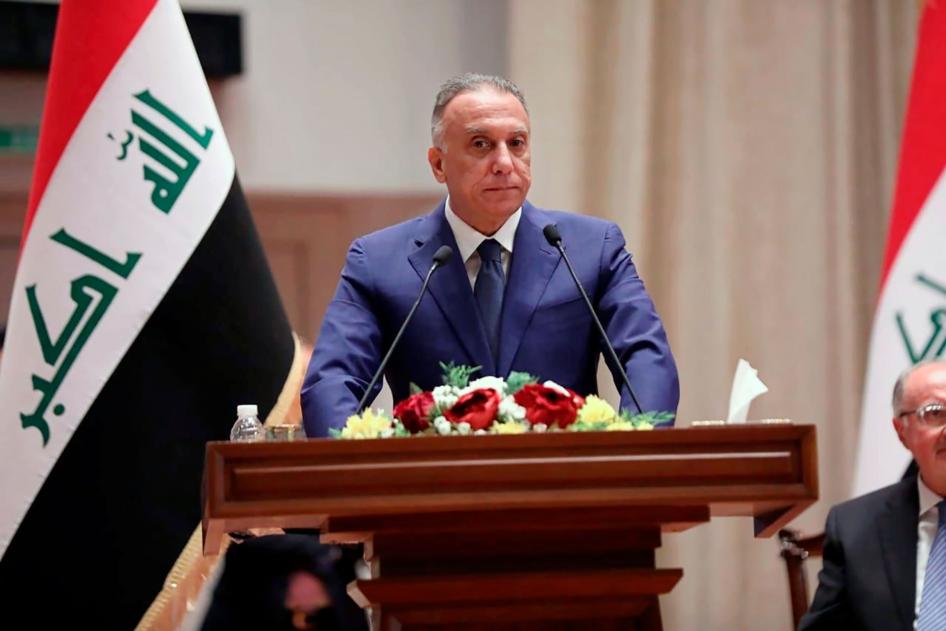

In May, a new prime minister, Mustafa al-Kadhimi, took over. Al-Kadhimi is a former journalist and went into exile under Saddam Hussein. When he came back to Iraq, he became the head of the Iraqi National Intelligence Service. Since becoming prime minister, he has been vocal about tackling some of the most difficult and sensitive human rights issues in Iraq, which is quite incredible. So with this new leadership, there is an opportunity to realize one of the loudest demands of protesters: that authorities reengage with the public.

This is also one of the first times since 2003 where the violence in the country has diminished to the point that Iraqis can start talking about things not related to war. The country has endured years of conflict, through the United States-led invasion and occupation, a civil war, and the Islamic State (also known as ISIS). Now Iraqis can finally demand politicians engage in issues affecting their human rights not through the lens of national security.

But there is another story taking place alongside this. What does your report describe?

Since the fall of Saddam Hussein in 2003, those he oppressed have been interested in opening the country in terms of elections and free speech. But things took a turn in the opposite direction over the last decade. Authorities have dealt with critics not only through violence, which we have seen when protesters were beaten and killed, but also through campaigns using laws to prosecute speech they don’t like, intimidating people into silence.

Who is being targeted in this campaign? Why?

In the autonomous Kurdistan Region in the north, like in Baghdad-controlled areas, there is almost no money for independent media, so most of the outlets are funded by one of the two main Kurdish political parties, or smaller groups. Journalists working for the outlet of one party are often sent to cover protests instigated by that party in territory controlled by another and are sometimes arrested or beaten by Kurdish security forces, or even killed. And prosecutions against journalists are also happening in Kurdistan along political lines.

But this is happening across the country, also in Baghdad and the south. Authorities are using vague legal provisions to target journalists, activists, and frankly, anyone posting criticism on social media, including people writing on their own Facebook pages. This should not be illegal.

In Baghdad, the penal code has provisions that broadly deal with defamation. You could be prosecuted if you say anything that “insults” an Arab country or someone in power, for example. But there is no definition of what constitutes an insult, so these provisions are extremely opaque. Another set of provisions deals with incitement, and authorities use these against people they claim posted something online that could either incite someone to carry out a criminal act or threaten national security. But there is no standard for what this means in practice.

And in addition to being arrested, a lot of these people are getting threatening messages on their phones saying, “You’re next. We’ll kill you if you keep writing about this [topic].” And there is a systemic problem in Iraq where if those receiving threats go to the police, the police do nothing to protect them.

What penalties do people face if found guilty of these vague charges?

Depending on the provision someone is charged under, they could face up to 10 years in prison, a fine of up to about US$800, or both. And some say security forces beat them while interrogating them. But what is interesting is that we documented very few cases where someone is forced to serve an actual prison sentence. Authorities are clearly not interested in filling prisons with these people. I suspect that the point of these prosecutions is to intimidate people so much that the next time they want to post something critical of the government on Facebook, they don’t. It’s about harassment and silencing.

In the course of your research, were there any cases that particularly stood out to you?

One man, Haitham Sulaiman, is a 48-year-old protest organizer based near Baghdad, who got involved taking on corruption in Iraq. In early April, after hearing that the local health department might be making exorbitant profits off the cost of paper masks amid the Covid-19 pandemic, he posted the allegation on Facebook and called on authorities to investigate. The next day, intelligence officers from the Ministry of the Interior came to his house and left a warning that he had to stop writing about corruption. A few days later, four men in plain clothes arrested him and took him to the intelligence office, where they beat him and forced him to sign a document saying the Iraqi protest movement of 2019 had been bankrolled by the US. They then charged him under the penal code for willfully sharing false or biased information that “endangered public security.”

Another woman, “Amal” (not her real name), has protested corruption in Basra for years, been openly critical of different political parties online, and had posted videos of herself protesting in 2018, at the time of large-scale protests in southern Iraq. Around that time, while at home one night, she saw three masked men open gunfire on her house. She fled the city with her children but came back three weeks later. A few days after returning, an armed man came to her house and threatened that if she didn’t leave with her family, they’d all be killed. She has since fled the country.

What hope does the new government offer to address these issues?

The first thing the government should do is institute legal reforms and amend the penal code and other problematic laws to limit the abusive impact of these vague provisions. Security forces should investigate threats and acts of violence against journalists, activists, and social media critics.

But the prime minister, having seen the power of the country’s protests firsthand, should send the message down through Iraq’s government structure that he will no longer put up with those who abuse their powers to go after people who said something they don’t like, and will punish them. And maybe for the first time in Iraq’s history it’s possible this could happen.