Thank you, Mr. Chairperson.

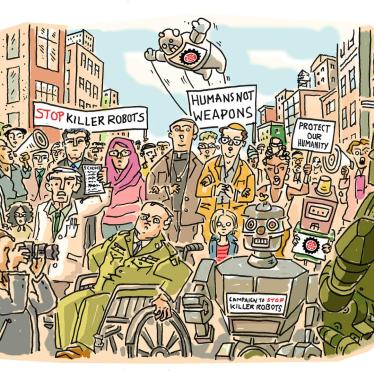

Human Rights Watch, which coordinates the Campaign to Stop Killer Robots, appreciates the presentation by Ambassador Karklins and his efforts to identify commonalities across the national commentaries on the guiding principles. While the guiding principles should not be viewed as an end in themselves, the exercise has led to more substantive discussions at the GGE this week.

Over the past few days, states have presented their commentaries, and other states have added their voices to the debate. In these discussions, we have noted certain emerging commonalities that parallel the key elements of a new legally binding instrument proposed by the Campaign.

First, there is widespread use of the term “human control.” Although some states have used other terms, the vast majority, at least three-quarters, has focused on human control as central to human-machine interaction and essential to compliance with international law and moral standards. “Control” is a stronger and broader term than “judgment” or “intervention.”

Second, states have referred to many of the same components of human control. Human Rights Watch and the Campaign to Stop Killer Robots have distilled those frequently cited components into three categories.

Decision-making components of meaningful human control give humans the information and ability to make decisions about whether the use of force complies with legal rules and ethical principles. The human operator should, in particular, understand the operational environment and how the system functions.

Technological components are embedded features of a weapons system that enhance human control. Examples include reliability and predictability, the ability of the system to relay relevant information to the human operator, and the ability for a human to intervene after the activation of the system.

Operational components limit when and where a weapon system can operate, and what it can target. They encompass, inter alia, temporal and geographic limits on system’s operations.

While none of these components is independently sufficient to amount to meaningful human control, all have the potential to enhance control and they often work in tandem.

A third theme that has emerged this week relates to the structure of a legally binding instrument or “normative and operational framework,” which, as some states have noted, should include a combination of prohibitions and positive obligations.

Most states agree that some form of human control is necessary to comply with international law and moral standards. This principle could be codified into a general obligation to maintain meaningful human control over the use of force.

Several speakers have also referenced prohibitions, and in particular prohibitions on weapons systems that rely on machine learning or target human beings. We believe a new instrument should prohibit weapons systems that autonomously select and engage targets and are inherently morally and legally problematic. Those weapons would include those that lack meaningful human control due to machine learning and those that target humans based on target profiles.

Finally, other speakers have highlighted the need to consider how weapons systems that autonomously select and engage targets are used. Concerns in this area can be addressed through positive obligations that ensure meaningful human control is maintained in the use of such systems.

In conclusion, we encourage states to dig deeper into these frequently cited themes of the debate, and to use them as a basis for negotiating a new legally binding instrument that maintains meaningful human control over the use of force and bans weapons that operate without such control.

Thank you.