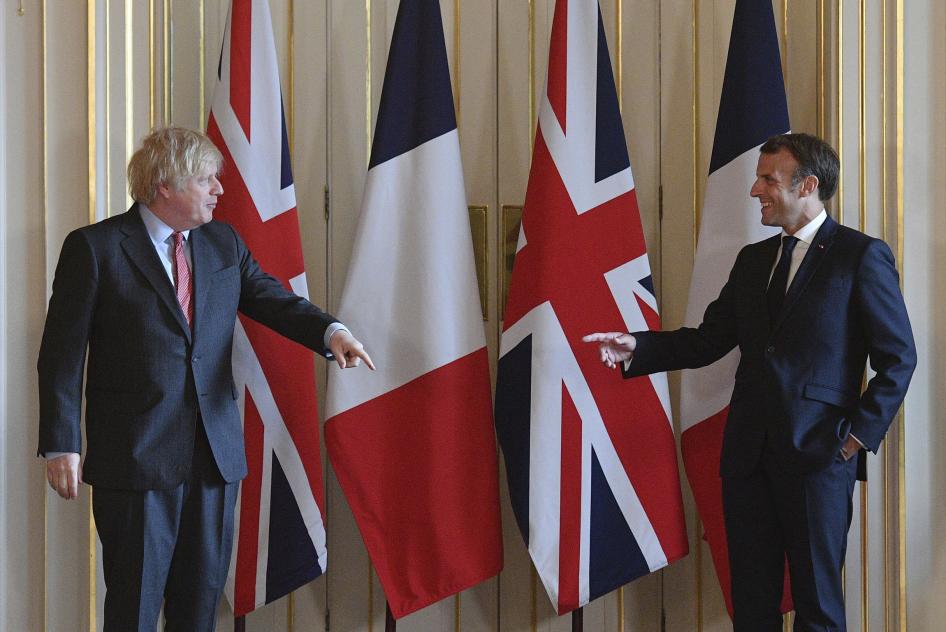

On first sight, President Emmanuel Macron of France might appear to advance a more human rights-friendly foreign policy than Prime Minister Boris Johnson of the United Kingdom, at least judging by the many lofty statements in defense of multilateralism, the rule of law, and human rights that have become Macron’s trademark. Johnson, meanwhile, has openly called for “opt-outs of human rights laws” and caricaturized “lefty human rights lawyers and other do-gooders,” among other troubling statements that are derisive of human rights norms and defenders.

Yet the upcoming membership of both countries to the United Nations Human Rights Council for the 2021-2024 term― both were elected without competition― is likely to confirm a startling reality. To date, at least, acting from the margins of the Council, France is largely missing in action while the United Kingdom, to its credit, has led on some important country-specific situations.

Indeed, over the past year, the United Kingdom played a major role in the negotiations at the Human Rights Council, leading to the establishment of a fact-finding mission on Libya in June, as well as in drafting a joint statement in July that criticized China for the human rights situation in Xinjiang and Hong Kong― building on a previous one in 2019, also led by the United Kingdom. It has also led joint statements on human rights crisis in Cameroon and Chechnya and has been a member of several core groups leading on country-specific situations: Iran, Somalia, South Sudan, Sri Lanka, and Syria. Earlier, while Johnson was foreign minister, the United Kingdom was a major mover within the EU to get the Council to establish a quasi-prosecutorial investigative mechanism into alleged ethnic cleansing of the Rohingya in Myanmar.

Although the United Kingdom has been inconsistent, taking strong positions on concerns in some countries while downplaying the same concerns elsewhere, France has been missing opportunities to be an active player. It has largely refused to lead on country-specific situations, beyond Eritrea and Syria, joining five (Australia, Austria, Belgium, Germany, Netherlands) and nine (Germany, Italy, Jordan, Kuwait, Morocco, Netherlands, Qatar, Turkey, United Kingdom) other members in the respective core groups. Smaller states like Iceland― with far less global influence and bandwidth― initiated scrutiny of the human rights situation in both the Philippines and Saudi Arabia.

But France under Macron has not initiated any country-specific scrutiny by the Council. In fact, it has failed to use its influence and leverage within the EU and beyond to increase support for human rights initiatives led by its own European allies, and at times opposed or belatedly and resignedly joined such initiatives.

The United Kingdom has led inconsistently, and there are both good and bad reasons, including bandwidth limitations and double standards to name two obvious ones. But France has consistently trailed behind. Paris has sought to rationalize its absence and silence by insisting that it does not want to weaken EU unity by joining initiatives that do not enjoy full EU support, yet it does not actively seek to build such support either.

Its “strategy” is also counterproductive as France is effectively handing a veto to the lowest common denominator within the EU, including Hungary and Poland which are facing Article 7 proceedings under the European Union Treaty due to their own violations to the rule of law and human rights.

The latest example of how France and the United Kingdom have differed was the September 15 joint statement on Saudi Arabia delivered by Denmark. While the United Kingdom was among the 29 countries subscribing to the statement when it was delivered, France only did so post facto. Where they both stand shamefully together is with regard to their continuing arms sales to Saudi Arabia despite war crimes by the Saudi- and Emirati-led coalition in Yemen.

In a major foreign policy interview, President Macron recently decried the “relativism […] that is the game of powers that are not comfortable with the United Nations human rights framework. There is very clearly a Chinese game, a Russian game on this matter, which promotes playing down values and principles.”

While he is right, he should also look closer to home and shed the silence that has marked his own “relativism” with serious rights abusers such as China, Egypt, Russia, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, to name the most obvious. His use of euphemisms regarding the dire human rights situation in Egypt during the recent state visit by President Abdel Fattah Al-Sisi is a tell-tale example of the very “relativism” he decries elsewhere.

While stating that “a dynamic, active, and inclusive civil society remains the best barrier against extremism,” Macron refused to call Sisi to account, though he has presided over the worst repression of civil society in Egypt in decades. If there is one actor in Egypt who has persistently and brutally undermined the “best barrier against extremism,” it has been Sisi.

Yet Macron endorses his “friend”―his term―, who was defense minister when Egyptian forces killed 817 protestors in less than 12 hours in the 2013 Raba’a massacre, as a “partner in the fight against terrorism.” Beyond Raba’a, for which there has not been any accountability, the Sisi administration has routinely presided over the mass execution, enforced disappearance, and generalized torture of dissidents since overthrowing the democratically elected Mohamed Morsi government.

This latest evidence of “relativism” à la Macron could scarcely have been more ill-timed, coming on the very day that the EU finally agreed on a Global Human Rights Sanctions regime targeting perpetrators of serious human rights abuses. Instead of calling to account a persistent rights abuser, Macron rolled out the red carpet and decorated Sisi with the Grand Cross of the Legion of Honor (Légion d’honneur), the highest order of merit in France. Moreover, in unequivocally stating that France will not condition arms sales to Egypt due to human rights concerns, Macron also blatantly undermines the EU code of conduct on arms sales and neuters a significant lever on Egypt.

The case of Egypt is indicative of how France is apparently ready to walk away from the pledge it signed on to as an incoming member of the Human Rights Council: to address human rights concerns on their merits and to take leadership and responsibility in initiating action when necessary. The dire human rights situation in Egypt is unquestionably one that merits attention and action by the Council.

If Macron is serious about human rights as a foreign policy priority, then France needs to quickly change its game, starting at the Human Rights Council. It should seize opportunities to lead scrutiny by the Council of particularly dire human rights situations, such as in Cambodia, China, Egypt, Philippines, Russia, Saudi Arabia, and Sri Lanka. It should draft joint statements and resolutions, employing unequivocal language and calling for Council scrutiny to ensure there is accountability. It should also work alongside its allies, both within the EU and beyond, in building core groups to support such scrutiny and accountability.

It should also leverage its far-from-negligible global presence and influence to build support for such actions and thus carry the day when the draft resolutions are challenged by the rights abusers. And finally, it should not lose a beat and start showing it has spine, and is genuine in its desire to improve respect for human rights, starting at the upcoming 46th session of the Council, which begins on February 22.

Macron is fond of enrobing himself as a “constant advocate” for human rights, at home and abroad, and repeating, like many of his predecessors in office, that France was the birthplace of human rights. Yet his actions, as epitomized by Sisi’s recent visit, are more often than not showing how empty his rhetorical commitments to human rights are.

Without such a major change in its game and a strict commitment to its pledge as an incoming Council member― and no matter how many lofty generic statements it may make on human rights going forward―, France risks disappointing as a Council member, and Macron, not Johnson, to be revealed as the emperor with no clothes.