“Our City Was Gone”

Russia’s Devastation of Mariupol, Ukraine

- Unlawful Attacks on Civilians and Civilian Objects

- Armed Conflict in Populated Areas

- Framework Governing Explosive Weapons in Populated Areas

- Attacks on Critical Infrastructure

- Attacks on Hospitals

- Evacuations and the Delivery of Humanitarian Aid

- Forcible Transfers of Civilians

III. Civilians Denied Access to Critical Infrastructure

- Electricity

- Water

- Natural Gas and Heating

- Telecommunications

- Hospitals

- Fire Stations

- Services in Mariupol Since May 2022

IV. Struggling to Survive in Shelters

- Fleeing During the Last Days of February

- Trapped in the City as Evacuation Efforts, Aid Deliveries Fail

- Attacks on Mariupol’s City Bus Depot

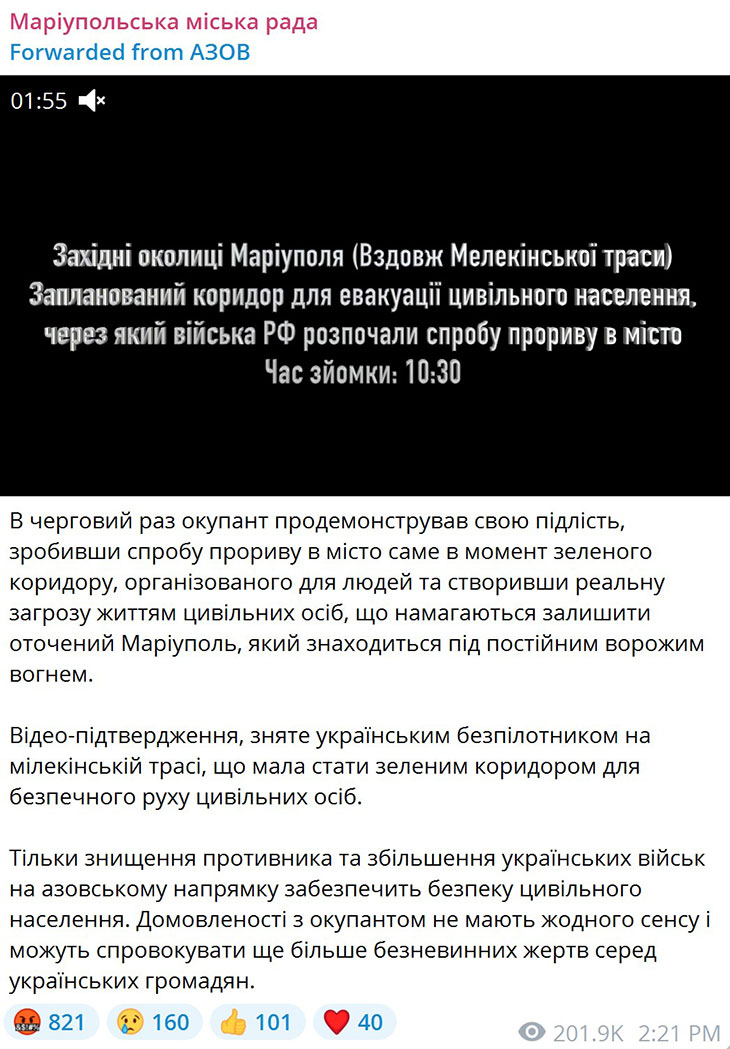

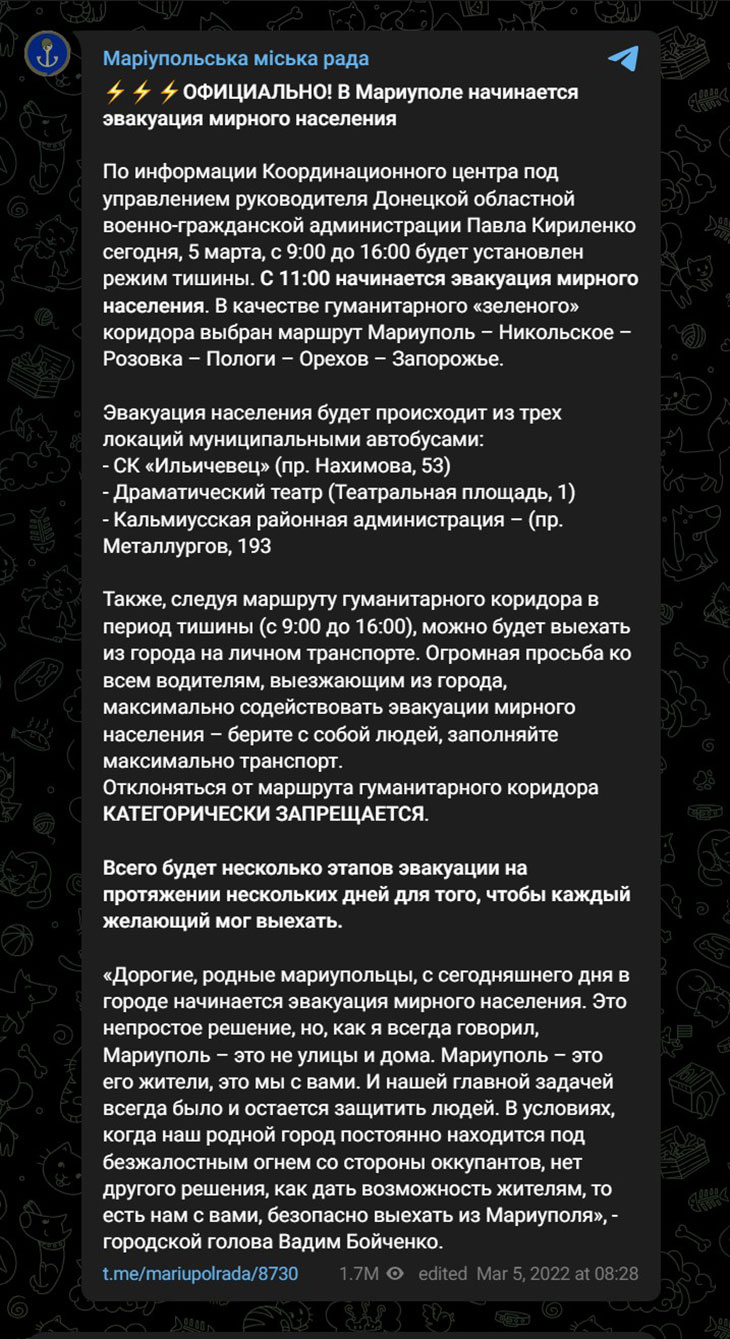

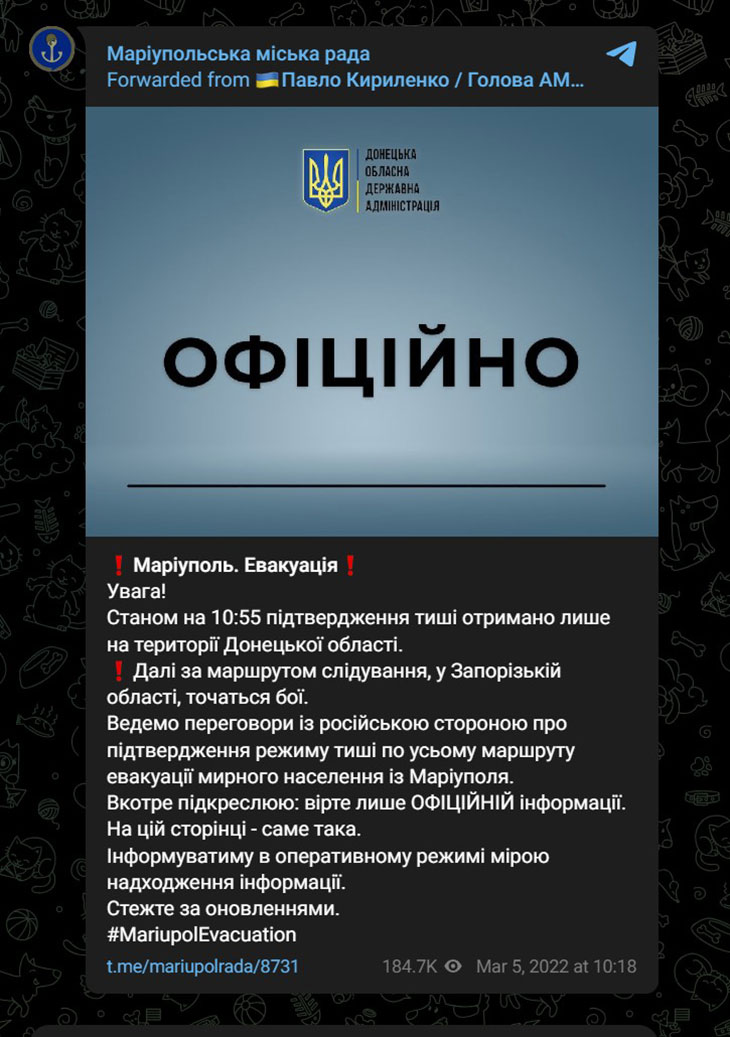

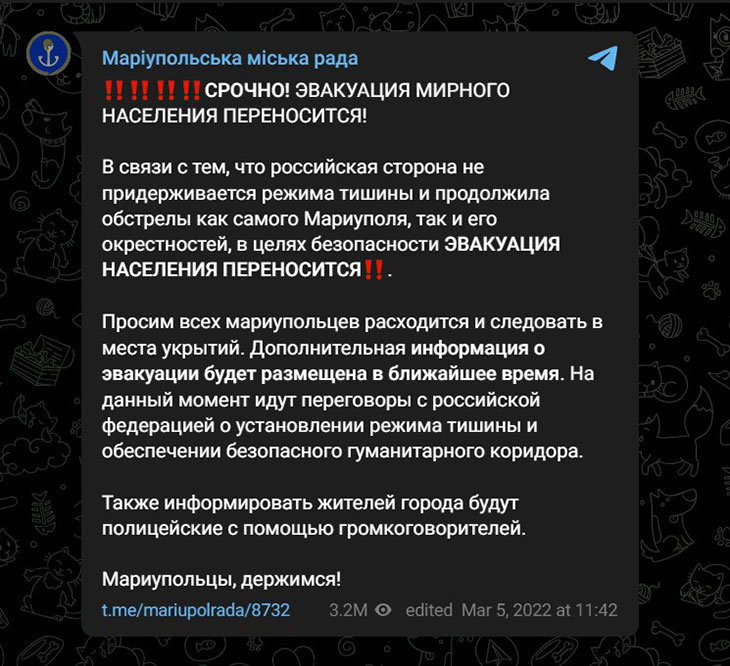

- Mariupol City Council Evacuation Announcements, March 5 to 8

- Ad Hoc Car Convoys Leaving the City After March 14

- Continued Efforts to Secure Official Evacuation Routes, Aid Delivery

- Forcible Transfers to Russia and Russia-Controlled Territory

VI. Extent of Damage to the City

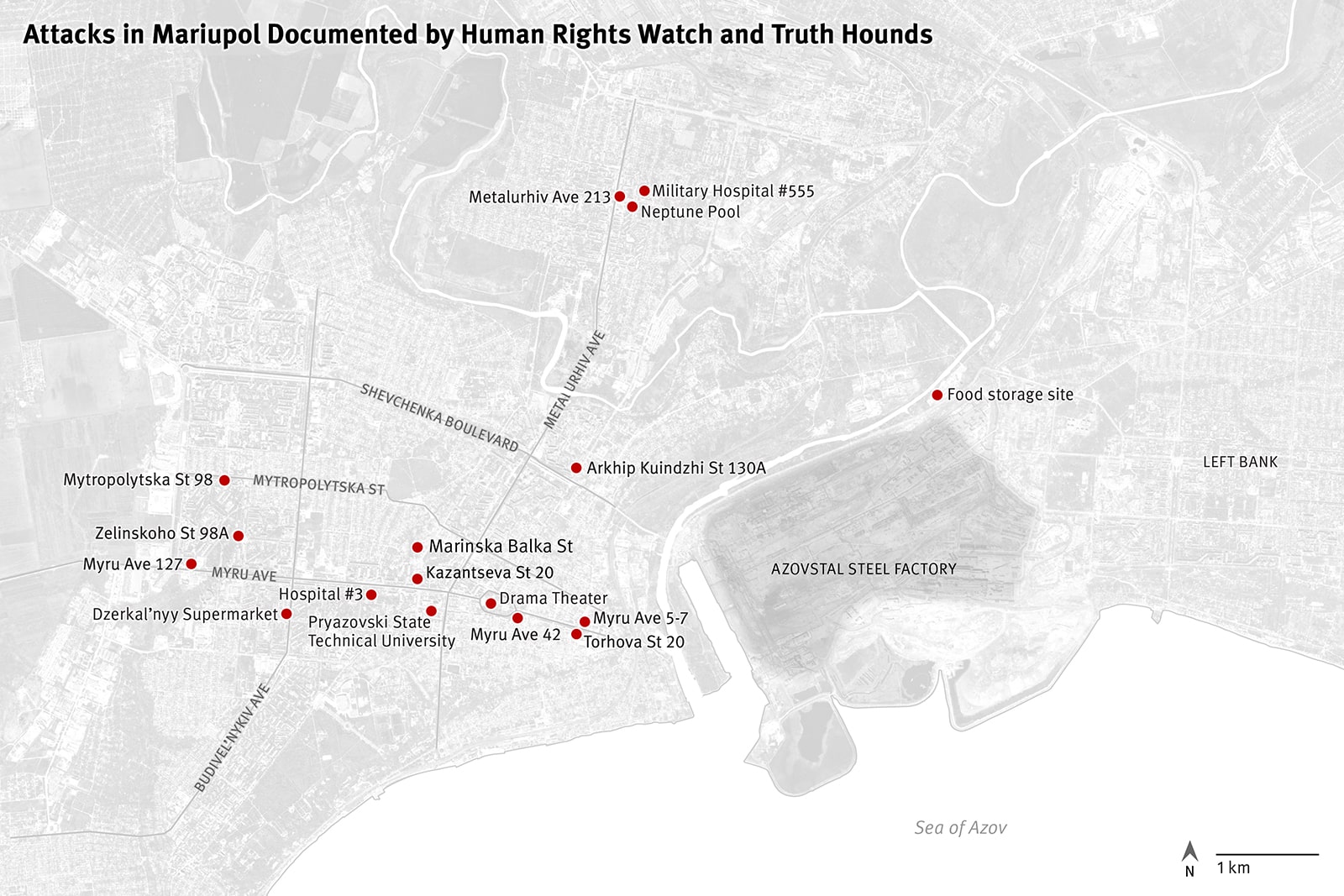

VII. Case Studies: Attacks Harming Civilians

- Food Storage Site North of the Azovstal Iron and Steel Works, March 1

- Torhova Street 20, March 8

- Hospital #3 and Pryazovskyi Technical University, March 9

- Zelinskoho Street 98A, March 9

- Marinska Balka Street 67 and Vidkryta Street 23, around midnight March 10-11

- Mytropolytska Street 98, March 11

- Dzerkalnyi Supermarket, Budivel’nykiv Avenue 86А, between March 4 and 13

- Myru Avenue 127, around March 13

- Shevchenka Lane 29a, March 13

- Shelter at Kazantseva Street 20, March 15

- Neptune Pool, Military Hospital #555 and Metalurhiv Avenue 213, March 16

- Donetsk Academic Regional Drama Theater, March 16

- Myru Avenue 42, March 22

- Arkhip Kuindzhi Street 130a, March 23

VIII. The Dead, Missing, and Injured

- Bodies Everywhere: Chaotic Burials at Start of Siege

- Deaths After the Battle

- How Occupying Forces Treated the Dead

- Counting the Dead: New Graves in Mariupol’s Cemeteries

- Identifying Those Who Died

- Tracing the Missing

- The Injured

IX. The Aftermath: Demolition, Reconstruction, Russification

- Command Structures of Russian and Russia-aligned Forces in Ukraine

- Specific Units and Commanders Involved in the Assault on Mariupol

- Methodology for Identifying Units and Commanders

- Details of Russian and Russia-affiliated Forces Identified in Mariupol

- Statements by Senior Russian Officials about the Assault on Mariupol

- Commanders Who May Bear Responsibility for Abuses in Mariupol

Summary

The story of Russia’s assault on Mariupol is one of horror.

On February 24, 2022, the day Russia began its all-out invasion of Ukraine, the Russian military and Russia-affiliated forces attacked Ukrainian armed forces defending the thriving city in southeastern Ukraine, home to iron and steel plants, a deep-water port, music and art festivals, and an iconic drama theater. Russian forces besieged Mariupol and, for eight weeks, hundreds of thousands of the city’s inhabitants faced devastation and death. Residents cowered in basements, living in fear of airstrikes, incessant shelling, and clashes between the armies. By mid-April, when Russian forces had almost full control of the city, thousands of civilians were dead and thousands of buildings, including high-rise apartments, hospitals, and schools, were damaged or lay in ruins. An estimated 400,000 residents had fled the city by mid-May, but those remaining were left for months without basic services, including electricity, running water, and health care.

This report is based on nearly two years of research conducted by Human Rights Watch and Truth Hounds, a leading Ukrainian human rights organization, as well as 3D reconstructions and visual and spatial analysis by SITU Research. We interviewed 240 people, mostly displaced Mariupol residents, and reviewed and analyzed dozens of satellite images and over 850 photos and videos. The report provides supporting documentation and complements our online feature, “Beneath the Rubble: Documenting Loss in Mariupol, a Ukrainian City Besieged and Devastated.”

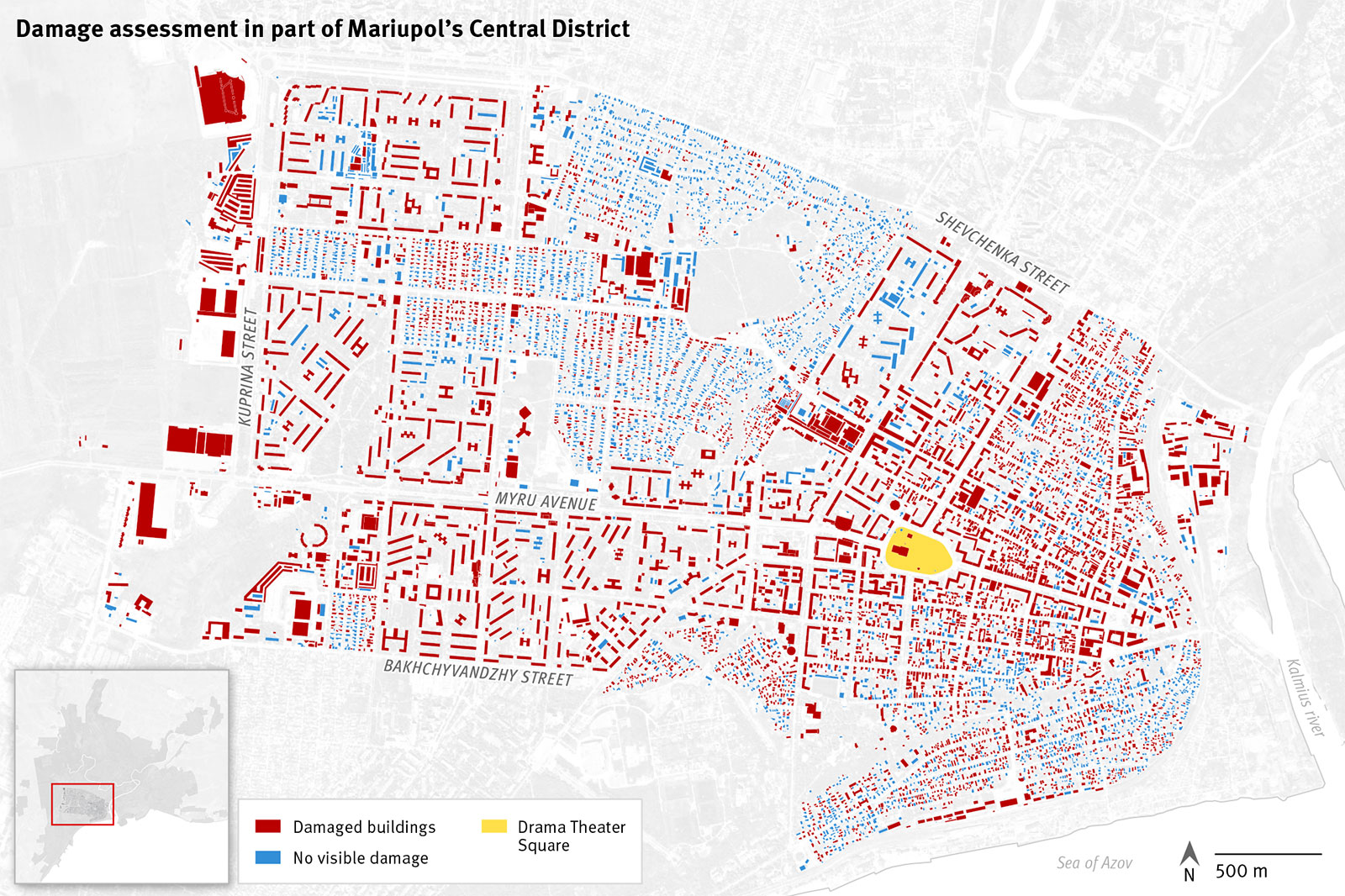

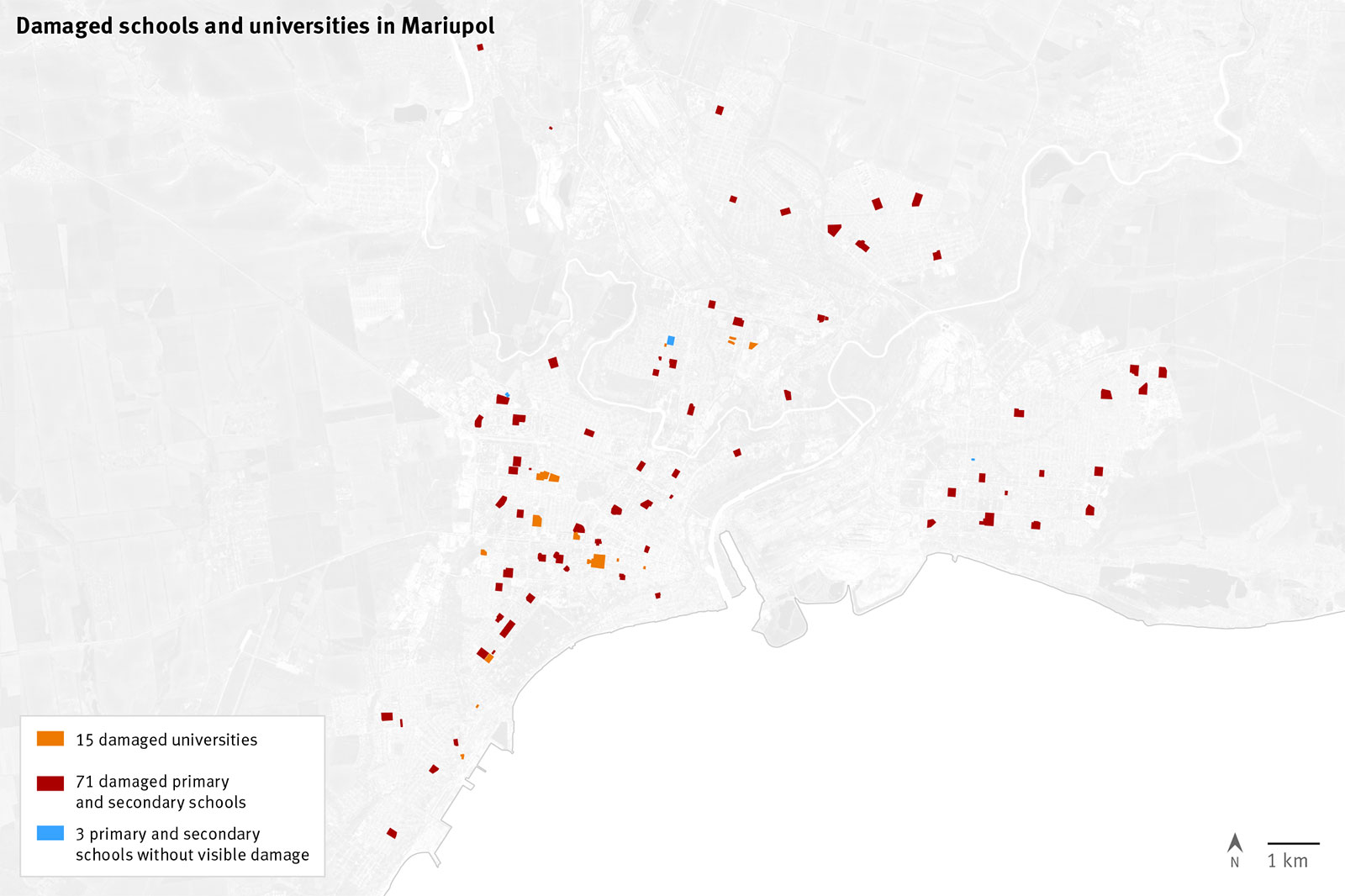

The report describes civilians’ lack of access to critical infrastructure and the struggles and risks they faced while sheltering in basements during the Russian assault on the city. It also outlines the repeated, largely unsuccessful attempts by Ukrainian authorities and volunteers, the United Nations (UN), and the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) to organize official evacuations and the delivery of humanitarian aid in the face of Russian intransigence. Our comprehensive building damage assessment found that, by mid-May 2022, 93 percent of the 477 multi-story apartment buildings in the central part of the city had been damaged. All 19 hospital campuses city-wide were damaged, and 86 of the 89 educational facilities that we identified across the city were also damaged.

We documented in detail 14 case studies covering 18 locations, many of which involved apparently unlawful Russian attacks, including attacks on two hospitals, the city’s famous drama theater, a food storage facility, an aid distribution site, a supermarket, and residential buildings serving as shelters. In each of these incidents, we found no evidence of a Ukrainian military presence in or near the building that was struck, which would have made the attack unlawfully indiscriminate. Or we found a limited military presence, which likely made the attack unlawfully disproportionate.

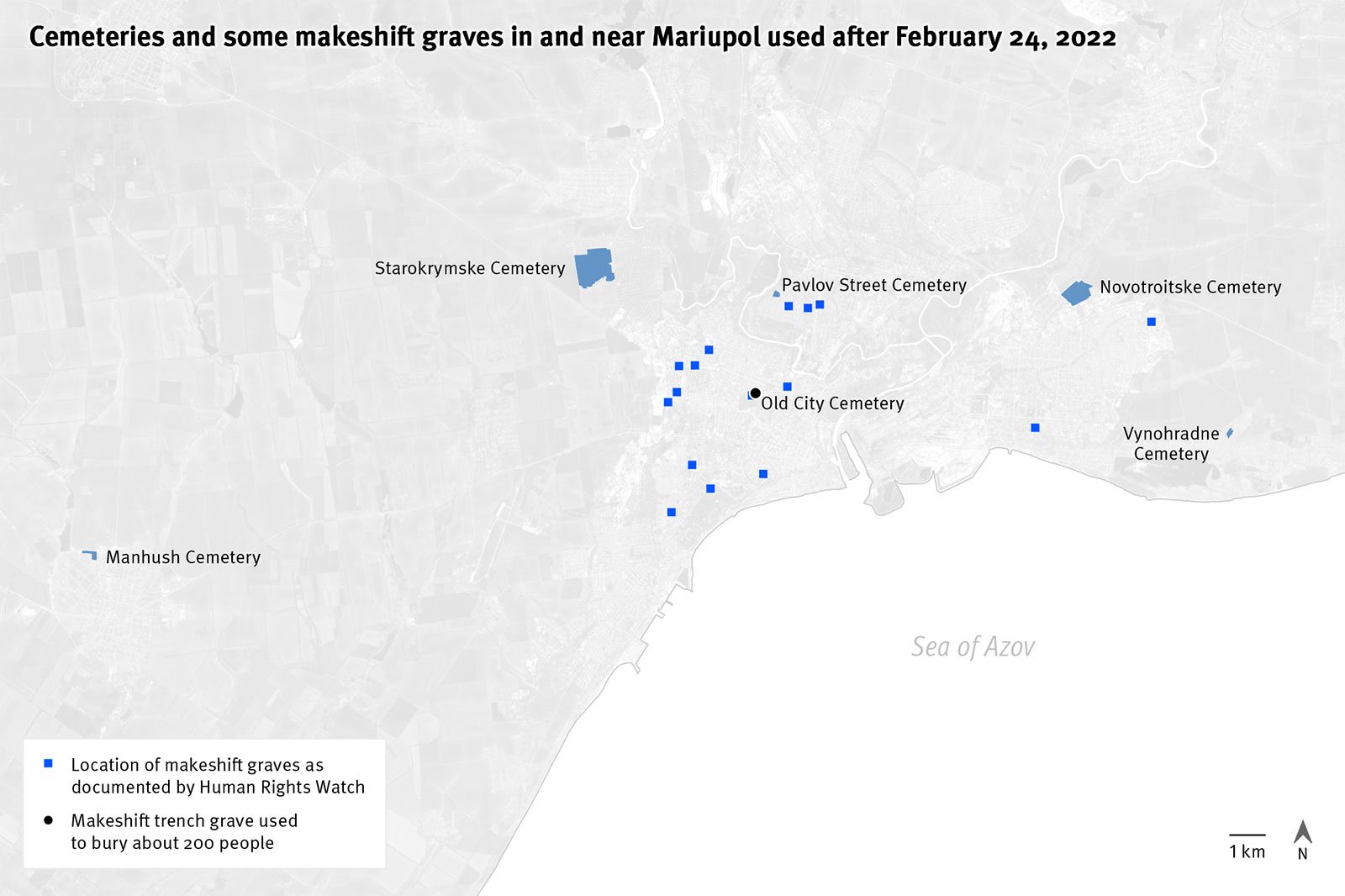

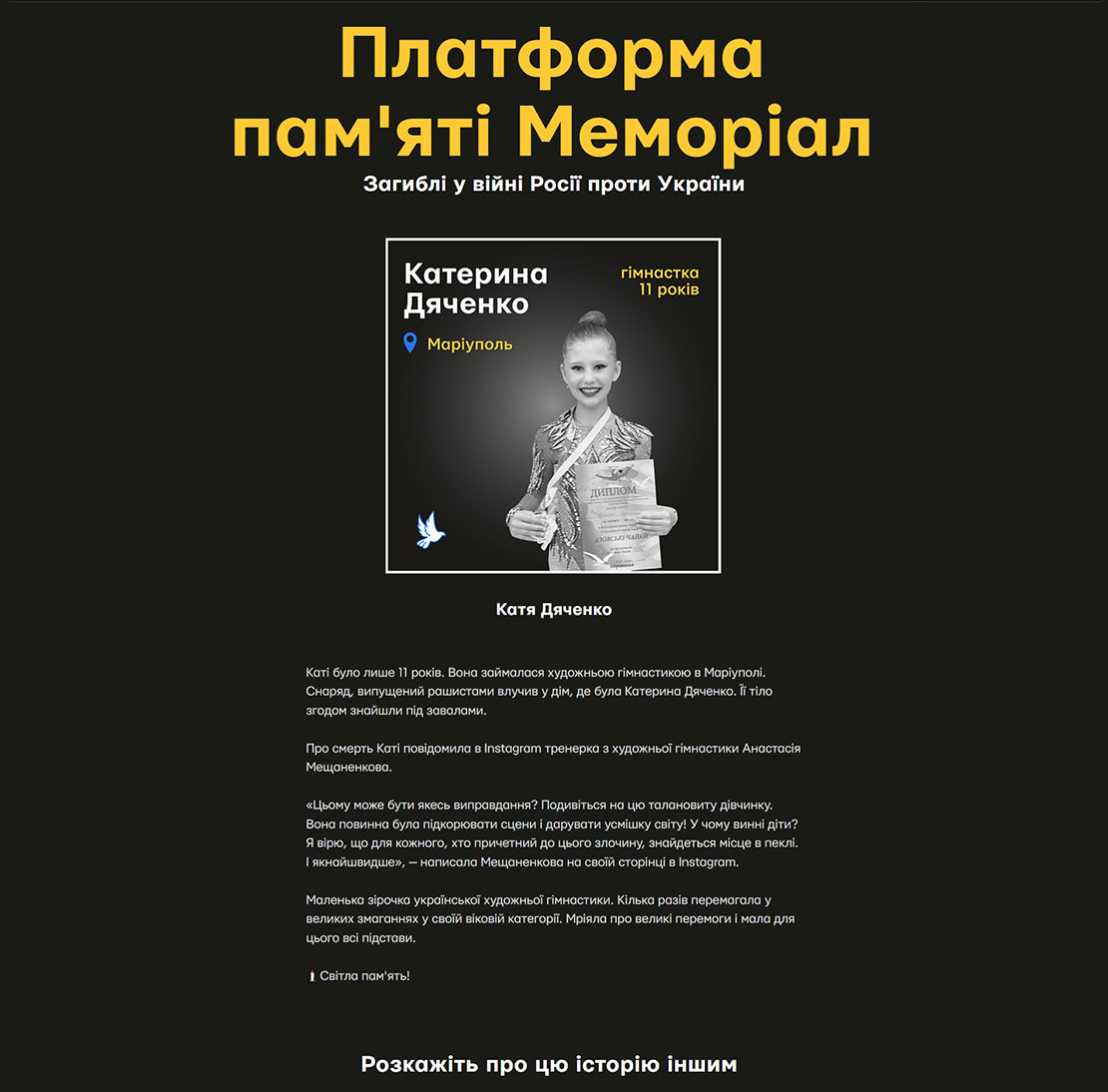

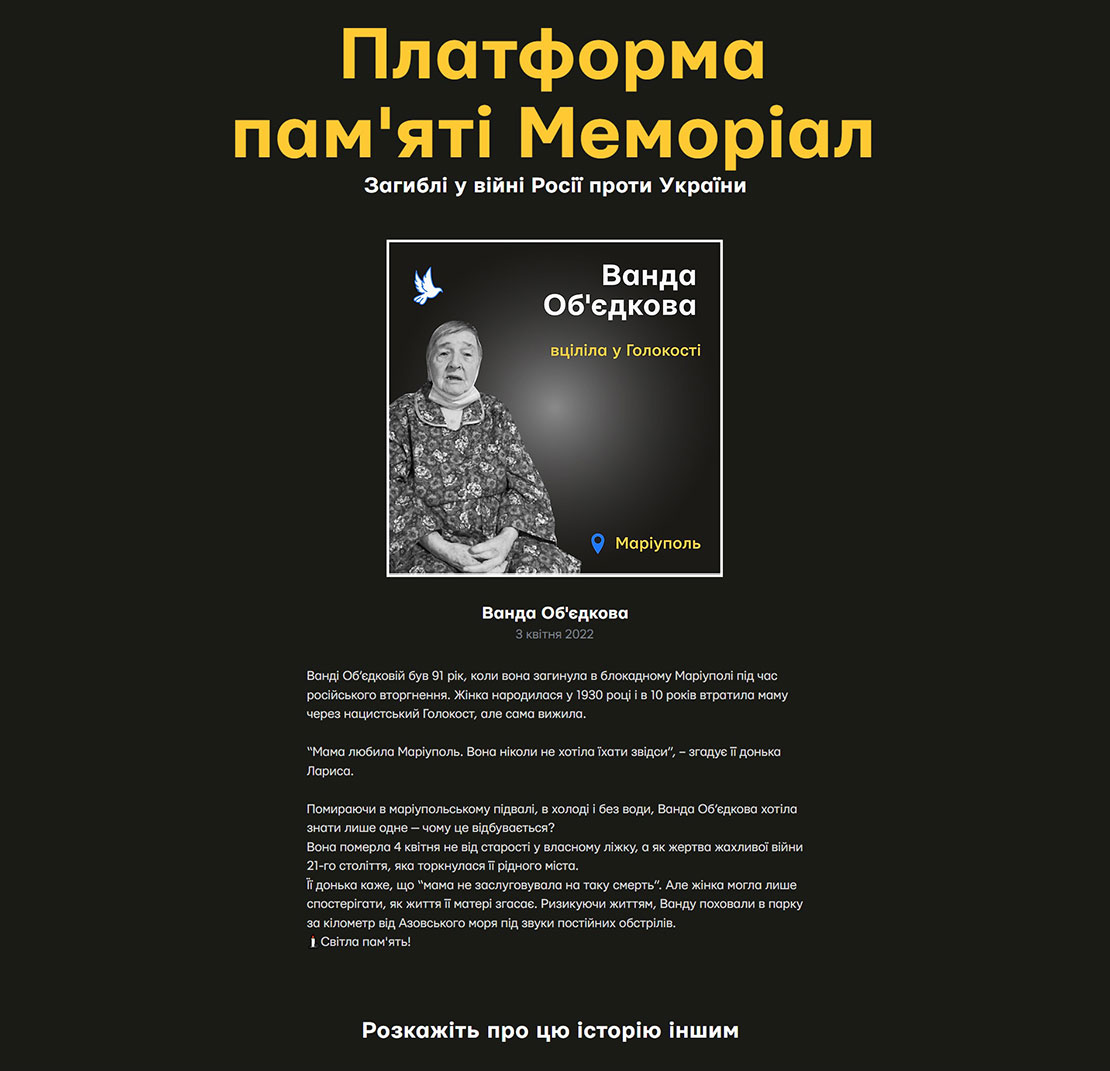

Our research found that thousands of civilians died during Russia’s siege and in the months that followed. Yet the full extent of those who died or were injured during the battle, or who remain missing, may never be known. Our assessment of satellite imagery and analysis of photos and videos of the city’s cemeteries that saw a significant increase in the number of graves shows that more than 10,000 people were buried in Mariupol between March 2022 and February 2023, of whom we estimate at least 8,000 likely died from war-related causes, whether direct attacks or from lack of health care or clean water.

These figures are based on an analysis of the graves in four of the city’s cemeteries and in Manhush town cemetery nearby and is likely a significant underestimation of the total number of dead. Many graves likely contained multiple bodies. The remains of others were likely buried in the rubble and taken away during demolition efforts. Some of those buried in makeshift graves may never have been transferred to the bigger cemeteries, and others either died or were buried outside of Mariupol. We were also not able to determine whether those buried in the city were civilians or military personnel, or how many died as a result of unlawful attacks.

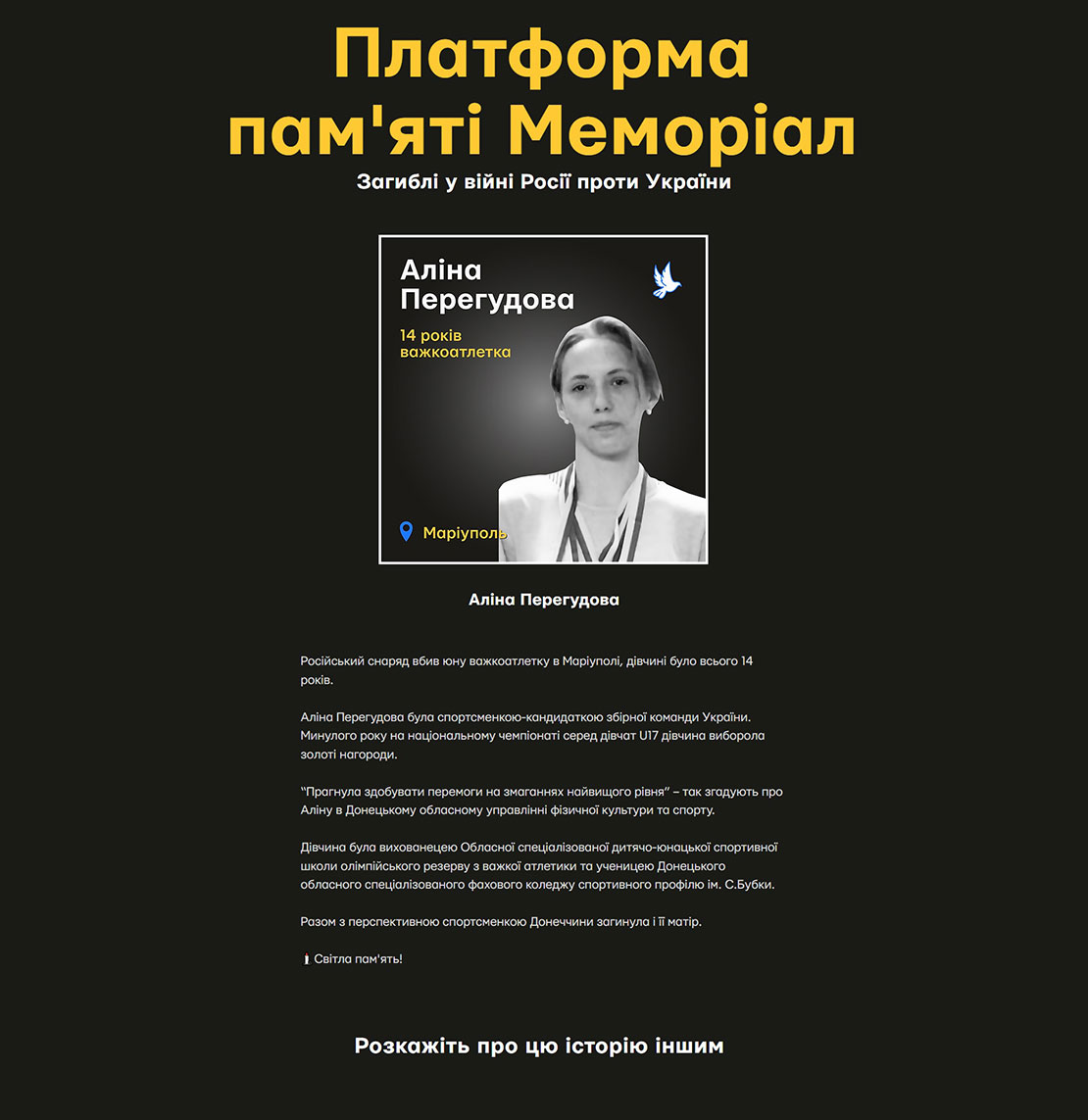

Behind each of the gravesites is a lifetime cut short, a story and, in many cases, a family that was never able to properly mourn or bury their loved one. Relatives of the missing posted information and inquiries on various online platforms; many are still waiting to learn of their fate. Thousands of others were injured during the siege, including those whose wounds were permanent.

Nearly two years since Russian forces captured and occupied Mariupol, the physical landscape of the city has changed profoundly. Damaged multi-story buildings have been demolished, together with countless irreplaceable personal items. Occupying forces have begun the process of building new high-rise apartments, part of Russia’s plans to complete the reconstruction of the city by 2025, and the further development of the city by 2035, if Russia still occupies it. Efforts to clear debris and bring down unsafe structures are consistent with an occupying forces’ obligations to ensure security for the population. However, by not creating the conditions to allow independent human rights investigators, forensic experts, and judicial officials to examine the damaged buildings before demolition, Russia effectively erased the physical evidence at hundreds of potential crime scenes across the city. This makes the digital damage assessment, 3D modeling, and other documentation in this project and others all the more necessary.

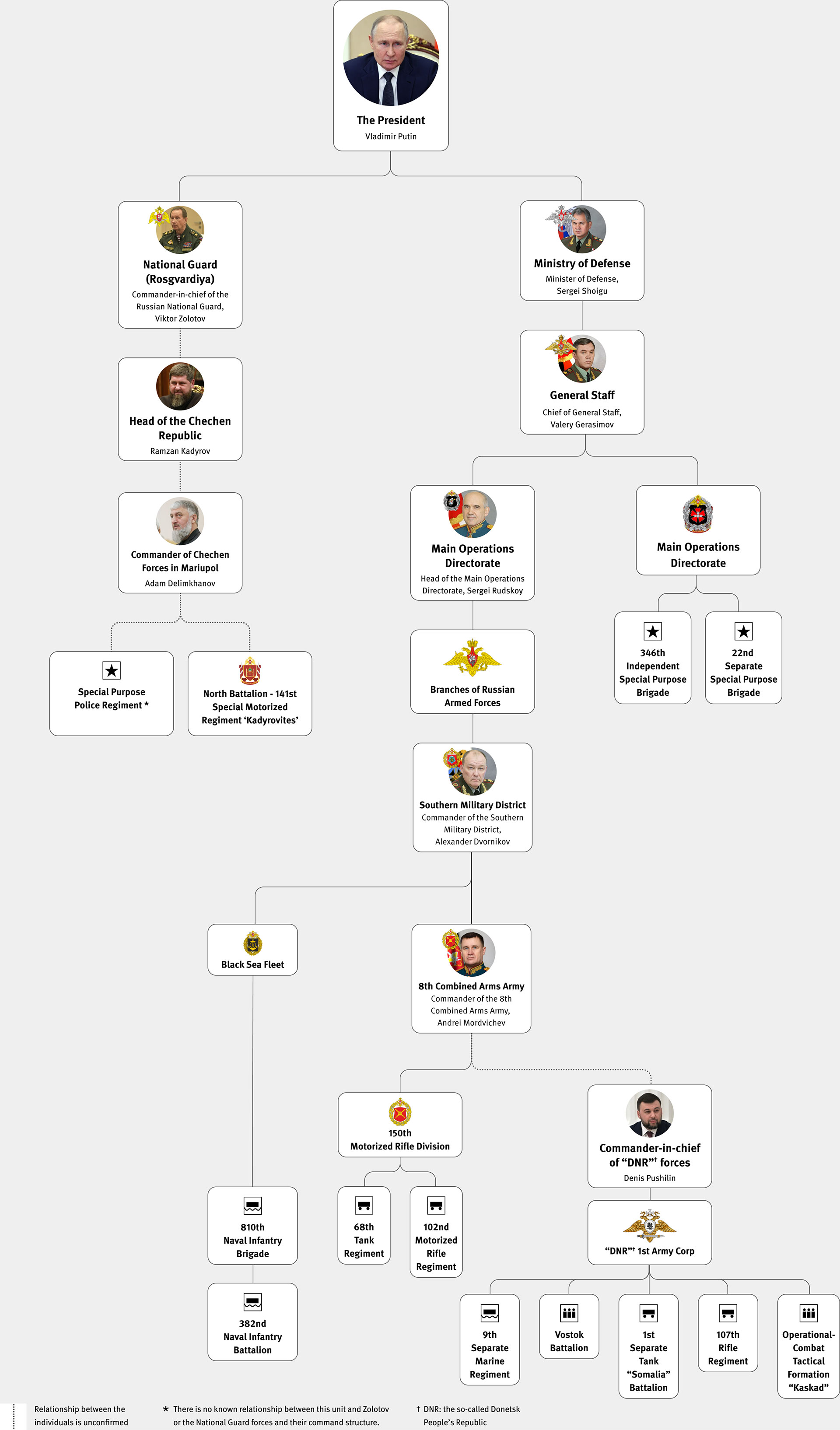

To identify the Russian commanders and military units that may have been responsible for laws-of-war violations in Mariupol that could amount to war crimes, we conducted an extensive review and analysis of Russian social media posts, obituaries of Russian personnel, Russian government and military statements, and photos and videos posted by or showing specific units present in Mariupol. We identified a total of 17 units of Russian and Russia-affiliated forces that were operating in the city in March and April 2022. We also concluded that the following 10 individuals may be responsible for war crimes in Mariupol as a matter of command responsibility:

-

Vladimir Putin, president of the Russian Federation and commander-in-chief of the military

-

Sergei Shoigu, defense minister and military second-in-command

-

Valery Gerasimov, first deputy defense minister and chief of the general staff of the armed forces

-

Sergei Rudskoy, first deputy chief of the General Staff of the Armed Forces and head of the Main Operations Directorate of the General Staff of the Armed Forces

-

Alexander Dvornikov, then-commander of the Southern Military District

-

Viktor Zolotov, commander-in-chief of the Russian National Guard

-

Andrei Mordvichev, commander of the 8th Combined Arms Army

-

Ramzan Kadyrov, head of the Chechen Republic and Chechen national guard forces

-

Adam Delimkhanov, commander of Chechen forces in Mariupol during the assault on the city

-

Denis Pushilin, head of the so-called Donetsk People’s Republic (DNR) and commander-in-chief of the armed groups organized under the DNR at the time of the assault on Mariupol

These individuals, and potentially other commanders of the 17 units identified in Mariupol, should be investigated and appropriately prosecuted for their alleged role in serious violations committed during the Russian forces’ assault. Reparations should also be paid to the victims and their families. Concerted international efforts towards justice and accountability are crucial to demonstrate that unlawful attacks carry consequences, to deter future atrocities, and to reinforce the principle that accountability for grave crimes cannot be eluded because of rank or position.

The battle for Mariupol has been among the most destructive of the war in Ukraine thus far. It left behind an unrecognizable wasteland of destroyed apartment buildings, charred streets, shells of cars and buses, and looted shops, with unknown numbers buried beneath the rubble. For months there was no functioning electricity, water, gas, or basic services such as hospitals and schools. By mid-2022, only an estimated fifth of the original population remained, living under Russian occupation.

In the nearly two years since the devastation of Mariupol and loss of civilian life from heavy weapons, other smaller cities and towns in Ukraine have endured similar destruction. To help protect civilians affected by armed conflicts in Ukraine and around the world, all countries should join and abide by the international Political Declaration on the Use of Explosive Weapons in Populated Areas. They should condemn and seek to end all use of explosive weapons with wide area effects in cities, towns, and villages – no matter where or by whom.

DOWNLOAD THE SUMMARY IN ARABIC, CHINESE (SIMPLIFIED), CHINESE (TRADITIONAL), FRENCH,

GERMAN, HINDI, PORTUGUESE, AND SPANISH.

Methodology

For this report and the accompanying web feature, Human Rights Watch and Truth Hounds—a leading Ukrainian human rights organization—interviewed 240 people. Of these, 26 were Mariupol city officials and volunteers, 11 were healthcare workers in Mariupol, 168 were other Mariupol residents, 7 were national Ukrainian government officials, and 28 were interviewed in other capacities, including volunteers based outside of Mariupol, infrastructure company staff living outside of Mariupol, international and Ukrainian humanitarian staff, Ukrainian and international human rights officials and activists, experts on the Russian military, and Ukrainian and international journalists who reported on Mariupol.

On December 4, 2023, we sent the Russian government a summary of our findings and a list of questions. At time of writing, we had not received a response.

Human Rights Watch and Truth Hounds were unable to visit Mariupol due to the fighting and subsequent occupation of the city, which prevented us from being able to safely conduct interviews in person without undue risk of reprisals against those we spoke to. Instead, we interviewed displaced residents in person or by phone between March 2022 and January 2024.

Nearly all interviews were conducted in Ukrainian, with some conducted in Russian and English. Researchers informed all interviewees about the purpose and voluntary nature of the interviews, and the ways in which we would use the information. We obtained informed consent from all interviewees, who understood they would receive no compensation for their participation. For reasons of personal security, we have withheld the names and identifying information of some of the individuals featured in the report to ensure their anonymity and have given them pseudonyms.

Human Rights Watch analyzed dozens of high and very high-resolution commercial satellite images of the locations where attacks documented in this report occurred and damage done to other parts of the city. Open source research by Human Rights Watch, Truth Hounds, and SITU Research also involved analyzing photographs and videos that were shared directly with researchers or collected from social media platforms, including Facebook, Instagram, Telegram, TikTok, X (formerly known as Twitter), VK, and YouTube. We verified these photographs and videos, geolocated them to Mariupol, and determined the time period in which they were recorded. In total, this report and the accompanying web feature use 850 photographs and videos captured between February 24, 2022, and June 17, 2023.

By matching landmarks in the videos with satellite imagery, street-level photographs, or other visual material, and comparing this with accounts from witnesses, we determined the location and approximate time and date of the specific attacks mentioned in the case study chapter. We also studied the imagery to determine the types of weapons used during some of those attacks and more generally during the assault on the city. Some of these images were used to help us photogrammetrically reconstruct 3D models of seven buildings mentioned in the case studies in the report. The 3D reconstructions demonstrate the state of these buildings before and after the attacks. The 3D reconstructions were also a helpful tool when conducting interviews as they allowed witnesses to describe or point out very specific locations when describing an attack, and to give us more specific details about what they saw.

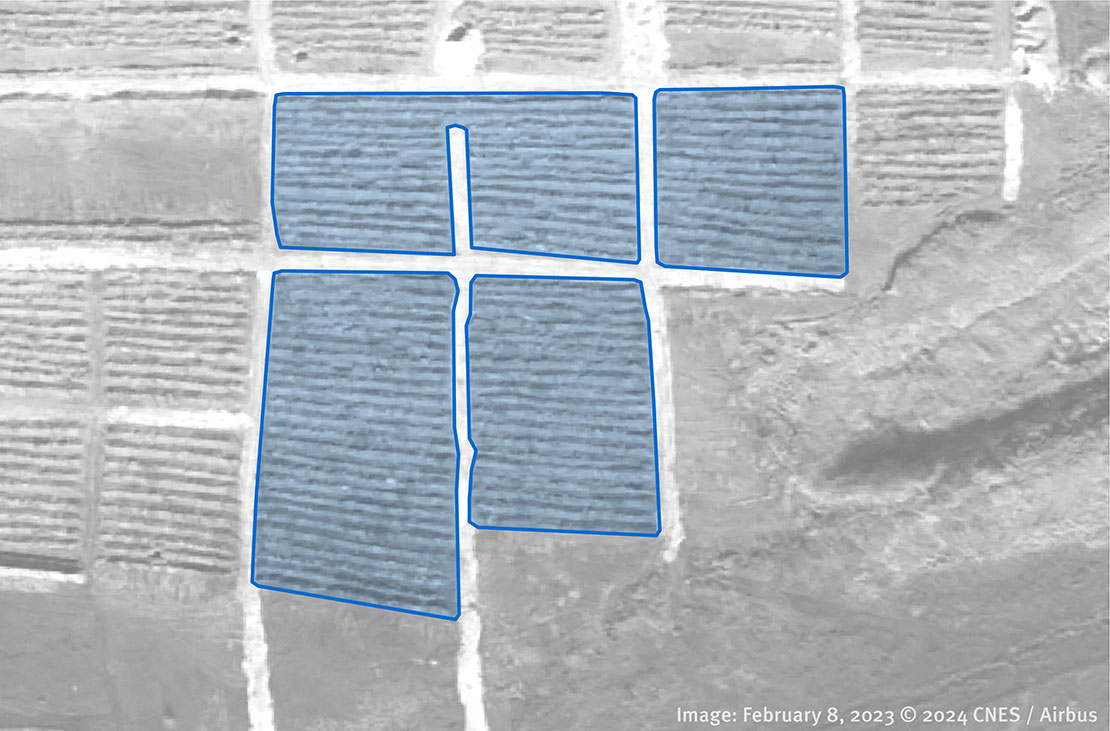

For the damage assessment and demolitions, we identified a 14-square-kilometer area of focus in the center of the city, where most of the buildings for which we obtained detailed accounts from witnesses of attacks are located. This area does not follow any specific district or city boundaries but is demarcated by major roads to the north and south of Myru Avenue (see image below). To analyze the extent of damage and demolition in at least part of the city in more detail, we restricted our assessment to buildings in this area.

To determine the damage to civilian infrastructure inside Mariupol’s city boundaries, including hospitals, schools, and universities, we analyzed high and very high-resolution commercial satellite images.

To obtain a rough estimate of the minimum number of bodies that were buried in and around Mariupol between March 2022 and February 2023, we used very high-resolution commercial satellite images and drone footage to assess the gravesites at five cemeteries that saw a significant increase in the number of graves and that contain both individual graves and trench-type graves.

To identify the Russian commanders and military units that may bear responsibility for the violations documented in this report, we reviewed social media posts by Russian soldiers present in Mariupol or involved in the assault; obituaries of Russian military personnel killed in Mariupol; awards given to Russian military commanders for their “service” in Mariupol; other public statements by Russian government and military officials; and Russian media reports.

Chapter I Applicable Legal Standards

Russian and Russia-affiliated forces conducting military operations against Ukrainian forces in their assault on Mariupol committed numerous apparent violations of international humanitarian law, or the laws of war. Violations include deliberate or indiscriminate air and ground attacks on civilian objects, including on a hospital, that killed and injured numerous civilians; an apparently unlawful strike hitting part of the electricity infrastructure; the apparent blocking of civilian evacuations and the arbitrary denial of humanitarian aid; and the forced transfers of Ukrainian citizens to Russia and Russian-occupied territory.

War crimes are serious violations of the laws of war committed by individuals with criminal intent.1 Those who order, carry out or are responsible as a matter of command responsibility may be found liable for war crimes.2 States are obligated to investigate alleged war crimes committed by their nationals or armed forces, or on their territory.3

Crimes against humanity are certain crimes committed by members of government armed forces or non-state armed groups that are knowingly committed as part of a widespread or systematic attack on a specific civilian population. Relevant crimes include murder, torture, deportation, or other inhumane acts of a similar character intentionally causing great suffering, or serious injury to body or to mental or physical health.4

Many of the unlawful strikes on Mariupol civilian structures may amount to war crimes, including the attack on the Mariupol Drama Theater. The forced deportations of Ukrainians to Russia and forced transfers to other areas occupied by Russia is also a war crime and a potential crime against humanity. War crimes investigations are needed with respect to other attacks on civilian buildings and critical infrastructure, and the blocking of humanitarian aid and evacuations of Ukrainian civilians.

The war between Russia and Ukraine constitutes an international armed conflict, governed by international humanitarian treaty law - primarily the four Geneva Conventions of 19495 and its First Additional Protocol of 1977 (Protocol I),6 as well as the rules of customary international humanitarian law.7 Both Russia and Ukraine are parties to the 1949 Geneva Conventions and Protocol I.

The laws of war provide protections to civilians and other noncombatants from the hazards of armed conflict. They also address the conduct of hostilities-the means and methods of warfare-by all sides to a conflict. Foremost is the rule that parties to a conflict must distinguish at all times between combatants and civilians. Civilians may never be the deliberate target of attacks. Parties to the conflict are required to take all feasible precautions to minimize harm to civilians and civilian objects and to refrain from attacks that fail to discriminate between combatants and civilians, or that would cause disproportionate harm to the civilian population.8

Individuals who commit serious violations of the laws of war with criminal intent-that is, deliberately or recklessly-can be held liable for war crimes.9 Commanders who knew or should have known about abuses by their forces and failed to stop them or punish those responsible can be prosecuted as a matter of command responsibility.10

Populations also remain protected by international human rights law, notably the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights11 and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.12 The destruction and damage to the civilian infrastructure, including healthcare facilities, schools, and markets, threatens the enjoyment of basic rights such as the right to health, education, and an adequate standard of living, including food, housing, and water.

Unlawful Attacks on Civilians and Civilian Objects

The two fundamental tenets of international humanitarian law are those of “civilian immunity” and “distinction.”13 They impose a duty, at all times during the conflict, to distinguish between combatants and civilians, and to target only the former. While the laws of war recognize that some civilian casualties are inevitable, parties to a conflict may not target civilians and civilian objects and may direct their operations against only military objectives.

Military objectives are anything that by their nature, location, purpose, or use provides enemy forces a definite military advantage in the circumstances prevailing at the time.14 Combatants, weapons, ammunition, and materiel are military objectives. In general the law prohibits direct attacks against what are by their nature civilian objects, such as homes and apartments, shops, places of worship, hospitals, schools, and cultural monuments, unless they are being used for military purposes.15 Even though a residential home is presumed to be a civilian object, for example, its use by enemy soldiers to deploy or to store weaponry, renders it a military objective and subject to attack for the duration of that use. Hospitals and other medical facilities have special additional protection under the laws of war.

International humanitarian law prohibits indiscriminate and disproportionate attacks. Indiscriminate attacks are those that strike military objectives and civilians or civilian objects without distinction. Examples of indiscriminate attacks are attacks that are not directed at a specific military objective or that use weapons that cannot be directed at a specific military objective.16

Prohibited indiscriminate attacks include area bombardment, which are attacks by artillery or other means that treat as a single military objective a number of clearly separated and distinct military objectives located in an area containing a concentration of civilians and civilian objects. Military commanders must choose a means of attack that can be directed at military targets and will minimize incidental harm to civilians. If the weapons used are so inaccurate that they cannot be directed at military targets without imposing a substantial risk of civilian harm, such as Grad rockets, then they should not be deployed. Anti-personnel landmines and cluster munitions are prohibited by international treaty and should never be used because they are inherently indiscriminate.17

Attacks that violate the principle of proportionality are also prohibited. An attack is disproportionate if it may be expected to cause incidental loss of civilian life or damage to civilian objects that would be excessive in relation to the concrete and direct military advantage anticipated at the time of the attack.18

Armed Conflict in Populated Areas

The laws of war do not prohibit fighting in urban areas, although the presence of many civilians places greater obligations on parties to the conflict to take steps to minimize harm to civilians. Parties to a conflict must take constant care during military operations to spare the civilian population and to “take all feasible precautions” to avoid or minimize the incidental loss of civilian life and damage to civilian objects. These precautions include doing everything feasible to verify that the objects of attack are military objectives and not civilians or civilian objects, and giving “effective advance warning” of attacks when circumstances permit.19

Warring parties must also take all feasible measures to minimize the risk to civilians under their control. Forces deployed in populated areas must avoid locating military objectives near densely populated areas and endeavor to remove civilians from the vicinity of military activities.20 Belligerents are prohibited from using civilians to shield military objectives or operations from attack.21

The attacking party is not relieved of its obligation to take into account the risk to civilians simply because it considers the defending party responsible for locating legitimate military targets within or near populated areas.

Framework Governing Explosive Weapons in Populated Areas

The use of explosive weapons in populated areas poses one of the gravest threats to civilians in contemporary armed conflict.22 While there is no specific prohibition against the use of explosive weapons in populated areas, their use in such areas heightens concerns of unlawfully indiscriminate and disproportionate attacks. Explosive weapons include a range of conventional air-dropped and surface-fired weapons, including certain air-delivered bombs, cluster munitions, missiles, unguided rockets, multi-barrel rocket launchers, and large-caliber artillery and mortar projectiles. They can deliver multiple munitions simultaneously that saturate a large area, have a large destructive radius, spread fragments widely, and are inherently inaccurate.

Such weapons kill and injure civilians at the time of attack, either directly, due to the weapons’ blast and fragmentation, or indirectly, as a result of fires, flying debris, or collapsing buildings. They also have long-term ripple, or “reverberating,” effects, including severe psychological harm. They damage civilian buildings, including homes and businesses, and civilian infrastructure such as power plants, healthcare and educational facilities and water and sanitation systems, which in turn interferes with basic services such as health care and education, infringing on human rights. They cause environmental damage and displace communities.

Several types of weapons and weapon delivery systems, both manufactured and improvised, are inherently difficult to use in populated areas without a substantial risk of indiscriminate attack. Weapons such as mortars, artillery, and rockets, such as Grad rockets, when firing unguided munitions, are fundamentally inaccurate systems. In some cases, armed forces can compensate by observing impacts and making adjustments, but the initial impacts and the relatively large area over which these weapons could strike regardless of adjustments make them unsuitable for use in populated areas.

As of December 2023, 83 countries have adopted the “Declaration on the Protection of Civilians from the Use of Explosive Weapons in Populated Areas,” which seeks to better protect civilians from the use of explosive weapons in populated areas.23 The declaration urges compliance with the laws of war but also commits its signatories to adopt policies and practices to restrict or refrain from the use of explosive weapons in populated areas when harm to civilians or civilian objects is expected, including by taking direct and indirect effects into account when planning and executing attacks, and by assisting victims. While the declaration is not legally binding, countries that endorse it commit to take steps to advance the protection of civilians from explosive weapons that go beyond existing law.

Attacks on Critical Infrastructure

Sieges directed at enemy forces and for the purpose of capturing an enemy-controlled area are permitted under the laws of war as a legitimate military objective. However, siege tactics cannot include destroying, removing, or rendering useless objects indispensable to the civilian population’s survival. Deliberate employment of such tactics, with the intent of starving the civilian population or forcing them to leave the city, violate the laws of war.24 It may also amount to inhumane treatment of the civilian population, a crime against humanity.25 Tactics that arbitrarily deny civilians access to items essential for their well-being such as water, food, and medicine are also prohibited.

Some critical infrastructure, such as electricity generation plants, water infrastructure, and telecommunications facilities, are considered dual-use objects, entities that normally have both civilian and military purposes.26 A dual-use object is a legitimate military target if it is used in a way that makes an “effective contribution to military action” and its partial or total destruction, capture or neutralization in the circumstances ruling at the time offers “a definite military advantage.” An attack on a dual-use object that is a legitimate military objective still must consider the principle of proportionality.27 This means that attacking forces should verify at all times that the risks to the civilian population from any such attack-that is, the extreme importance of those facilities to the civilian population and the anticipated impact of their destruction-do not outweigh the anticipated military benefit.

The attacking force should also assess whether an attack on other military objectives causing less damage to civilian lives and objects would offer the same military advantage.

Attacks on Hospitals

Hospitals, clinics, medical centers, and similar facilities, whether civilian or military, are considered to be medical units that have special protections under the laws of war. While other presumptively civilian structures become military objectives if they are being used for a military purpose, hospitals lose their protection from attack only if they are being used, outside their humanitarian function, to commit “acts harmful to the enemy.”28

Several types of acts do not constitute “acts harmful to the enemy,” such as the presence of armed guards, or when small arms from the wounded are found in the hospital. Even if military forces misuse a hospital to store weapons or shelter able-bodied combatants, the attacking force must issue a warning to cease this misuse, setting a reasonable time limit for it to end, and attacking only after such a warning has gone unheeded.29

Under the laws of war, doctors, nurses, and other medical personnel must be permitted to do their work and be protected in all circumstances. They lose their protection only if they commit, outside their humanitarian function, acts harmful to the enemy.30

In May 2016, the UN Security Council unanimously expressed deep concern about the increase in the number of attacks and threats against medical facilities and personnel in resolution 2286 and urged countries around the world to take measures to prevent future attacks. The resolution also strongly condemned what it called the “prevailing impunity for violations and abuses committed against medical personnel and humanitarian personnel exclusively engaged in medical duties, their means of transport and equipment, as well as hospitals and other medical facilities in armed conflict.” It noted that this impunity may in turn contribute to the “recurrence of these acts.”31

The resolution strongly urged states to “conduct, in an independent manner, full, prompt, impartial and effective investigations within their jurisdiction of [relevant] violations of international humanitarian law … and, where appropriate, take action against those responsible in accordance with domestic and international law, with a view to reinforcing preventive measures, ensuring accountability and addressing the grievances of victims.”32

Evacuations and the Delivery of Humanitarian Aid

The laws of war do not prohibit sieges by land of enemy forces so long as they do not cause disproportionate harm to civilians. They require parties to a conflict to facilitate the evacuation of civilians who want to leave conflict areas and not to arbitrarily prevent them from doing so. Whether or not the parties establish humanitarian corridors, they remain responsible for taking all feasible precautions to minimize the harm to civilians from the effects of attacks. Parties should allow access for neutral humanitarian actors to support civilians at risk who may need assistance to leave, including people with injuries, chronic or severe medical conditions, people with disabilities, older people, pregnant people and those who have recently given birth, and children.

International humanitarian law requires warring parties not to withhold consent for relief operations on arbitrary grounds and to allow and facilitate rapid and unimpeded impartial aid to civilians in need. They may take steps to control the content and delivery of humanitarian aid, such as to ensure that consignments do not include weapons. However, deliberately impeding relief supplies is prohibited. Lawful military restrictions on aid cannot have a disproportionate effect on the civilian population.33

Forcible Transfers of Civilians

Parties to an international armed conflict are prohibited under the laws of war from forcibly transferring inside the country or deporting outside the country the civilian population of an occupied territory, in whole or in part. Violation of this prohibition is a grave breach of the Geneva Conventions and prosecutable as a war crime and a crime against humanity.34 Provisions in the Fourth Geneva Convention and Protocol I, prohibiting individual or mass forcible transfers are clear that the prohibition is regardless of motive.35

To constitute the crime of deportation or transfer, the transfer needs to be “forcible.” Consent to be moved has to be voluntary and genuine, and not given under coercive conditions. As the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) made clear, the absence of genuine choice making displacement unlawful and forcible can include psychological force caused by “fear of violence, duress, detention, psychological oppression or abuse of power,…or by taking advantage of a coercive environment.”36 Therefore, a transfer is not voluntary if civilians agree or seek to be transferred as the only means to escape risk of abuse if they remain. Moreover, transferring or displacing civilians is not justified or lawful as being on humanitarian grounds if the humanitarian crisis triggering the displacement is itself the result of unlawful activity by those in charge of the transfers.37

Warring parties may temporarily displace or evacuate civilians to protect them from the effects of an attack, or if civilian security or imperative military reasons demand such displacement. Protocol I requires that parties to the conflict, “to the maximum extent feasible,” take the necessary precautions to protect civilians and civilian objects under their control from the dangers resulting from military operations, including seeking to remove civilians and civilian objects under their control from the vicinity of military targets.38 Those displaced or evacuated should be transferred back to their homes as soon as hostilities in the area in question have ceased.39

Chapter II The Taking of Mariupol

When Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022, Ukrainian forces in the city of Mariupol, on the northern coast of the Sea of Azov in southeastern Ukraine, were among the first attacked.

Mariupol is the site of two of Ukraine’s largest iron and steel factories, the Ilyich Iron and Steel Works and the Azovstal Iron and Steel Works (Azovstal steel plant). Capturing Mariupol and areas to the west of the city would allow Russia to control a land corridor between the Crimean Peninsula about 200 kilometers to the west, occupied by Russia since 2014, and the Donbas region about 10 kilometers to the east. The Donbas region includes the self-proclaimed, Russia-backed “DNR” and most parts of “Luhansk People’s Republic” (LNR).40

Forces of the so-called DNR and LNR operating in these areas since 2014 were officially integrated into the Russian military in 2022. Capturing Mariupol would also mean control of about 80 percent of Ukraine’s Sea of Azov coastline and related trade: the city’s port was the largest in the Azov Sea region and a key export hub for Ukraine’s steel, coal, and corn.41

Until February 2022, about 540,000 people inhabited the city.42 Former residents and visitors described Mariupol’s distinctly Ukrainian character, its multicultural, multi-religious, and multilingual identity, and its recent development into a modern cultural hub, with a new public transport system, arts events such as Gogol Fest, and its popularity as a summer seaside destination.43

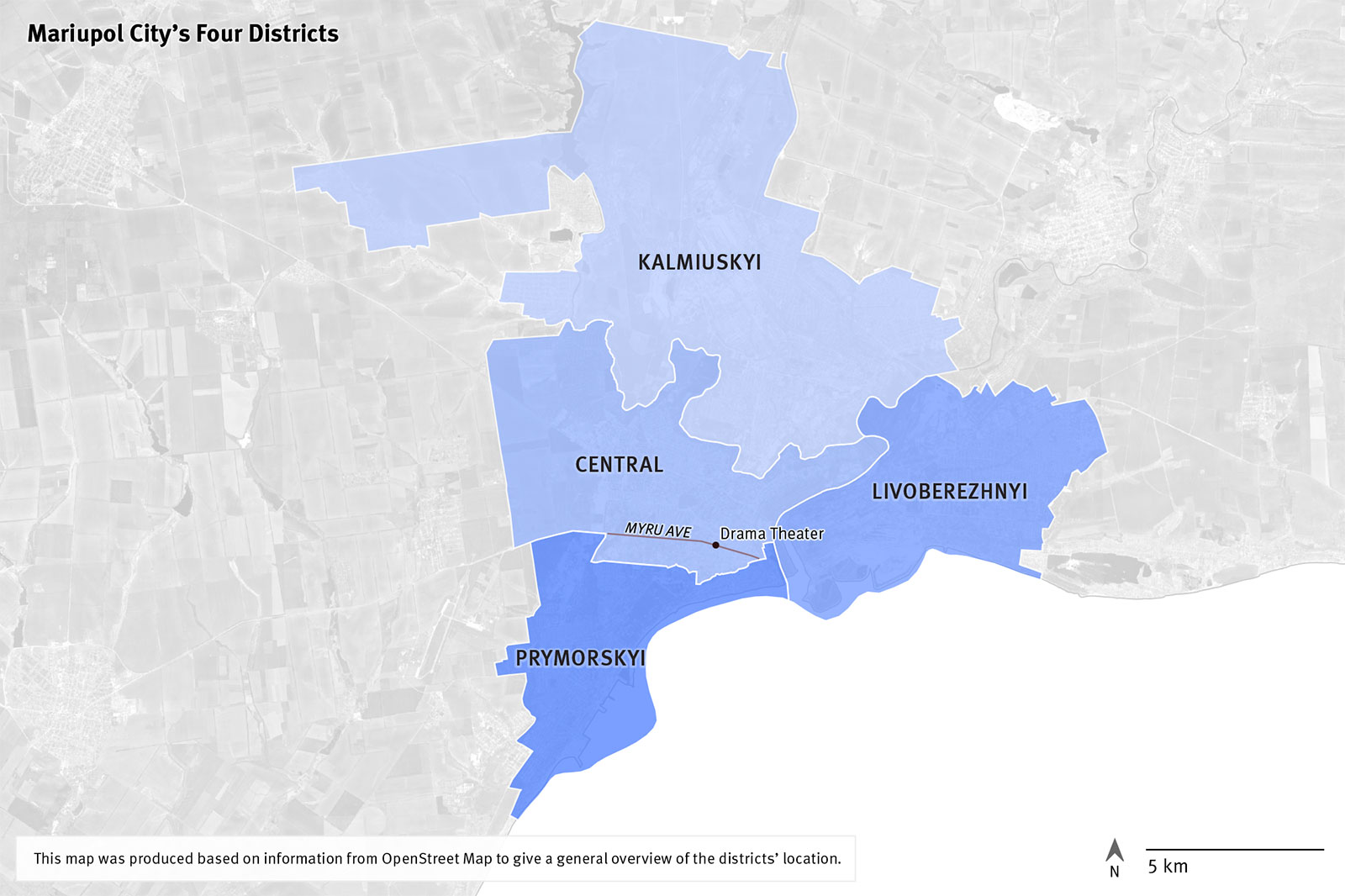

Mariupol is divided into four administrative districts: Tsentralnyi district, the Central District, often called “the City Centre” and home to the Donetsk Regional Academic Drama Theater; Kalmiuskyi District in the northeastern part of the city, often called “the factory area” as it includes the Ilyich Iron and Steel Works; Livoberezhnyi District, or the “Left Bank” in the easternmost part of the city, home to the Azovstal steel plant and separated from the rest of the city by the Kalmius River; and Prymorskyi District, or “the port,” in the southwestern part of the city.44

The following timeline of Russian forces’ attack and capture of Mariupol is based on interviews with dozens of witnesses; reports from the Institute for the Study of War (ISW), a US-based think tank; and reports from the Ukrainian, Russian, and US governments.

February 24, 2022: Russian and DNR forces based themselves in nearby villages some kilometers to the north, east, and west of Mariupol and began attacking the city with long-distance weapons, including tank shelling and heavy artillery, multi-barrel rocket launchers, missiles, and airstrikes. Attacks from outside of Mariupol were initially focused largely on the Left Bank (Livoberezhnyi District), but soon targeted all of the city and continued in some areas until the end of March.

March 2: Russian forces all but surrounded Mariupol, but took a few more days to occupy certain areas to the north, due in part to significant Ukrainian resistance in the town of Volnovakha, about 50 kilometers to the north of Mariupol.

March 3 or 4: First Russian attacks hit Mariupol’s Central District.

March 9: First Russian ground forces arrived in the Central District.

Around March 10: Russian forces reached Kuprina Street, at the western end of Mariupol’s Central District.

March 12: Ukrainian forces left the Regional Intensive Care Hospital in the Central District, and Russian and DNR forces took over the hospital. Ukrainian forces deployed in a shop called “Tysiacha dribnyts” (“the 1000 Little Things”) on Myru Avenue, and Russian forces moved into a post office close to the Drama Theater.

March 15: Russian and Ukrainian forces deployed about 300 meters apart near the junction of Myru Avenue and Osypenka Street.

March 15 to 22: At least five Russian naval ships in the Sea of Azov started shelling the city.

March 17 to 19: Russian forces took control of the Port City shopping center about three kilometers northwest of the theater, as well as nearby areas. By March 18, Russian forces had pushed out Ukrainian forces from an area near a part of Shevchenka Boulevard.

March 23: Ukrainian forces and DNR forces were deployed a few hundred meters apart near the junction of Mytropolytska Street and Levanevskoho Street.

March 25: DNR forces took over Hospital #3, from where they fought nearby Ukrainian forces between March 28 and April 3.

April 1: Russian forces had captured all of the Left Bank with the exception of the westernmost areas adjacent to the Azovstal steel plant.

April 3: DNR forces took control of Hospital #4, about 1.2 kilometers from the eastern perimeter of the Azovstal steel plant.

April 7: Russian officials said they had “practically cleared” all Ukrainian forces out of the city center.

April 10: Russian forces had captured all of the Central District including Myru Avenue and areas to the north of Myru Avenue, stretching from Kuprina Street in the west to the Kalmius River, about four kilometers to the east of Kuprina Street.

April 20: Russian forces captured all of Prymorskyi District, to the south of Myru Avenue.

April 21: Russia publicly claimed it fully controlled Mariupol, with the exception of the Azovstal steel plant.

May 7: About 500 women, children, and older people, were evacuated from the Azovstal steel plant.

May 16 to 20: 2,439 Azov Regiment fighters and members of the 36th Marine Brigade in the Azovstal steel plant surrendered, cementing Russia’s full control of the city.

Chapter III Civilians Denied Access to Critical Infrastructure

As Russia’s assault on Mariupol intensified, by March 2 the entire city had lost access to power, water, and sanitation services.45 While tens of thousands of people fled Mariupol during the first few days of the assault, at least 450,000 remained. With Russian forces now surrounding the city, civilians were trapped for up to seven weeks in appalling conditions: holed up in the basements of apartment buildings and other shelters without access to running water, electricity, gas, heating, telecommunications, or information about what was happening around them in the city or the broader conflict. The estimated 150,000 people remaining in Mariupol by May only gradually regained access to these services in the second half of 2022.

The fighting significantly damaged the city’s electricity infrastructure, which in turn disabled the city’s telecommunications network as well as water pumping stations, without which piped water could not flow. The lack of water knocked out the city’s heating system at a time of sub-freezing temperatures. By the afternoon of March 1, about half of the city’s electricity grid, including some of the Central District and all of the northeastern Kalmiuskyi District, was offline, most likely due to the significant damage done to power lines and electricity pylons. By midday on March 2, the entire city’s water supply was cut off when a key filtration station that pumped water from a reservoir to the city lost power. Later that day, Russian forces may have intentionally targeted part of one electricity transformer station, Azovska-220, that supplied substations in the Central and Kalmiuskyi Districts. This cut power to the few remaining areas there that still had electricity.

To help people cope, volunteers and city council workers brought food and diesel for generators to shelters and hospitals,46 and transported water to distribution points throughout the city, braving attacks that damaged some of their trucks. Residents were forced to come out of their shelters to wait in line at wells and water distribution trucks, or to cook meals on makeshift wood fires, exposing themselves to the onslaught of shelling and artillery fire. Others resorted to drinking, bathing, and cleaning with rainwater or melted snow.

People in need of medical care—those injured in the fighting or who fell sick due to the dirty water, the extreme cold, or lack of medicine for preexisting conditions—struggled to make it to hospitals, given the dangerous conditions throughout the city.

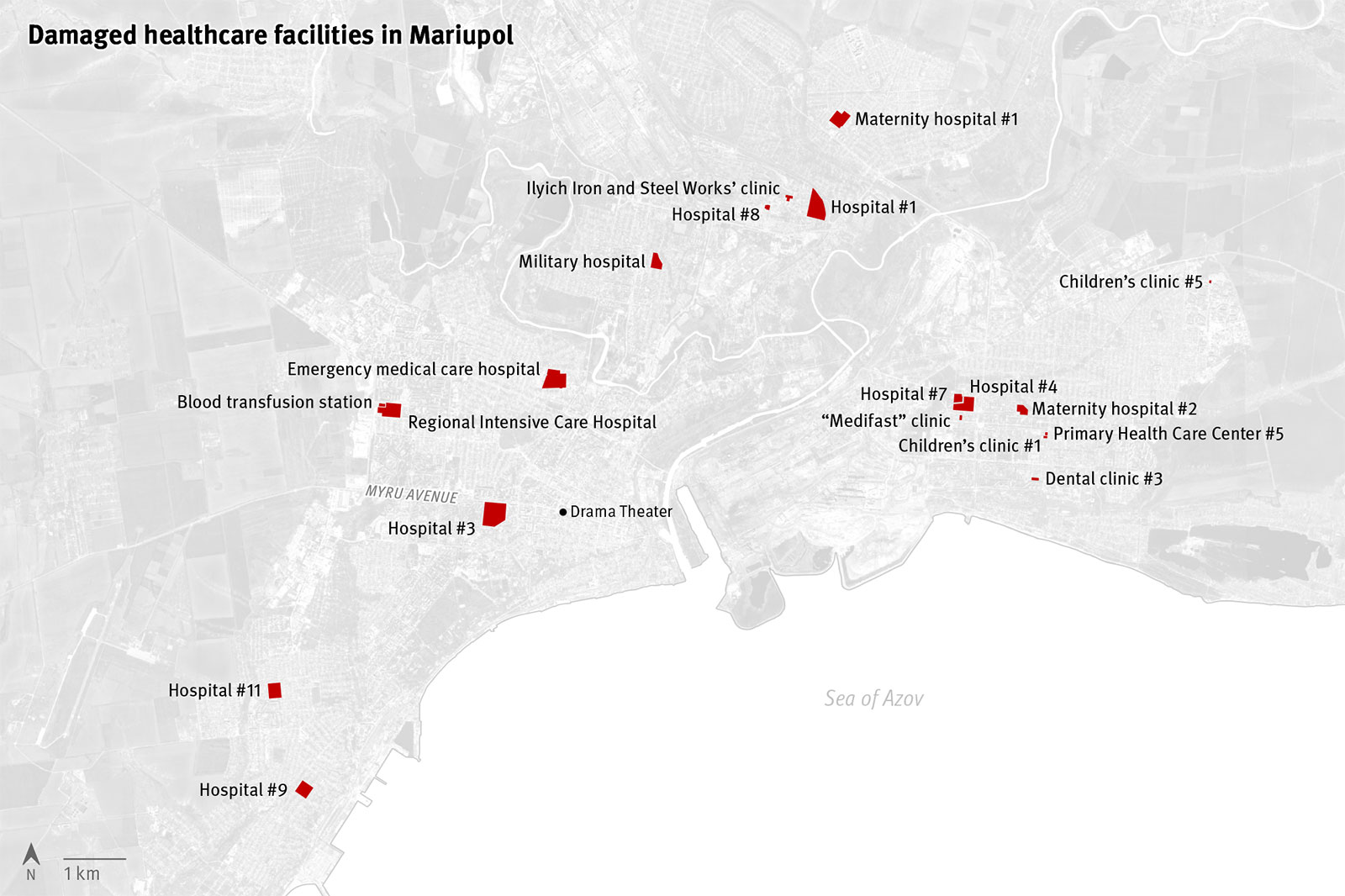

By the end of the fighting, all 19 of the city’s hospital campuses were damaged, which further inhibited their ability to provide care and likely contributed to the suffering and deaths not just during, but also after the battle for the city.47 At least five of the city’s fire stations were also damaged, likely obstructing the work of emergency responders.

Under international humanitarian law, electricity, water, telecommunications, health care, and emergency response infrastructure are considered “critical infrastructure” and among the “objects indispensable to the survival of the civilian population.”48 In at least one case – the attack on an electricity transformer station on March 2 – it appears that Russian forces deliberately targeted electricity infrastructure. In most cases, however, it remains unclear what caused the damage to the infrastructure.

As discussed above, electricity infrastructure is considered a dual-use object, an object that normally has both civilian and military purposes. Such an object is a legitimate military target if it is used in a way that makes an “effective contribution to military action” and its destruction in the circumstances ruling at the time offers “a definite military advantage.” Such attacks, however, must not have a disproportionate impact on the civilian population. Russian officials did not respond to questions about the intended targets of their attacks. Cutting electricity to the population as a whole would be disproportionate and in violation of international humanitarian law.

The following sections analyze the damage to Mariupol’s electricity, water, telecommunications, natural gas, healthcare, and emergency response infrastructure.

Electricity

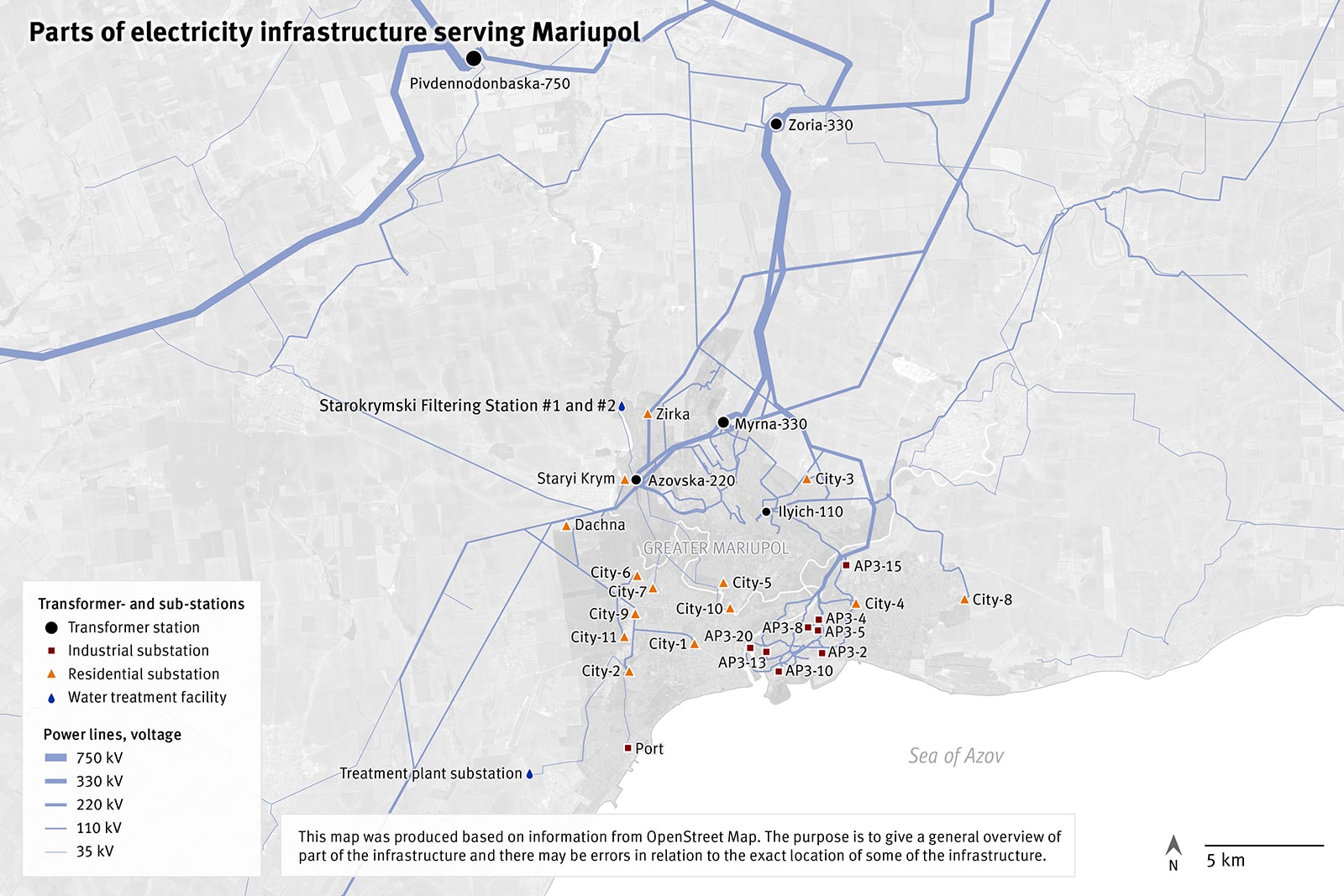

Mariupol depends on four electricity transformer stations.49 The main two, Zoria-330 and Myrna-330, supply two smaller stations, Azovska-220 and Ilyich-110. All four of them transfer electricity to dozens of large substations, which in turn supply medium-size substations that then feed electricity to the thousands of small substations attached to each residential and commercial building. Disabling Zoria-330 or Myrna-330 would have immediately disrupted the whole city’s electricity supply. However, we found no evidence on satellite imagery of damage to either of them, or to Ilyich-110, before March 2, when the entire city was cut off from electricity. Satellite imagery shows the main building at Myrna-330 was damaged between March 14 and 19, but does not show any damage to the electricity infrastructure at the station. Satellite imagery from March 23 shows black marks on the ground near Ilyich-110 that are not present on imagery taken the day before. Imagery from April 4 shows no damage to the transformer stations’ main building, but the next available image, on April 9, shows damage to the rooftop.

Ukraine’s largest private electricity company, DTEK, ran most of the city’s electricity infrastructure.50 The company shared with Human Rights Watch a power line register in which its staff recorded when various parts of the network failed between February 24 and March 2, including any known reasons for the failures.

Between February 25 and March 2, DTEK recorded eight incidents in which 23 of the city’s dozens of electricity substations, including the one powering the Azovstal steel plant, went offline in groups of two or more.51 Simultaneous substation failure suggests that they did not go offline as a result of damage to the substations, but instead because of damage to power lines or electricity pylons, which relay electricity from the transformer stations to groups of substations. During a ninth recorded incident, a single electricity substation in the compound of Starokrymski Filtering Stations #1 and #2, that pumps canal or reservoir water into pipes that run to the city, went down at about midday on March 2, probably due to the downing of the power line that connects it to the Azovska-220 transformer station.52

In two cases, DTEK recorded incidents in which areas dependent on two or more substations lost electricity. The first happened on February 25, when Left Bank residential areas dependent on two substations53 lost electricity at the same time. On February 26, the Mariupol City Council said that 188 “substations”-likely referring to smaller substations at the residential property level-had been damaged,54 leaving 41,229 households55 without power.

The second happened when residential areas in the Central and Prymorskyi Districts dependent on seven substations56 all went offline at the same time for some hours on February 28 and again on March 2. According to DTEK,57 this was because damaged nearby powerlines needed to be repaired. They were “reconfigured by cutting off damaged sections and installing additional switchgear” on February 28 or early on March 1, and were damaged again on March 2.58 Satellite imagery from March 9 shows two damaged electricity pylons located between the Azovska-220 transformer station and the seven substations.

We also analyzed other satellite images taken between March and April 2022 that show damage to a number of power lines and electricity pylons in various parts of the city and its outskirts. Two residents said that at some point in March, attacks by Russian forces hit electricity pylons near the city’s California market59 and about 700 meters south of the western end of Myru Avenue.60 Satellite imagery from between March 9 and May 12 shows damage to 11 of the city’s substations, which appears to have occurred after March 2, by which time the entire city was already cut off from electricity. We were unable to determine whether the substations and lines were intentionally damaged by Russian or Ukrainian forces during the fighting.

For the above reasons, and because residents living in many different parts of the city said they continued to receive electricity until March 2, the damage to the city’s substations appears to have occurred after March 2, by which time the entire city was already cut off from electricity.

According to DTEK, at 3:30 p.m. on March 2, one of the transformers at the Azovksa-220 station was damaged by reported shelling. This cut electricity to the last three dependent substations supplying electricity to residential areas in the Central and Kalmiuskyi Districts. The station is located about 8 kilometers north of the center of the city and far from any other buildings. Satellite imagery from March 12 shows damage to one of the station’s transformers, as well as damage to what appears to be a communications tower 90 meters away. There is no other damage to the facility, suggesting a targeted attack on the transformer.

Water

The lack of electricity had a knock-on effect for civilians’ access to water.61 Damage to the electricity network on February 25 stopped the pumps that sent canal-delivered river water to the city’s pipes, forcing the city to rely instead on reservoir water.62 An attack on electricity infrastructure on March 2 downed the pumps that transferred the reservoir water, leaving the entire city’s population without access to running water.63 Volunteers tried to help residents cope with the loss of running water by collecting water from wells and springs and trucking them to distribution points across the city. But this came at great risk, as volunteers and residents had to brave the ongoing shelling while they moved across the city to distribute or collect water and wait in line for hours at distribution points.

How the Taps Went Dry

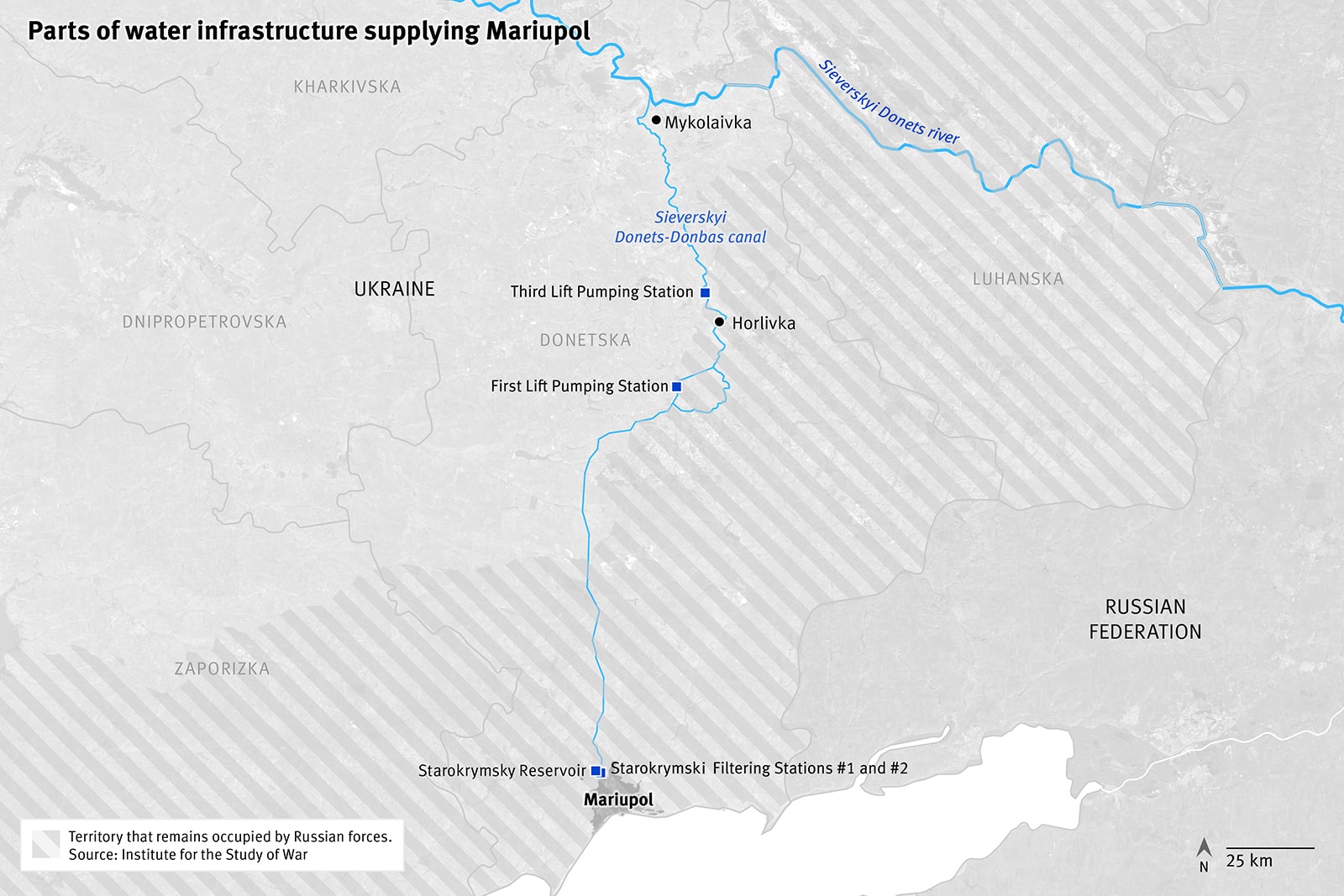

The Siverskyi Donets River is Mariupol’s main water source. In Mykolaivska, 200 kilometers north of Mariupol, the water flows into a canal that takes the water 50 kilometers, mostly above ground, to the town of Horlivka, 130 kilometers north of Mariupol. There, the Third Lift Pumping Station of the Siverskyi Donets-Donbas Canal pumps water from the canal into at least three sets of pipes.64 This pumping station is one of the most important pieces of infrastructure in the Donbas region and is strategically important to both Ukraine and Russia, supplying water to three million people in the region.65

The water pipes that begin in Horlivka run above ground for some kilometers and then underground to reach the First Lift Pumping Station66 located six kilometers from Vasiylivka village, about 120 kilometers north of Mariupol. The pipes continue underground from Vasiylivka until they reach Starokrymski Filter Stations #1 and #2, located in a compound about 10 kilometers north of Mariupol city center and just to the south of the Starokrymsky Reservoir.67 The filter station pumps and filters water from the underground pipes-and, if needed as a back-up water source, from the Starokrymsky Reservoir-into mostly underground pipes that run to Mariupol, according to the Head of Mariupolvodokanal, one of the two companies supplying the city with water.68

On February 19, part of the Vasilyvika pumping station was damaged by an explosion that was captured on camera.69 We were unable to determine the cause of the explosion.

The head of the Donetska Regional Civil-Military Administration said that on the same day, Starokrymski Filter Stations #1 and #2, about 100 kilometers to the south, switched from pumping canal water to pumping reservoir water to Mariupol, implying that the February 19 incident stopped canal water from reaching the Filter Station.70 A UN committee dealing with water and sanitation issues said that after the incident, 90,000 people in the Volnovakha area had switched to reservoir water and that “cities like Mariupol are similarly shifting to water from reservoirs.”71 This implies that canal water no longer flowed from Vasilyvika to Mariupol or that it was flowing at a reduced rate. However, the director of Mariupolvodokanal, and the deputy administrator of Mariupol City Council, said water continued to flow from the canal to Starokrymski Filter Stations #1 and #2 until February 26, the day on which the stations had to switch to pumping reservoir water because of the complete loss of canal water the day before.72

The loss of canal water on February 25 can be explained by what the UN committee said involved the “de-energiz[ing]” – a term that refers to a loss of power supply – that day of the strategically crucial Third Lift Pumping Station.73 This meant an end to water pumping from the Siverskyi Donets River into the Siverskyi Donets-Donbas Canal. Three million people, including all residents of the Donbas region-people in areas under the control of DNR forces, as well as Mariupol-lost access to canal water that day.74

According to the DTEK register, on March 2, at 12:15 p.m., Starokrymski Filter Stations #1 and #2 stopped functioning because the electricity substation supplying the Filter Stations was “disconnected,” probably because the power line connecting it to the Azovska-220 transformer station was downed. The UN committee said that on March 2, the Voda Dobasa water company informed it that shelling at about 1 p.m. had damaged “a number of power lines” and that this meant that all water pumping stations in Mariupol, including Starokrymski Filter Stations #1 and #2, had stopped functioning.75 Satellite imagery of the filtering stations from March 9 shows damage to the station’s roof and some ground nearby, but not to the compound’s electricity substation.

The director of Mariupolvodokanal said his company’s 1,000 or so staff continued to work until March 2, when the loss of electricity citywide cut power to all the water pumps.76 He also said that 40 percent of the city’s “small pumping stations that supplied water to the upper floors of buildings” were damaged in the fighting after March 2. In May 2022, Mariupol’s mayor, Vadym Boychenko, said that “all 22 [of the city’s] pumping stations had been destroyed or flooded” and that “more than 50 percent of the water supply network was damaged.”77

Collecting and Distributing Water at Great Risk to Volunteers and Residents

“On April 2, my husband went to collect water at a well nearby, but he never returned. A neighbor later told me there had been shelling at a crossroads when he would have been passing through. I looked for him for five days. I never saw him again.”

— Woman from Kalmiuskyi District who survived three months in Mariupol before fleeing the city.78

After the taps went dry on March 2, about 100 Mariupolvodokanal staff and other volunteers started to collect water at informal water sources such as springs and wells, and truck them to distribution points at hospitals and larger shelters, including schools, kindergartens, and basements, according to the director of Mariupolvodokanal.79 After running water stopped, he said, the city’s main source of water became a well about one kilometer to the east of the Drama Theater, where his staff used diesel-powered pumps to extract water. “That well saved many lives,” he said.80 Other water sources included the Kalchyk River,81 a canal close to Mariupolvodokanal’s headquarters, and a fire hydrant near the Drama Theater.82

Mariupolvodokanal staff and volunteers distributed water using eight water tankers, each with a capacity of about 10 cubic meters, as well as two smaller trucks, which allowed them to deliver between 80 and 100 cubic meters of water a day throughout the city in the first few days after March 2.83 Water delivery points included the Drama Theater, the Terra Sport Gym,84 the Savona Cinema next door,85 a location close to Mariupovodokanal’s headquarters, and the city’s central market, called “Tsentralnyi.”86 City officials also tried to inform residents about where to find springs and wells, including in City Garden, the mosque at Nakhimova Avenue 41, the Chaika Café on the Left Bank, and a place near the Open llichyvets Stadium.87

These efforts provided desperately needed water to residents across the city. However, the volunteers organizing the distribution, the water tanks themselves, and the residents braving the city streets to reach the wells or distribution points to then queue up for up to six hours, were exposed to barrages of shelling, rockets, and air-dropped munitions.88

The intensity of the fighting meant the water trucks could not reach the Left Bank after March 10, although Ukrainian police took one of the tankers after that date to deliver water to Hospital #4. Other areas that were impossible to reach at various points in March included the city’s 17th and 23rd Sub-Districts and the whole of Kalmiuskyi District.

Mariupolvodokanal’s headquarters was attacked the night of March 15-16 and again the night of March 16-17.89 Mariupol’s first deputy mayor said that a girl about 10 was injured in a nearby building during one of the attacks.90

An attack in early March near the Shans supermarket at Latysheva Street 23, where city council volunteers distributed water and humanitarian aid, killed three or four people, according to a staffer of the Donetsk Regional Bureau of Forensic Medicine, who saw the bodies.91

By March 18, shelling and other attacks had reportedly damaged or destroyed all but two of the eight water tankers.92 One of the tankers was destroyed on Metalurhiv Avenue, another on Bakhchyvandzhi Street that runs south of, and parallel to, Myru Avenue, and a third was destroyed near the Philharmonic Hall next to the Drama Theater.93

One man described an attack on March 15, at around 8 a.m. when he went to collect ground water from a garage compound about 500 meters south of the Azovstal steel plant in the Left Bank. “There were about 30 of us when the attack happened and it killed 20 people and wounded many others, including two people who had come with me from the building where we were sheltering,” he said. “The Ukrainian forces arrived quickly and took the injured to the hospital.”94

Later that day or the next, the man said he saw the bodies of about 10 people in civilian clothes near another ground water source, which he said was next to a building belonging to an industrial bread manufacturer called Khlibokombinat and an administrative building belonging to a military recruitment center. The man said he did not know how the people died.

A military nurse said she had heard from others that there were “many corpses” near a well in Peremohy Park.95 She had also heard that some of the injured people she saw in a shelter under Hospital #3 between March 17 and April 25 had been injured while collecting water there.

A man described the scene at the well near the Chaika Café on the Left Bank in mid-March:

I saw three corpses near the well. One of them was a girl wearing high boots with fur on the outside. One was a man with a bullet wound in his neck. All three had also been shot in their chests and were wearing civilian winter clothes. Some other people and I moved them behind a nearby building and the owner gave us blankets to cover them. The owner didn’t know what had happened but as far as I understood, there had been some fighting in the area the evening before.96

Another man said that on the morning of March 10, he left his house at Metalurhiv Avenue 117 to collect water from a nearby river, when shelling started:

We didn’t even make it 15 meters from our entrance. I was immediately injured on the right-hand side of my body and my wife’s brother was very badly injured in his back. I took him to Military Hospital #555, and he died during the operation. He was 52.97

A deputy head of Mariupol City Council said that a doctor called Andrii Ivanovyh Hnatiuk was shot dead on March 27 by Russian forces as he walked from Hospital #4 to fetch water at a well to the northwest of the hospital near the local cemetery.98 A health official said that at some point in March she had heard that a doctor working at the city’s Regional Intensive Care Hospital99 was killed while on his way to fetch water for the hospital from a nearby well, though she didn’t know how or by whom.100

A woman said that she had heard that “a lot of [her] neighbors were killed near a water spring near School #31.”101 A man said he had heard that at some point between March 9 and 11 during the early morning, an attack killed three people near a water source on Persha Slobidka Street.102

Another man was killed by a shell fragment as he walked towards a water collection point at the nearby mosque in mid-March.103

A doctor said he heard that at some point after March 8, a woman who was sheltering in a building near his, close to the Savona cinema, was killed during an attack while she was fetching water.104 A man said that on March 12 at about 10 a.m., he saw the body of a man who he had been told had been killed by mortar fire as he walked from 44 Fontanna Street towards the Kalmius River to get water.105

A woman said one of her neighbors went to collect water and returned with a back injury from an attack.106 And a man said he knew of a number of people who left his building, at Morskyi Boulevard 54, and the neighboring building, at number 56, to fetch water who never returned, though he did not know why.107

Natural Gas and Heating

“At nights I cried from the cold.”

— Mariupol resident, who endured three weeks in sub-freezing temperatures.108

Residents of Mariupol rely on natural gas to cook food and to fuel boilers that heat water, including for heating systems.109 By March 6, the natural gas supply was cut off throughout the city because of damage to a major pipeline that supplied gas to the city and half of the Donetsk region.110 But heating systems had already stopped working on March 2: with no electricity to pump water, no water reached the natural gas-fueled boilers. Many residents described how they suffered from the cold during those initial weeks of sub-freezing temperatures. And when their stoves no longer worked, they had to go outside to heat water or prepare warm meals on makeshift fires, exposing themselves to both the cold and the shelling.

In addition to the major pipeline damage on March 6, the fighting damaged 32 of the city’s buildings housing natural gas boilers that transferred heated water through pipelines to about 1,900 residential buildings, as well as to public buildings and companies.111 He also said that the fighting caused damage to about 360 kilometers of the city’s 600 kilometers of pipelines for heated water, including to some of the 5 percent of the pipes that run overland and much of the remaining underground pipelines that were damaged after water froze inside them, causing them to rupture. He said his department estimated the repair cost would amount to 5 billion hryvnia (UAH), or about US$135 million.

Telecommunications

“I remember how we came to a tower and saw Ukrainian soldiers standing nearby with yellow ribbons on their shoulders. We asked them what was going on because we had no internet access, and we were cut off from the rest of the world. We did not understand whether Mariupol was under Ukrainian control or not. We didn’t even know whether our president was in Ukraine.”

— Mariupol resident who went in early March to an old water tower near the Drama Theater after a week without phone network access112

During the first few days of Russia’s assault on Mariupol, residents lost nearly all access to mobile phone networks and the internet, shutting them off from the world and preventing them from communicating with loved ones or accessing news about the conflict, possible evacuation routes, or humanitarian aid distribution points. Throughout the siege, this inability to communicate compounded residents’ daily fears and struggles as they worried about the fate of their relatives, friends, and colleagues. They used word of mouth at water and aid distribution points to try to pass messages on to friends and loved ones in other neighborhoods, to let them know they were still alive and where they were sheltering-or in some cases, to indicate who had died and where they had been buried in makeshift graves. Residents also risked walking the city streets, and exposing themselves to artillery fire, as they searched for one of the few locations in the city where they could still occasionally pick up a signal on their phones.

Mariupol’s city council first posted a message relating to the cutting of phone coverage on February 28.113 Before February 24, Mariupol had three telecommunication providers: Kyivstar, LifeCell, and Vodafone. LifeCell reported that its services in Mariupol were “disconnected” as of February 27 after its “transmission sites” were destroyed and “optical cables in the main and backup routes” were damaged.114

Kyivstar told Human Rights Watch that the lack of electricity citywide by early March made mobile phone coverage impossible, except at two locations: the immediate vicinity of the Drama Theater, from where Vodafone continued to transmit a signal until “its services were destroyed soon after by shelling,” and an area close to Kyivstar’s seven-story headquarters.115

Some residents said they found weak phone signals in certain locations in early and mid-March, including at the Regional Intensive Care Hospital,116 near the Savona cinema,117 and near the Kyivstar building, which allowed them to call or send messages to their relatives.118

Kyivstar’s office contained a core base station, the central hive of mobile telecommunications that was connected to 148 base stations, which in turn transmitted wireless signals throughout the city.119 Kyivstar’s chief technology officer reported that “one by one all these base stations went down [initially in early March] because of the power connection [and] then because of physical damage.”120

Kyivstar told Human Rights Watch that residents could continue to connect to Kyivstar’s signal near its office after March 1 because the company’s engineers placed a diesel-powered transmitter and antenna next to a fourth-floor window.121 A shortage of diesel after March 15 meant they only switched it on for a few hours a day. One of the city’s deputy mayors confirmed that the city council provided the diesel generators.122 The company said a March 15 attack damaged the building’s fifth and sixth floors. The building was then significantly damaged by shelling on March 20, and Russian forces were briefly in the building later that day, according to Kyivstar.123 Satellite imagery from March 29, 2022, shows damage to the fourth, fifth and sixth floors on the southern side of the building. Photos taken on March 19 by employees of Kyivstar inside the building show damage to rooms whose windows are on the southern side of the building, while a video posted on February 8, 2023, on social media shows the damaged façade.124 On March 21, all staff and their families who had been sheltering in the building left, except for two engineers who left on March 24.125

Hospitals

Human Rights Watch identified 19 hospital campuses citywide and found that all of them were damaged during the fighting. The campuses of Hospital #1 and Hospital #4 were among the most heavily damaged, with some buildings destroyed.126 To varying degrees, the physical damage and destruction limited the ability of hospitals to provide life-saving care, compounding the challenges hospitals faced due to limited supplies and medicine, the lack of electricity, and limited fuel to power their generators. For additional information on damage to hospitals, see Damage to Healthcare Facilities in Chapter VI.

Fire Stations

At least five fire stations in Mariupol were damaged in March and April-fire stations 22, 23, 24, 25 and 53, likely limiting their ability to respond to major attacks and put out fires throughout the city.127 Human Rights Watch analyzed satellite imagery that showed that station 22 was damaged between March 9 and 12, with significant damage on the roof; station 23 was damaged between March 14 and 19; station 24 was completely destroyed between March 14 and 19; station 25 was completely destroyed between March 30 and April 3; and station 53 was damaged between April 11 and 15.128

An emergency responder who led the fire response in the city between February 24 and March 14 said he was based at Fire Station #22, which was struck on March 10 at a time when 287 people were sheltering in the basement, including first responders and their families. He said that the attack killed one person and injured nine. He also said that his team prioritized putting out fires in residential buildings, not commercial buildings such as shopping centers and offices, and that his teams got their water from reservoirs around the city where he said there was always enough water.129

Truth Hounds spoke with a man who moved with his family to a building that was part of Fire Station #22 and who described the moment the building was struck:

It was between 9 and 10 a.m. on March 10. I was on the third floor with my family when I heard an explosion. It hit the second floor and we ended up on the second floor, under the rubble. My wife and I were rescued after 30 minutes and my son after three hours. Both of them had bad injuries to their arms and legs. Most of the people living there at the time were in the basement and were not hurt. Others who were on the upper floors had minor injuries. A friend and colleague of mine, Pankov Oleksiy Serhiyovych, was killed but they didn’t find his body until months later.130

Services in Mariupol Since May 2022

After taking over the city in April 2022, Russian forces took many months to even partially restore the remaining residents’ access to electricity, water, and basic healthcare services.

According to one city official, as of September 2022, city residents still had limited access to food, water, health care, and other social services.131 In some medical centers, she said, medical care was limited to measuring blood pressure and auscultation, or listening to lungs, the heart, and the abdomen. One of the city’s deputy mayors said that, as of the end of August 2022, attempts to fix part of the electricity grid had resulted in fires and that as of mid-summer, some districts had been sporadically getting electricity, but that none had access to natural gas.132

In early May 2022, the Emergency Situations Ministry of the DPR said that its filtration plant had been relaunched for the first time since a power substation was damaged on March 2 and that, as a result, water supply would be restored in Mariupol on May 12 or 13.133 Yet it was only in early August that some districts started to receive running water for a few hours at a time.134 Even with running water partially restored, city officials raised concerns about the continued risk of water-borne infectious diseases, including cholera, since the sewage treatment and drainage systems had not been restored.135 Mariupol was also still relying on local informal water sources, such as small rivers and water holes that were known from past testing to contain cholera-causing bacteria, as it was still not receiving water from the Donbas canal, which had been damaged in late February.136

On October 9, the DNR’s Ministry of Construction said that water had been restored to all four of the city’s districts.137 The director of Mariupolvodokanal, who fled the city but continued to monitor the water situation in Mariupol after it was occupied, told Human Rights Watch in December 2022 that, according to his assessment, 80 percent of the water supply infrastructure and 50 percent of sewage treatment infrastructure had been restored.138 In March 2023, he said he thought that almost all damaged water infrastructure had been repaired, but that the assault on the city had completely destroyed four sewage treatment plants, including two on the Left Bank, on Azovstalska Street and in Skhidnyi District, and two on the western side of the city: Pumping Station #6 near Zelinskoho Street and one on Mytropolytska Street.139 He said that his company estimated that the cost of repairing damage to the city’s water infrastructure would amount to about US$700 million.140

By February 2023, the occupying forces had largely repaired the electricity and natural gas grids, in addition to the water infrastructure, but there were still regular cuts.141 These cuts were ongoing in December 2023.142

Chapter IV Struggling to Survive in Shelters

Between February 24 and mid-April 2022, tens of thousands of Mariupol residents took shelter for days or weeks wherever they could, to reduce their risk of death or injury from airstrikes, shelling, and other attacks. Some fled to collective shelters in hospitals and in other non-residential buildings, some of which were supported by city officials and volunteers. Others stayed in the basements of their own buildings or fled to other basements.

With no way to bring food into the city or keep shops open, people survived on food they had in their apartments, what volunteers distributed, or food that people risked their lives to find and bring back to the shelters to share with others. Without running water, people tapped radiators, collected rainwater, melted snow, and dodged shelling to fetch water from springs and wells. Without heating and electricity in below freezing temperatures, they huddled together under blankets. With the threat of unpredictable attacks, they risked their lives to cook meals on makeshift wood fires in courtyards and near building entrances, trying to increase their chances of making a swift retreat to basements in case of sudden attack.

The outside world adopted the basements as symbols of Mariupol’s resistance.143 Inside them, civilians survived in the harshest of conditions: terrified, cold, wet, thirsty, and hungry in the darkness. Unknown numbers of people died underground, stricken down by the elements and with no access to drugs and medical treatment.

Shelters Across the City

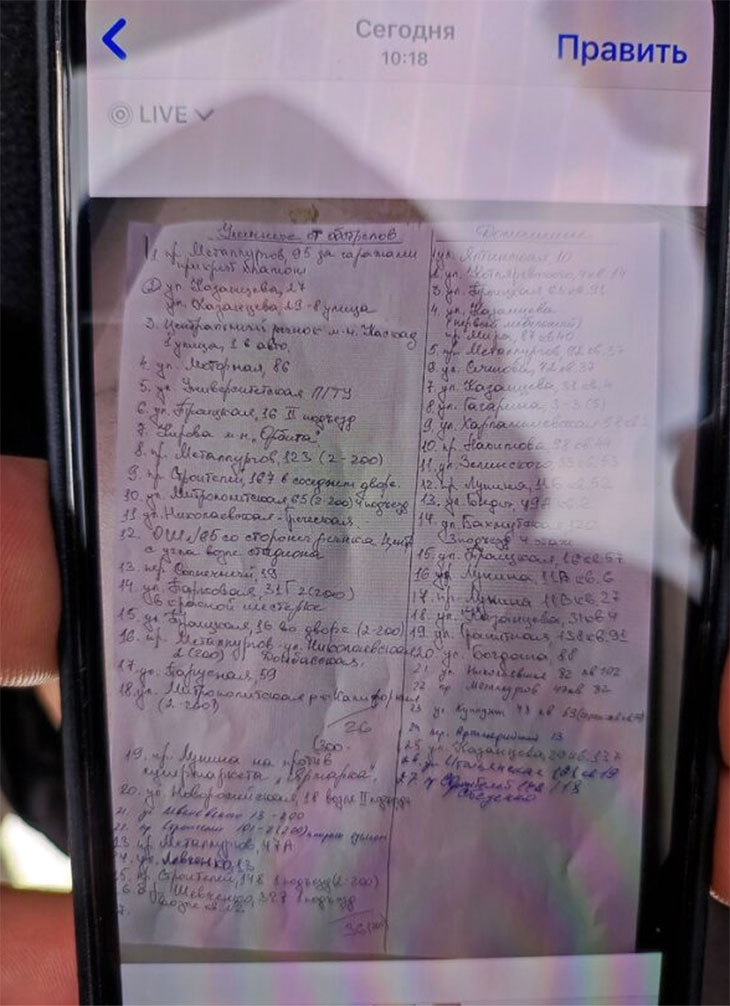

On February 24, the Mariupol City Council published a list of 1,033 addresses entitled “List of basement and other underground premises, in which, if necessary, it would be possible to shelter the population of Mariupol.”144 Almost all were in residential buildings. Many residents stayed in these designated shelters, while thousands of others sheltered above and below ground in dozens of mostly non-residential buildings.

City officials and volunteers mobilized to support residents during the initial days of the Russian assault, including by providing transport to help people relocate from the Left Bank and villages near the outskirts of the city to shelters and neighborhoods in the city center that were considered relatively safer in the early days of the assault. Volunteers baked thousands of loaves of bread until electricity was cut on March 2, and they collected food from markets to bring to the shelters. They also organized the collection and distribution of water, blankets, clothes, diapers, batteries, and medicine, as well as diesel to power generators at hospitals, coordinating these efforts via radio communication and word of mouth.145

These efforts provided life-saving assistance to thousands of residents, but delivering aid in many parts of the city became increasingly difficult as the Russian attacks intensified. Officials and volunteers faced mounting challenges to communicate, coordinate, and move around the city. By March 5, such efforts had become very dangerous and shelters across much of the city were soon no longer accessible.146 In some cases, though, hundreds of people remained in the same shelter for weeks, supported by volunteers.147

Based on interviews with city officials, volunteers, and residents, as well as posts on the Mariupol City Council’s Telegram channel, we identified 27 locations, including two residential buildings, that functioned as shelters that were supported by city officials and volunteers in late February and March.148

Shelters Supported by City Officials and Volunteers

Central District

Myru Avenue and Nearby

- Donetsk Academic Regional Drama Theater, Teatralna Square 1

- “Molodizhnyi” Palace of Culture, Kharlampiivska Street 17/25

- Social Services Center of the Central District, 80 Myru Avenue

- Residential building at Kazantseva Street 19a

- A number of University buildings belonging to the Pryazovskyi State Technical University including Myru Ave 68 and University building #2 at Kazantseva Street 3

- TSUM Department Store, Myru Avenue 69

North of Myru Avenue

- School # 27, Troitska Street 56

- Savona Cinema, Budivelnykiv Avenue 134

- Terra Sport Gym, Budivelnykiv Avenue 132

South of Myru Avenue

- Mariupol Chamber Philharmonic, Metalurhiv Avenue 52

- Sports Volleyball Complex, also known as “The Cupola”, Metalurhiv Avenue 52

- Palace of Aesthetic Education, also known as “The Palace of Pioneers,” Metalurhiv Avenue 19

Prymorskyi District (southern part of city)

- Budivelnykiv Avenue 56

- Mariupol Maritime Lyceum, Budivelnykiv Avenue 28

- Regional Children’s Tuberculosis Sanitorium, Prymorskyi Boulevard 23

- School #26, Chornomorska Street 12

- Building formerly housing the Komsomolets Cinema, Nakhimova Avenue 172

- Preventive Medicine Sanatorium “Chaika”, Nakhimova Avenue 39

Livoberezhnyi District (Left Bank)

- Youth Art Building at Azovstalska Street 32

- Left Bank Culture Center on Azovstalska Street

- Social Services Center of the Left Bank, Meotydy Boulevard 20a

- “Social Dormitory” on Kyivskyi Lane 10