Protecting the endangered Asiatic cheetah. Tweeting a satirical poem. Attending a climate conference. Campaigning against a power plant. These actions hardly conjure images of suicide bombers or coup plotters. Yet, they have been labelled “eco-terrorism,” “extremism,” or “threats to national security” by governments and businesses that seek to block the work of environmental activists.

As young people around the world gather for a global climate strike on Friday, and as the 25th Conference of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP25) begins in Madrid on Monday, conference delegates would do well to consider that one important way to protect the environment is to protect environmental defenders.

To be sure, environmentalists face dangers beyond being labelled security threats. From the Amazon rainforest to South African mining communities, activists defending ecosystems and ancestral lands are threatened, attacked and even killed with near-total impunity. But the unjust labelling of environmentalists as dangerous criminals or threats to national security is often more insidious, as it is generally carried out under the aegis of the law.

Authorities have an obligation to prosecute criminal acts. But typically, environmental defenders peacefully exercise their rights to freedom of speech, association, and assembly. Only in exceptional cases would their acts meet a generally-accepted definition of terrorism. And when environmentalists engage in civil disobedience, they do not usually aim to undermine the rule of law. Yet, we should consider the following:

- In Poland, days before hosting the COP24 in December 2018, authorities issued a terrorism alert and denied entry to at least 13 foreign climate activists registered to attend, calling them security threats. Poland also empowered the police to collect data about conference participants without judicial oversight or participants’ knowledge.

- In France, days before hosting the COP21 in November 2015, authorities placed at least 24 climate activists under house arrest using emergency counterterrorism measures enacted after the deadly Paris attacks that month. The activists were accused of flouting a ban on COP21 protests.

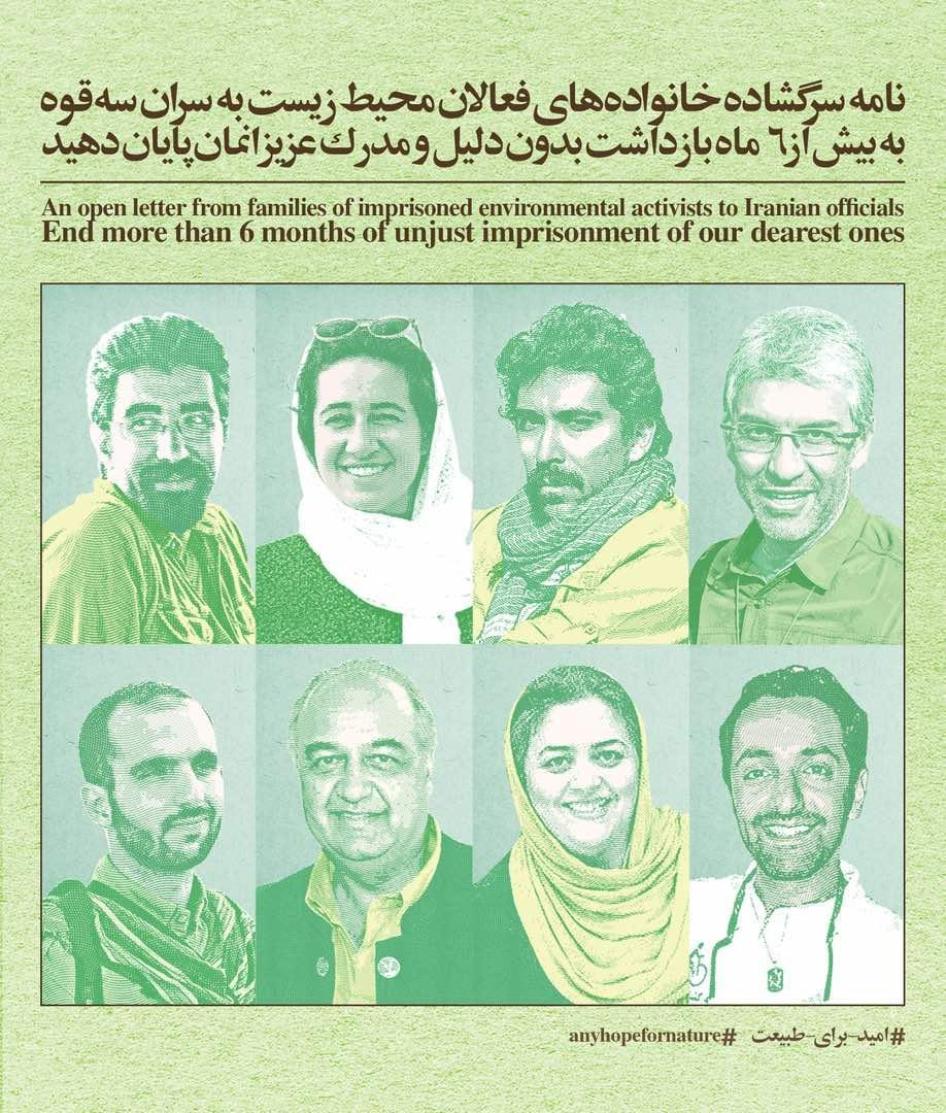

- In Iran, eight members of the Persian Wildlife Heritage Foundation, imprisoned since early 2018, were just handed prison terms of up to 10 years for allegedly spying for the US. During a flawed trial, the Islamic Revolutionary Guards accused them of using their work protecting the endangered Asiatic cheetah as a cover. The group’s founder, also arrested in 2018, died in custody under suspicious circumstances.

- In Kenya, authorities have unjustly accused environmental activists opposing a mega-infrastructure project of ties to the extremist armed group al-Shabab and threatened, beat, and arbitrarily detained them. In July, a court suspended the project’s coal-fired power plant. Activists contend the development will still destroy forests, kill fish, and displace communities.

- In the Philippines, President Rodrigo Duterte in 2018 placed 600 civil society activists, including environmentalists, on a list of alleged members of the country’s communist party and its armed wing, which he declared to be a terrorist organisation. Until a court intervened, the list included Victoria Tauli-Corpuz, an indigenous Filipina who is the UN special rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples and has protested Philippines mining projects.

- In Ecuador, eight years passed before environmental activist José “Pepe” Acacho was cleared of “terrorism” charges for opposing mining and oil exploration in the Amazon.

- In the US in 2018, the then-interior secretary blamed wildfires on “environmental terrorist groups” that opposed logging. In 2017, a pipeline operator sued Greenpeace and other environmental groups for a “rogue eco-terrorist” campaign against an oil pipeline. A court dismissed the lawsuit in February. Largely peaceful protesters said the underground pipeline threatened Native American sacred sites and drinking water.

- In Russia, since 2012, at least 14 environmental organisations have had their work curtailed and in June, the head of the group Ecodefence!, fled the country to avoid being targeted under an abusive “foreign agents” law. In April, a court fined an environmental activist for “mass distribution of extremist materials” for posting a satirical poem about mining oligarchs.

During the COP25, participating governments should encourage activists to air their concerns about the climate crisis and their own safety, and draw on their combined expertise to help identify solutions.

They should also commit to rigorously implementing treaties that protect environmental defenders. One is the Aarhus Convention, which the European Union and Poland have been criticised for flouting. Another is Latin America’s Escazu Agreement, which requires just five additional ratifications to enter into force. Chile, which will preside over the COP25, should lead by example and ratify it.

COP25 delegates should recognize that to genuinely protect the environment, they also need to protect its defenders—including those unjustly targeted in the name of security.

Also check out this web essay by Letta ,Cara, and Katharina Rall.