In May, the Ugandan Parliament passed one of the most extreme pieces of anti-LGBT legislation in the world. Existing criminal law already provided for life imprisonment for gay sex. Now, repeat offenders could face the death penalty, activists face up to 20 years in prison, and all information on lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) issues could be censored.

Like other former colonies, Uganda inherited its criminal code from Britain, a legacy of empire that continues to have far reaching consequences in Uganda and in the other 66 countries that still criminalize same-sex conduct. But instead of rejecting this relic of colonial rule, Uganda has accentuated its anti-gay rhetoric and extended the reach of its anti-LGBT laws. Many Ugandans are fleeing to safer destinations, such as South Africa, where the constitution explicitly protects people from discrimination based on sexual orientation.

This stark contrast between two African countries – one that protects, and another that persecutes - is a microcosm of a world in which the rights of LGBT people remain highly contested.

In June 1969, patrons at The Stonewall Inn, a New York City gay bar, fought back against police officers conducting a routine raid, precipitating a three-day riot. While Stonewall was not the first act of open defiance - activists in Europe and parts of Latin America had fought for years to improve the legal situation and social standing of LGBT people - Stonewall has become an international marker of resistance and a milestone of progress.

Remarkable advances have been made. Since 1969, 78 countries have decriminalized same-sex relations. Just last year, three Caribbean states, Barbados, Saint Kitts and Nevis, as well as Antigua and Barbuda, repealed laws that criminalized same-sex conduct, joining other Caribbean countries such as Trinidad and Tobago, as well as Belize. A case currently before the Supreme Court in Mauritius could get rid of its “sodomy” law. The Cook Islands became the latest country to scrap its anti-gay law, in April.

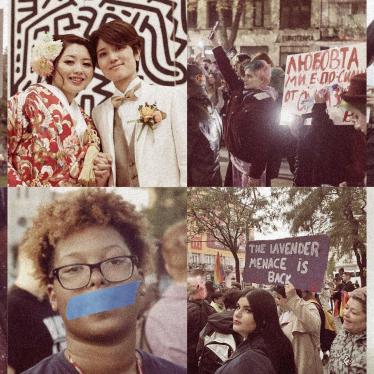

Another measure of progress is recognition for same-sex partners. In the absence of marriage or civil partnerships, same-sex couples face discrimination including in adoptions, pensions, inheritance, and hospital visitation rights. In 2001 The Netherlands was the only country in the world to recognize same-sex marriage. Now 34 countries recognize marriage and 12 allow civil partnerships.

Recently, Taiwan became the first Asian country to recognize same-sex marriage, while lawmakers in Thailand consider various options, and the Nepal supreme court ruled in favor of the foreign spouse of a Nepalese man, enabling him to live and work in Nepal. The court also urged the government to act on prior court directives on same-sex marriage.

A European Court of Justice ruling in 2018 compelled Romania, and other European countries that do not recognize same-sex spouses to ensure that foreign partners of same-sex couples have the same benefits as heterosexual partners. The absence of same-sex partnership recognition is no excuse for discriminatory treatment, the court ruled. In the world’s largest democracy, India, the supreme court is hearing a case on same-sex marriage, five years after the court decriminalized gay sex.

Other recent progress includes the United Nations appointing an independent expert to combat violence and discrimination against LGBT people worldwide. The UN LGBTI Core Group, a network of 40 states, remains actively committed to protecting and advancing LGBT rights through the UN system. Pope Francis has taken a different approach from his predecessors, emphasizing tolerance, and condemning criminal penalties for same-sex conduct. Abolishing criminal penalties, recognizing relationships, extending human rights protections are all measures of success.

But progress has not been linear. The UN appointed an expert to investigate violence and discrimination against LGBT people precisely because it is widespread and endemic.

In Eastern Europe, Russia has been at the forefront of using anti-LGBT rhetoric to shore up domestic support, positioning itself as the protector of ‘traditional values’ against a liberal West. Its ‘gay propaganda’ law even makes it an offence to portray LGBT identity as positive. It was in this climate that Chechen authorities rounded up gay men, torturing and humiliating them in front of their families.

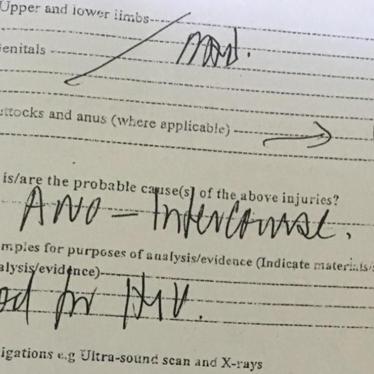

In Egypt, security forces routinely use digital platforms, including dating apps, to entrap LGBT people, arbitrarily arresting, detaining and ill-treating them. The activist Sarah Hegazy, who was arrested after photographs of her waving a rainbow flag appeared on social media, took her own life in exile in Toronto, after being tortured and sexually abused in police custody.

In Cameroon, LGBT people face arrest and ill-treatment by security forces members. Criminal laws, as on Jamaica, even when not enforced, send a tacit message that discrimination and violence against LGBT people is acceptable.

In the US, some 250 bills targeting transgender health care have come before state lawmakers in recent years. The rights of LGBT people have been at the center of ‘culture wars’ in the US ever since the anti-gay activist Anita Bryant pushed back against non-discrimination protections in Florida in the 1970s. But with majority support for same-sex marriage in the US, political attacks have shifted to pointedly focusing on transgender people, with an emphasis on an especially vulnerable group – transgender youth.

Major international events have recently focused attention on the rights of LGBT people. Russia passed its ‘gay propaganda’ law on the eve of the Sochi Winter Olympics, and the controversy overshadowed the Games. And last year the World Cup brought international attention on Qatar. Organizers were at pains to insist that all visitors would be welcome, also focusing attention on the official sanction and abuse against sexual and gender minorities there.

In a drive to boost its tourism industry, Saudi Arabia announced this May that LGBT visitors are welcome, while judges use principles of uncodified Islamic law to sanction people suspected of having sexual relations outside marriage. Is the country suggesting one set of rules for visitors, and another for citizens?

In the long arc of history, rapid progress has been made in ensuring a more equal world for LGBT people. But progress has also been uneven and has been met with strong resistance.