Human Rights Watch respectfully submits these written observations to the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (the Court) in relation to its forthcoming advisory opinion on the right to care. Our submission focuses on the right to care as it relates to and intersects with the rights of people with disabilities and older persons under international human rights law, specifically their rights to full autonomy and independent living. It does not comment on every issue the Court includes in its call for written observations; rather, it highlights elements the Court should consider when examining the right to care through the lens of the right to independent living as well as other relevant provisions that directly influence the right to make one's own choices and the principle of personal autonomy.

This submission begins by reviewing the international legal sources relevant to the interpretation of the right to support and care in the Americas region. It also reviews the general context of the disability rights movement as it relates to care services. Subsequent sections examine specific rights issues—the right of people with disabilities to provide care (Section II), families’ right to support in raising children with disabilities (Section III), people with disabilities’ right to be supported in living independently (Section IV), and the right of people with disabilities to legal capacity and systems of support and care for independent living (Section V).

I. International Legal Framework on the Right to Support and Care in the Americas

A comprehensive analysis of the content and scope of the right to support and care and how it intersects with the rights of people with disabilities and older people appropriately reflects international sources of law as well as regional treaties adopted within the framework of the Inter-American human rights system. As the Court observed in Advisory Opinion OC-1/82 (1982):

[T]he advisory jurisdiction of the Court can be exercised, in general, with regard to any provision dealing with the protection of human rights set forth in any international treaty applicable in the American States, regardless of whether it be bilateral or multilateral, whatever be the principal purpose of such a treaty, and whether or not non-Member States of the inter-American system are or have the right to become parties thereto.[1]

This means the Court may consider any international legal source to determine the content and scope of a specific right established in the American Convention on Human Rights.

In line with this principle, in addition to the Inter-American Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Persons with Disabilities, the Court should consider the right to support and care against the backdrop of other treaties that are applicable to states in the Americas, notably the United Nations (UN) Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), which all states in the Americas have ratified.

Disability Rights Model and Legal Framework

The human rights-based model of disability and legal framework emerged in response to the traditional medical model and corresponding care policies that have negatively impacted people with disabilities since the 1950s. This section summarizes traditional care policies that have harmed people with disabilities as well as the core principles of disability rights.

Harmful Traditional Care Policies

Since the 1950s, traditional care policies for people with disabilities and older persons have typically focused on caregivers and depicted care receivers as passive recipients with no decision-making power over the support and care they receive. This approach leads to “a loss of autonomy, economic disempowerment, and segregation and isolation from the rest of the community in institutions or in family homes.”[2] Such traditional conceptions also negatively impact how people with disabilities and older persons are perceived because they are portrayed as vulnerable, weak “dependents” who need to be cared for and are thus a “societal ‘burden’.”[3]

Notably, traditional care policies harm other individuals and groups as well. The global lack of sound human rights-based care policies and systems contributes to extreme levels of economic and social inequalities, with care workers and care supporters, most of whom are women who are unpaid or underpaid, too often in situations of poverty.[4] This jeopardizes already at risk communities in the Global South, like migrants and domestic workers.[5]

Eight Principles of the CRPD

The CRPD is a useful framework for the Court’s advisory opinion because it explicitly sets forth general principles to apply in understanding the scope of the rights to care, to be cared for, and to self-care for people with disabilities.

As legal theorists and other scholars have stated, its general principles are “the founding roots that spread through all the convention’s provisions and connects the various branches.”[6] The eight CRPD governing principles are:

- Respect for inherent dignity; individual autonomy, including the freedom to make one’s own choices; and people’s independence and self-determination.

- Non-discrimination.

- Full and effective participation and inclusion in society.

- Respect for difference and acceptance of people with disabilities as part of human diversity and humanity.

- Equality of opportunity.

- Accessibility.

- Equality between men and women.

- Respect for the evolving capacities of children with disabilities and respect for the rights of children with disabilities to preserve their identities.[7]

These principles were key in the development of the social model or human rights-based model of disability, which seeks to replace medicalized approaches to disability that consider people with disabilities negatively and as mere objects of rehabilitation or passive care.

The first of these principles, despite its relevance to the right to support and care, is not always implemented in practice. States have often denied people with disabilities their autonomy, including their right to make their own choices and, instead of treating them as rights holders, have considered people with disabilities as mere objects of charity, care, and assistance.

II. People with Disabilities and Older Persons’ Right to Provide Care

As mentioned, people with disabilities are commonly treated as recipients, rather than providers, of care. Sociocultural norms also play a part in stigmatizing people with disabilities as unfit to become caregivers. This notion persists despite evidence to the contrary.[8] In fact, people with disabilities, including women with disabilities, frequently are care providers.[9] However, states often do not provide people with disabilities with adequate supports to perform care giving, including parenting, tasks on an equal basis with others.[10]

International human rights law upholds the right of people with disabilities and older persons to provide care. Reading the principle of autonomy and self-determination in conjunction with the rights explicitly recognized by the CRPD, specifically the right of people with disabilities to have a family, indicates that people with disabilities should be considered as care providers. Article 23(2) of the CRPD establishes:

States Parties shall ensure the rights and responsibilities of persons with disabilities, with regard to guardianship, wardship, trusteeship, adoption of children or similar institutions … [and] shall render appropriate assistance to persons with disabilities in the performance of their child-rearing responsibilities.[11]

Furthermore, the CRPD says that a child cannot be separated from their parents based on disability (either of the child or of one or both parents).[12] As set forth in the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), a child has the right “to know and be cared by his or her parents.”[13] Children should not be separated from their parents “except when competent authorities subject to judicial review determine, in accordance with applicable law and procedures, that such separation is necessary for the best interests of the child.”[14]

Likewise, the Inter-American Convention on Protecting the Human Rights of Older Persons establishes that older persons should be provided with optimizing opportunities for “participation in social, economic, cultural, spiritual, and civic affairs,” which include the possibility of them providing care.[15]

International law does not define disability; however, according to the CRPD, people with disabilities includes people with physical, sensory, intellectual, and psychosocial impairments (mental health conditions) that can lead to exclusion when confronted with attitudinal and cultural barriers. And any person with a disability, regardless of the type, has the right to provide care. Since international law understands disability as encompassing different conditions requiring a differentiated approach to cover all situations and supports,[16] any person with any disability should be supported to provide care.

Content and Scope of the Right to Support and Care

In determining the content and scope of the right to support and care in relation to the right of people with disabilities to provide care, the Court should:

- Consider the various forms of supports that people with disabilities may need to enjoy their right to parenting or caring for their parents and other economic dependents, including supported decision-making systems and other forms of institutional, emotional, and physical support.

- Note that state policies should account for—and seek to dismantle—the various forms of discrimination faced by people with disabilities, particularly women with disabilities, including prejudice and various attitudinal barriers that consider them unfit to become caregivers.[17]

State Obligations Regarding the Right to Support and Care

In determining state obligations regarding the right to support and care in relation to the right of people with disabilities to provide care, the Court should urge states to:

- Implement specific policies encouraging the creation of support systems for people with disabilities to successfully become carers, such as policies providing for adaptive housing, coaching, and counseling; easy access to information; render appropriate assistance to parents and legal guardians in child-rearing[18]; and training on how to perform parenting or other daily care activities such as changing a child, feeding, and nurturing.[19]

- Ensure that the policies developed do not perpetuate the gendered distribution of unpaid care work.[20]

III. Families’ Right to Support in Raising Children with Disabilities

The CRPD establishes the right of children with disabilities to, as much as possible, know their parents and be cared for by them.[21] When this is not possible, states should “undertake every effort to provide alternative care within the wider family, and failing that, within the community in a family setting.”[22]

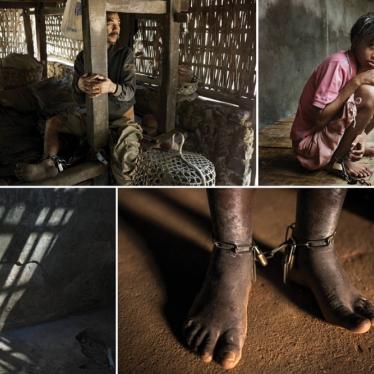

Harmful Impacts of Residential Institutions

The right of children with disabilities to care is crucial in the Americas, where many countries still institutionalize children with disabilities when their nuclear family cannot care for them because they lack adequate support to do so. Children with disabilities have been institutionalized and have experienced accompanying human rights abuses not only in the Americas, but also in Africa, Asia, Europe, and Central Asia. Human Rights Watch has documented this practice in Armenia, Brazil, Croatia, Ghana, India, Indonesia, Japan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Nigeria, Russia, Serbia, Somaliland, and Ukraine.[23]

Numerous observational studies have found that placing children in institutional settings, irrespective of their material conditions, where the provided care focuses only on children’s basic needs without a one-to-one relationship, is detrimental to their emotional, cognitive, physical, and social development.[24] According to the World Health Organization and UNICEF, institutional environments can cause “developmental delays and irreversible psychological damage due to lack of consistent caregiver input, inadequate stimulation, lack of rehabilitation and poor nutrition.” Such settings further negatively impact the many children with disabilities who require access to additional learning opportunities or specialized services like rehabilitation, which institutions often lack.[25]

Institutionalization affects children of different ages differently. Child development specialists have found that the institutionalization of babies harms their early brain development and puts them at risk of attachment disorder, developmental delays, and neural atrophy.[26] Regarding the institutionalization of adolescents, the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child noted:

There is significant evidence of poor outcomes for adolescents in large long-term institutions.... These adolescents experience lower educational attainment, dependency on social welfare, and higher risk of homelessness, imprisonment, unwanted pregnancy, early parenthood, substance misuse, self-harm, and suicide.[27]

Family-based Settings as Alternatives

Family-based settings are a much better option than institutional ones for children with disabilities. Studies appear to show that children moved from an institution into a family-based environment demonstrate signs of improvement in their intellectual functioning and attachment patterns, reduced signs of emotional withdrawal, and reduced prevalence of mental health conditions.[28]

While some countries in the Americas, like Brazil, have developed foster care alternatives for children who lack family support for different reasons, such as poverty and marginalization, these options are not accessible for children with disabilities.[29]

Children with disabilities are further affected by more difficulties in being adopted, a problem stemming from entrenched prejudice and a lack of proper support to adoptive families to raise children with disabilities.[30]

Content and Scope of the Right to Support and Care

In determining the content and scope of the right to support and care in relation to children with disabilities, the Court should consider children’s right to be cared for by their families or in family settings to be a crucial part of the right to support and care.[31] The CRPD prohibits separating a child from parents “on the basis of a disability of either the child or both of the parents,” and requires states, in case the immediate family is unable to care for a child with disabilities, to “undertake every effort to provide alternative care with the wider family, and failing that, within the community in a family setting.”[32] Children should only be placed in residential institutions when other alternatives are not available or if such placement would prevent the separation of siblings. If a child is placed in an institution, it must only be for a limited duration and with the goal of family reunification or placement in appropriate long-term alternative care. Infants and children under the age of three should never be placed in institutions; instead, they should be placed in family settings, such as emergency foster care.

State Obligations Regarding the Right to Support and Care

In determining state obligations regarding the right to support and care in relation to children with disabilities, the Court should urge states to support families in caring for children with disabilities, including those with high support requirements. Support should be given by creating robust care alternatives such as professional personal assistance that reflect the specific requirements children have, including cognitive, behavioral, or mental health support. This would be instrumental for preventing parents institutionalizing children with disabilities.[33]

Likewise, when nuclear families are unable to care for children even with support, states should establish and invest in foster care systems for children, including those with disabilities, who lack family support. Foster care alternatives should be inclusive of children with disabilities, which states can promote by providing additional resources to foster families. States should also actively promote the possibility of children with disabilities being adopted on an equal basis with other children without disabilities, including through public education to eliminate prejudice and the provision of additional resources to adoptive families. Some studies have shown that children with disabilities experienced more difficulties in being adopted: this stems from entrenched prejudice and lack of proper support to adoptive families to raise children with disabilities.

IV. People with Disabilities and Older Persons’ Right to be Supported in Living Independently

People with disabilities, including older persons with disabilities, have the right to live independently as well as the right to be supported in enjoying this right.[34] Specifically, as the Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities has emphasized, people with disabilities, including older persons with disabilities, should be able to “exercise choice and control over their lives and make all decisions concerning their lives.”[35] This right should apply to all older persons.[36]

Regarding disability rights, disability rights advocates have regularly emphasized the need for support and care systems to respect recipients’ agency and autonomy to overcome the power imbalance between them and their supporters/caregivers. This would address the traditionally paternalistic practices and attitudes toward people with disabilities, both of which heighten their risk of violence, exploitation, and abuse.

Regarding women’s rights, historically, women have been responsible for supporting people with disabilities. Their provision of care has been unrecognized labor and subject to abusive practices, like being underpaid or unpaid for the support they provide.[37]

This situation necessitates a shift to a paradigm in which support and care is given through different alternatives. These support alternatives should be consistent with people with disabilities and older persons’ right to independent living and inclusion in the community. Unfortunately, current care policies still present initiatives, like institutionalization, that do not honor agency and the right to live independently in the community. The institutionalization of people with disabilities, including children and older persons with disabilities, is inconsistent with the right to independence and autonomy and invariably entails other human rights violations. The Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities observes that the “systematic realization of the right to independent living in the community requires structural changes,” including phasing out institutionalization. It provides further guidance that:

No new institutions may be built by States parties, nor may old institutions be renovated beyond the most urgent measures necessary to safeguard residents’ physical safety. Institutions should not be extended [and] new residents should not enter in place of those that leave.[38]

However, states have continued building institutions, as well as other facilities that are not called “institutions” but have the same structure as institutions, such as small group homes, where people are placed without their consent.

In the Americas, Mexico’s most recent national strategy to implement the right to care establishes the need to build “long-term residences” for people with disabilities and older persons.[39] Similarly, Uruguay’s 2020-2025 plan for care policies provides for the creation of new “institutions” (long-term residences) for people with disabilities.[40]

Abuses in Institutional Settings

Human Rights Watch has extensively documented abuses stemming from the institutionalization of people with disabilities and older persons. While there are many forms of institutionalization, they all deprive the institutionalized person of control and choice over their living arrangements. According to the Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, institutionalization’s common features include:

[O]bligatory sharing of assistants with others and no or limited influence over by whom one has to accept assistance, isolation and segregation from independent life within the community, lack of control over day-to-day decisions, lack of choice over whom to live with, rigidity of routine irrespective of personal will and preferences, identical activities in the same place for a group of persons under a certain authority, a paternalistic approach in service provision, supervision of living arrangements and usually also a disproportion in the number of persons with disabilities living in the same environment.[41]

Institutional care is also characterized by many or all of the following elements: separation from families and the wider community; confinement to groups homogeneous in age and disability; de-personalization; overcrowding; instability of caregiver relationships; lack of caregiver responsiveness; repetitive, fixed daily timetables for sleep, eating, and hygiene routines not tailored to people’s needs and preferences; and sometimes, insufficient material resources.[42]

Human Rights Watch has investigated the situation of people with disabilities in institutions in Armenia, Brazil, Croatia, Ghana, India, Indonesia, Japan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Nigeria, Russia, Serbia, Somaliland, and Ukraine and uncovered various human rights violations.[43]

Likewise Human Rights Watch has investigated the impact institutionalization has on the rights of older persons in Australia and the Unites States.[44]

Living in institutions causes emotional hardship, particularly for those who remain there continuously. Institutions also have serious shortcomings in how they prepare children to live independently as adults.

In Brazil, thousands of people with disabilities have been placed in institutions. Human Rights Watch found that most people enter as children and continue to live there through adulthood, sometimes for their entire lives. In these institutions, they may face neglect, inhumane conditions, and abuse, with little respect for their dignity and individual needs or preferences. These high numbers of institutionalized people result from the Brazilian government’s failure to provide sufficient support for children and adults with disabilities to live independently or in a family setting.

Organizations of People with Disabilities and Older Persons Should Be Involved in the Administration and Provision of Support and Services

A key principle of international disability rights law concerns the need for close participation of people with disabilities and older persons in policies that affect them. Moreover, to reflect the importance of people with disabilities’ inclusion in all matters, the disability rights movement’s motto “nothing about us without us” has evolved into “nothing without us.”[45]

Content and Scope of the Right to Support and Care

In determining the content and scope of the right to support and care in relation to the rights of people with disabilities and older persons to be supported in living independently, we encourage the Court to emphasize the need for policies that would enable such organizations of people with disabilities and organizations of older persons to participate closely in the provision of support and care.

State Obligations Regarding the Right to Support and Care

In determining state obligations regarding the right to support and care, the Court should read it through the lens of people with disabilities and older persons’ right to independent living and inclusion in the community. It should recall the abuses fueled by institutionalization as well as the Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities’ call for deinstitutionalization.

In conjunction with deinstitutionalization, states should provide a range of individualized support services, such as psychological counseling, assistance in securing housing or shelter, personal assistance services, supported decision making, transportation referral and assistance, physical therapy, mobility training, rehabilitation technology, recreation, and other services necessary to improve the ability of individuals with disabilities with high support requirements to function independently in their family or community and/or work or continue working.[46] All services should allow for personal choice and control of services being provided. These services will help realize the full inclusion of people with disabilities and older persons in society and prevent their isolation and segregation from others in the community.

To implement the principle of close participation of people with disabilities in support and care, states should implement the Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities’ guidelines on how to better achieve meaningful participation of organizations of people with disabilities in different policies.[47]

States should create robust mechanisms to enable organizations of people with disabilities to be actors in the provision of support and care services. Promoting their participation could be achieved through specific funding for organizations for people with disabilities to become focal points for needs assessments, data gathering, and community service referrals, among others.

States should raise awareness about the autonomy of people with disabilities to eliminate stereotypes portraying people with disabilities and older persons only as recipients of care. States should also raise awareness about the negative impact of gender and ageist stereotypes in providing care and receiving care and support, and develop programs and policies to eliminate such stereotypes.

V. People with Disabilities and Older Persons’ Right to Legal Capacity and Systems of Support and Care for Independent Living

Legal capacity is considered a threshold right because it is instrumental to the enjoyment of other fundamental rights.[48] With respect to the right to support and care, the legal capacity of people with disabilities and older persons is fundamentally linked to the principles of equality and non-discrimination. Thus, states parties to the CRPD must ensure that people with disabilities enjoy the right to full legal capacity on an equal basis with others and the right to receive the support they need to make their own choices and direct their own lives. However, all too often, people with disabilities, particularly those with intellectual, cognitive, or psychosocial disabilities, are denied the power to make independent decisions and have their decisions legally recognized.

Abuses Related to Denial of Legal Capacity

Human Rights Watch investigated abuses against people with disabilities stemming from the denial of their legal capacity in Croatia and Serbia, which are illustrative of the global problem.

In Croatia, as of 2014, 18,000 people with intellectual and psychosocial disabilities had been deprived of their legal capacity.[49] Human Rights Watch’s interviews with people with intellectual or psychosocial disabilities revealed that the denial of the right to legal capacity of people with disabilities continues to limit their other human rights, including the right to liberty, the right to marry and found a family, parental rights, the right to give consent to medical treatment, the right to choose where and with whom to live on an equal basis with others, and the right to vote.[50]

In Serbia, as of December 2015, 19,000 people with disabilities had been stripped of their right to legal capacity and placed under guardianship.[51] Human Rights Watch documented cases of young women with disabilities who had been deprived of their legal capacity and subjected to invasive medical interventions, including termination of pregnancy with a guardian’s consent but without the woman’s own free and informed consent.[52]

Positively, some Americas countries, like Argentina,[53] Brazil,[54] Colombia,[55] Costa Rica,[56] Mexico,[57] and Peru,[58] have started developing legislative reforms to ensure that people with disabilities and older people have the right to legal capacity and supported decision-making to exercise their rights.

Content and Scope of the Right to Care

In determining the content and scope of the right to care in relation to legal capacity and systems of support and care for independent living, the Court should note that legal capacity is a threshold right. It should also recognize that people with disabilities and older persons require full legal capacity on an equal basis with others and the right to receive the support they need to make their own choices and direct their own lives in order to experience the principles of equality and non-discrimination.

State Obligations Regarding the Right to Care

In the context of state obligations regarding support and care systems, the Court should urge states to:

- Ensure that adults receiving care and support can control, direct, and manage their own systems of support and care. The Court should also clarify that states have an obligation to ensure that private sector providers of care comply with the elements outlined below.

- Ensure that people with disabilities and older persons have affordable, accessible, appropriate, integrated, quality, timely, and holistic support and care services which are adapted to their individual needs, independent of and unrelated to the income of their family members.

- Ensure that adults have the opportunity to make legally binding documents on the type of care and support they would like and who provides it, should it be required at a future point in time.

- Ensure research, design, development, and monitoring of care and support services is carried out with the involvement of people with disabilities and older persons themselves and in accordance with international ethical research standards.

- Ensure people with disabilities and older persons have access to information about available support and care services so they can effectively use, select, and opt out of care and support services, and that people with disabilities and older persons have access to information and training, including digital and technical skills, so that they can evaluate the risks and benefits of different care and support services and make informed decisions.

- Ensure people with disabilities and older persons have access to effective dispute resolution, complaint mechanisms, and administrative and/or judicial processes to seek redress for practices that restrict their liberty and autonomy and do not respect their will and preferences or in situations where violations occur.

- Establish supported decision-making models and other systems of support and care that are consistent with the right to independent living and inclusion in the community and that incorporate the following elements:

- Center principles of equality and non-discrimination. States should make available support systems for all types of disabilities, regardless of the levels of support required by the person, so they can fully enjoy the right, including but not limited to the option of having animal and/or human personal assistance, and access to different means, such as accessible infrastructure, accessible housing, and referral centers.

- Recognize the full legal capacity of people with disabilities and older persons and give them decision-making powers over their systems of support, including through supported decision-making. States should establish a range of mechanisms for supported decision-making, in accordance with article 12 of the CRPD and article 30 of the Inter-American Convention on Protecting the Human Rights of Older Persons.

- Include, as a form of support, access to supported decision-making for people to direct the support they get from their supporter. For example, even if a person has a supporter to help them buy groceries, they may also need another person to explain to the supporter exactly what they need and want.

- Center a broader notion of autonomy in support and care policies. Policies and systems should not exclusively frame autonomy as a person’s ability to perform an act themselves. Instead, they should adopt a more expansive understanding of autonomy as also covering situations where a person controls their own environment with the support of another person.

- Include diverse components as part of support and care. Support and care should cover a variety of components that enable people with disabilities and older persons to engage in different types of activities—such as support for physical activities, understanding information, and communicating decisions and reminding them of the obligations they need to fulfill—related to the enjoyment of their rights on an equal basis with others, including transportation, leisure activities, education, parenting, employment, and household maintenance. These components should also entail decision-making supports and accommodations, either as a form of support itself or as one that enable people with disabilities and older persons to exercise their legal capacity and direct their own support systems.

- Envision policies that are not necessarily targeted toward individual support, but rather universal access, and that could enable people with disabilities and older persons to autonomously enjoy different activities. For instance, states should invest in accessible transport and housing.

- Integrate gender sensitivity and inclusivity into support and care policies. Policies should respect gender identity and expression, and all forms of support and care for people with disabilities and older persons should honor their autonomy and self-identification.

- Consider the views of children with disabilities, to ensure their best interests are taken into account. Children with disabilities have the right to express their views freely on all matters affecting them, which includes what care they receive, and to have their views given due weight in accordance with their age and maturity, on an equal basis with other children, and to be provided with disability and age-appropriate assistance to realize that right.[59] A child has the right to be consulted as well as to be fully informed about their care options.[60]

Conclusion

Human Rights Watch hopes that our analysis can assist the Court in defining the content and scope of the right to care, as well as the corresponding state obligations regarding people with disabilities and older people. We would welcome the opportunity to discuss these issues further with the Court.

[1] Inter-American Court of Human Rights, “Advisory Opinion OC-1/82,” September 24, 1982, https://www.corteidh.or.cr/docs/opiniones/seriea_01_ing1.pdf (accessed November 6, 2023), para. 52.

[2] Human Rights Council, “Support systems to ensure community inclusion of persons with disabilities, including as a means of building forward better after the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic: Report of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights,” A/HRC/52/52, January 4, 2023, https://www.ohchr.org/en/documents/thematic-reports/ahrc5252-support-systems-ensure-community-inclusion-persons-disabilities (accessed November 6, 2023), para. 6.

[3] Ibid.

[4] International Labour Organization (ILO), “Care work and care jobs for the future of decent work,” 2018, https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---dcomm/---publ/documents/publication/wcms_633135.pdf (accessed November 6, 2023), p. 146.

[5] Idem.

[6] Marianne Schulze, “Understanding The UN Convention On The Rights of Persons with Disabilities,” Handicap International, July 2010, https://www.internationaldisabilityalliance.org/sites/default/files/documents/hi_crpd_manual2010.pdf (accessed November 6, 2023).

[7] Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), art. 2.

[8] Linda Sanabria, “The Hard Reality of Discrimination Against Parents with Disabilities,” Accessibility.com, July 8, 2022, https://www.accessibility.com/blog/the-cruel-reality-of-discrimination-against-parents-with-disabilities (accessed November 6, 2023).

[9] Arielle Dance, “Yes, Disabled People Can Be Parents,” Medium, February 2, 2023, https://medium.com/rewriting-the-narrative/yes-disabled-people-can-be-parents-f8ca60b96491 (accessed November 6, 2023).

[10] The Arc, “Parents with Intellectual and/or Developmental Disabilities,” April 7, 2019, https://thearc.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/Parents-with-Intellectual-and_or-Developmental-Disabilities.pdf (accessed November 6, 2023).

[11] CRPD, art. 23(2).

[12] CRPD, art. 23(4).

[13] Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), art. 7(2).

[14] CRC, art. 9(1).

[15] Inter-American Convention on Protecting the Human Rights of Older Persons, art. 2.

[16] CRPD, Preamble (j).

[17] Human Rights Watch has documented instances in which deaf women are prohibited from parenting. See: Human Rights Watch, “Better to Make Yourself Invisible: Family Violence against People with Disabilities in Mexico,” June 4, 2020, https://www.hrw.org/report/2020/06/04/better-make-yourself-invisible/family-violence-against-people-disabilities-mexico. In the report, several cases were documented of women being deprived of the rights to become mothers. Graciela, a 30-year-old woman from Monterrey, Nuevo León, who is deaf, told Human Rights Watch how her parents beat her while she lived with them and later petitioned for custody of her son, their grandchild, claiming Graciela was unfit to parent due to her disability.

[18] CRC, art. 18(2).

[19] National Research Center for Parents with Disabilities, “Parenting Tips and Strategies from Parents with Disabilities,” Undated, https://heller.brandeis.edu/parents-with-disabilities/support/parenting-tips-strategies/index.html (accessed November 6, 2023).

[20] CRC, art. 18(1); Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), arts. 5(a)(b), 11.

[21] CRPD, art. 18(2); CRC, art. 7(1).

[22] CRPD, art. 23(5); CRC, art. 20.

[23] Human Rights Watch, “When Will I Get to Go Home?: Abuses and Discrimination against Children in Institutions and Lack of Access to Quality Inclusive Education in Armenia,” February 22, 2017, https://www.hrw.org/report/2017/02/22/when-will-i-get-go-home/abuses-and-discrimination-against-children-institutions; “They Stay until They Die: A Lifetime of Isolation and Neglect in Institutions for People with Disabilities in Brazil,” May 23, 2018, https://www.hrw.org/report/2018/05/23/they-stay-until-they-die/lifetime-isolation-and-neglect-institutions-people; “Croatia: Locked Up and Neglected,” October 6, 2014, https://www.hrw.org/news/2014/10/06/croatia-locked-and-neglected; “Like a Death Sentence: Abuses against Persons with Mental Disabilities in Ghana,” October 2, 2012, https://www.hrw.org/report/2012/10/02/death-sentence/abuses-against-persons-mental-disabilities-ghana; “Treated Worse than Animals: Abuses against Women and Girls with Psychosocial or Intellectual Disabilities in Institutions in India,” December 3, 2014, https://www.hrw.org/report/2014/12/03/treated-worse-animals/abuses-against-women-and-girls-psychosocial-or-intellectual; “Living in Hell: Abuses against People with Psychosocial Disabilities in Indonesia,” March 21, 2016, https://www.hrw.org/report/2016/03/20/living-hell/abuses-against-people-psychosocial-disabilities-indonesia; “Without Dreams: Children in Alternative Care in Japan,” May 1, 2014, https://www.hrw.org/report/2014/05/01/without-dreams/children-alternative-care-japan; “Kazakhstan: Children in Institutions Isolated, Abused,” July 17, 2019, https://www.hrw.org/news/2019/07/17/kazakhstan-children-institutions-isolated-abused; “Insisting on Inclusion: Institutionalization and Barriers to Education for Children with Disabilities in Kyrgyzstan,” December 10, 2020, https://www.hrw.org/report/2020/12/10/insisting-inclusion/institutionalization-and-barriers-education-children; “Nigeria: People With Mental Health Conditions Chained, Abused,” November 11, 2019, https://www.hrw.org/news/2019/11/11/nigeria-people-mental-health-conditions-chained-abused; “Abandoned by the State: Violence, Neglect, and Isolation for Children with Disabilities in Russian Orphanages,” September 15, 2014, https://www.hrw.org/report/2014/09/15/abandoned-state/violence-neglect-and-isolation-children-disabilities-russian; “It is My Dream to Leave This Place: Children with Disabilities in Serbian Institutions,” June 8, 2016, https://www.hrw.org/report/2016/06/08/it-my-dream-leave-place/children-disabilities-serbian-institutions; “Chained Like Prisoners: Abuses Against People with Psychosocial Disabilities in Somaliland,” October 26, 2015, https://www.hrw.org/report/2015/10/26/chained-prisoners/abuses-against-people-psychosocial-disabilities-somaliland; “We Must Provide a Family, Not Rebuild Orphanages: The Consequences of Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine for Children in Ukrainian Residential Institutions,” March 13, 2023, https://www.hrw.org/report/2023/03/13/we-must-provide-family-not-rebuild-orphanages/consequences-russias-invasion.

[24] National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, “The Science of Neglect: The Persistent Absence of Responsive Care Disrupts the Developing Brain: Working Paper No. 12,” 2012, https://developingchild.harvard.edu/resources/the-science-of-neglect-the-persistent-absence-of-responsive-care-disrupts-the-developing-brain/ (accessed November 6, 2023); Anne E. Berens & Charles A. Nelson, “The Science of early adversity: is there a role for large institutions in the care of vulnerable children?,” The Lancet vol. 386, n. 9991, pp. 388-398, July 25, 2015, https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(14)61131-4/fulltext (accessed November 6, 2023).

[25] World Health Organization (WHO) & UNICEF, “Early Childhood Development and Disability: A discussion paper,” 2012, http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/75355/1/9789241504065_eng.pdf (accessed November 6, 2023); Mary Dozier et al., “Institutional Care for Young Children: Review of Literature and Policy Implications,” Social Issues and Policy Review vol. 6, n. 1, pp. 1-25, March 5, 2012, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3600163/ (accessed November 6, 2023).

[26] Georgette Mulheir, “Deinstitutionalisation step by step: Challenges and opportunities for children,” Lumos, February 12, 2015, https://www.eesc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/resources/docs/1100_2015-02-12_mulheir.pdf (accessed November 6, 2023); Kevin Browne, “The Risk of Harm to Young Children in Institutional Care,” Better Care Network & Save the Children, 2009, https://resourcecentre.savethechildren.net/document/risk-harm-young-people-institutional-care/ (accessed November 6, 2023); Inge Bretherton, “The origins of attachment theory: John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth,” Developmental Psychology vol. 28, pp. 759-775, 1992, http://www.psychology.sunysb.edu/attachment/online/inge_origins.pdf (accessed November 6, 2023); Serena Cherry Flaherty & Lois S. Sadler, “A Review of Attachment Theory in the Context of Adolescent Parenting,” Journal of Pediatric Health Care vol. 25, n. 2, pp. 114-121, 2011, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3051370/ (accessed November 6, 2023).

[27] Committee on the Rights of the Child, “General comment No. 20 (2016) on the implementation of the rights of the child during adolescence,” CRC/C/GC/20, December 6, 2016, https://www.ohchr.org/en/documents/general-comments-and-recommendations/general-comment-no-20-2016-implementation-rights (accessed November 6, 2023), para. 52.

[28] Rebecca Johnson, Kevin Browne & Catherine Hamilton-Giachritsis, “Young children in institutional care at risk of harm,” Trauma Violence Abuse vol. 7, n. 1, pp. 34-60, January 2006, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16332980/ (accessed November 6, 2023). For an analysis on the benefits of foster care and other alternatives to institutionalization, please see: Better Care Network, “Ending Child Institutionalization,” Undated, https://bettercarenetwork.org/library/principles-of-good-care-practices/ending-child-institutionalization.

[29] Human Rights Watch, “They Stay until They Die,” https://www.hrw.org/report/2018/05/23/they-stay-until-they-die/lifetime-isolation-and-neglect-institutions-people.

[30] Blake Connell, “Some Parents Are More Equal than Others: Discrimination against People with Disabilities under Adoption Law,” Laws vol. 6, n. 3, 2017, https://www.mdpi.com/2075-471X/6/3/15 (accessed November 6, 2023).

[31] The preamble to the CRC recognizes a “family environment” as the natural environment for the growth and well-being of all children, without discrimination, “in an atmosphere of happiness, love, and understanding.”

[32] CRPD, art. 23(5).

[33] CRPD, Preamble, arts. 7, 19.

[34] CRPD, arts. 3, 5, 12, 19; Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, “General comment No. 5 (2017) on living independently and being included in the community,” CRPD/C/GC/5, October 27, 2017, https://www.ohchr.org/en/documents/general-comments-and-recommendations/general-comment-no5-article-19-right-live (accessed November 6, 2023).

[35] Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, CRPD/C/GC/5, https://www.ohchr.org/en/documents/general-comments-and-recommendations/general-comment-no5-article-19-right-live, para. 16(a).

[36] The right to housing, which the Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights has described as “the right to live somewhere in security, peace, and dignity,” encompasses the right of older people to live independently in the community. As the UN Independent Expert on the enjoyment of all human rights by older persons has observed, “Older persons have an equal right with others to decide where to live and with whom, and not to be forced into a particular living arrangement. This right includes having the necessary means and support enabling them to make decisions and live their lives in accordance with their wills and preferences.” See: Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, “General Comment No. 4: The Right to Adequate Housing (Art. 11 (1) of the Covenant),” E/1992/23, December 13, 1991, https://www.refworld.org/pdfid/47a7079a1.pdf (accessed November 6, 2023), para. 7; Human Rights Council, “Report of the Independent Expert on the enjoyment of all human rights by older persons,” A/HRC/39/50, July 10, 2018, https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/G18/210/00/PDF/G1821000.pdf (accessed November 6, 2023), para. 67.

[37] ILO, “Care work and care jobs for the future of decent work,” https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---dcomm/---publ/documents/publication/wcms_633135.pdf.

[38] Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, CRPD/C/GC/5, https://www.ohchr.org/en/documents/general-comments-and-recommendations/general-comment-no5-article-19-right-live, paras. 28-37, 49.

[39] INMUJERES & ONU Mujeres, “Bases para una estrategia nacional de cuidados,” November 2018, https://mexico.unwomen.org/sites/default/files/Field%20Office%20Mexico/Documentos/Publicaciones/2019/BASES%20PARA%20UNA%20ESTRATEGIA%20NACIONAL%20DE%20CUIDADOS%202018%20web1.pdf (accessed November 6, 2023).

[40] Ministerio de Desarrollo Social, “Plan Nacional de Cuidados 2021-2025,” July 8, 2021, https://www.gub.uy/ministerio-desarrollo-social/sites/ministerio-desarrollo-social/files/documentos/publicaciones/JUNIO_PLAN DE CUIDADOS 2021-2025.pdf (accessed November 6, 2023).

[41] Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, CRPD/C/GC/5, https://www.ohchr.org/en/documents/general-comments-and-recommendations/general-comment-no5-article-19-right-live, para. 16(c).

[42] Human Rights Watch, “When Will I Get to Go Home?,” https://www.hrw.org/report/2017/02/22/when-will-i-get-go-home/abuses-and-discrimination-against-children-institutions; Arlene S. Kanter, “The Development of Disability Rights Under International Law: From Charity to Human Rights,” LONDON: Routledge, 2015.

[43] Human Rights Watch, “When Will I Get to Go Home?: Abuses and Discrimination against Children in Institutions and Lack of Access to Quality Inclusive Education in Armenia,” February 22, 2017, https://www.hrw.org/report/2017/02/22/when-will-i-get-go-home/abuses-and-discrimination-against-children-institutions; “They Stay until They Die: A Lifetime of Isolation and Neglect in Institutions for People with Disabilities in Brazil,” May 23, 2018, https://www.hrw.org/report/2018/05/23/they-stay-until-they-die/lifetime-isolation-and-neglect-institutions-people; “Croatia: Locked Up and Neglected,” October 6, 2014, https://www.hrw.org/news/2014/10/06/croatia-locked-and-neglected; “Like a Death Sentence: Abuses against Persons with Mental Disabilities in Ghana,” October 2, 2012, https://www.hrw.org/report/2012/10/02/death-sentence/abuses-against-persons-mental-disabilities-ghana; “Treated Worse than Animals: Abuses against Women and Girls with Psychosocial or Intellectual Disabilities in Institutions in India,” December 3, 2014, https://www.hrw.org/report/2014/12/03/treated-worse-animals/abuses-against-women-and-girls-psychosocial-or-intellectual; “Living in Hell: Abuses against People with Psychosocial Disabilities in Indonesia,” March 21, 2016, https://www.hrw.org/report/2016/03/20/living-hell/abuses-against-people-psychosocial-disabilities-indonesia; “Without Dreams: Children in Alternative Care in Japan,” May 1, 2014, https://www.hrw.org/report/2014/05/01/without-dreams/children-alternative-care-japan; “Kazakhstan: Children in Institutions Isolated, Abused,” July 17, 2019, https://www.hrw.org/news/2019/07/17/kazakhstan-children-institutions-isolated-abused; “Insisting on Inclusion: Institutionalization and Barriers to Education for Children with Disabilities in Kyrgyzstan,” December 10, 2020, https://www.hrw.org/report/2020/12/10/insisting-inclusion/institutionalization-and-barriers-education-children; “Nigeria: People With Mental Health Conditions Chained, Abused,” November 11, 2019, https://www.hrw.org/news/2019/11/11/nigeria-people-mental-health-conditions-chained-abused; “Abandoned by the State: Violence, Neglect, and Isolation for Children with Disabilities in Russian Orphanages,” September 15, 2014, https://www.hrw.org/report/2014/09/15/abandoned-state/violence-neglect-and-isolation-children-disabilities-russian; “It is My Dream to Leave This Place: Children with Disabilities in Serbian Institutions,” June 8, 2016, https://www.hrw.org/report/2016/06/08/it-my-dream-leave-place/children-disabilities-serbian-institutions; “Chained Like Prisoners: Abuses Against People with Psychosocial Disabilities in Somaliland,” October 26, 2015, https://www.hrw.org/report/2015/10/26/chained-prisoners/abuses-against-people-psychosocial-disabilities-somaliland; “We Must Provide a Family, Not Rebuild Orphanages: The Consequences of Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine for Children in Ukrainian Residential Institutions,” March 13, 2023, https://www.hrw.org/report/2023/03/13/we-must-provide-family-not-rebuild-orphanages/consequences-russias-invasion.

[44] Human Rights Watch, “Fading Away: How Aged Care Facilities in Australia Chemically Restrain Older People with Dementia,” October 15, 2019, https://www.hrw.org/report/2019/10/15/fading-away/how-aged-care-facilities-australia-chemically-restrain-older-people; “US: Concerns of Neglect in Nursing Homes,” March 25, 2021, https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/03/25/us-concerns-neglect-nursing-homes.

[45] Alexis Buettgen & Ezra Zubrow, “Nothing Without Us: Disability, Critical Thought, and Social Change in a Globalizing World,” Handbook of Disability pp. 1-16, July 20, 2023, https://link.springer.com/referenceworkentry/10.1007/978-981-16-1278-7_99-1 (accessed November 6, 2023).

[46] Administration for Community Living, “Centers for Independent Living,” Undated, https://acl.gov/programs/aging-and-disability-networks/centers-independent-living (accessed November 6, 2023).

[47] Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, “General comment No. 7 (2018) on the participation of

persons with disabilities, including children with disabilities, through their representative organizations, in the implementation and monitoring of the Convention,” CRPD/C/GC/7, November 9, 2018, https://www.ohchr.org/en/documents/general-comments-and-recommendations/general-comment-no7-article-43-and-333-participation (accessed November 6, 2023).

[48] Human Rights Watch, “Letter to Mexico Federal Congress Regarding Full Legal Capacity Recognition,” May 17, 2023, https://www.hrw.org/news/2023/05/17/letter-mexico-federal-congress-regarding-full-legal-capacity-recognition.

[49] Human Rights Watch, “Croatia: Locked Up and Neglected,” https://www.hrw.org/news/2014/10/06/croatia-locked-and-neglected.

[50] Ibid.

[51] Human Rights Watch, “It is My Dream to Leave This Place,” https://www.hrw.org/report/2016/06/08/it-my-dream-leave-place/children-disabilities-serbian-institutions.

[52] Ibid.

[53] Código Civil y Comercial de la Nación, Ley n. 26.994, 2014.

[54] Ley Brasilera de Inclusión de las Personas con Discapacidad, Ley n. 13.146, 2015.

[55] Ley n. 1.996, 2019.

[56] Ley n. 9.379, 2016.

[57] Código Nacional de Procedimientos Civiles y Familiares, 2023.

[58] Decreto Legislativo n. 1.384, 2018.

[59] CRPD, art. 7; CRC, art. 12(1).

[60] United Nations General Assembly, “Guidelines for the Alternative Care of Children,” A/RES/64/142, February 24, 2010, https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N09/470/35/PDF/N0947035.pdf (accessed November 6, 2023), paras. 57, 64.