Summary

Luciana, 31, and Juan Herrera (pseudonyms), 32, left Venezuela in 2023, leaving their three children, ages 2, 6, and 11, behind. In March 2023, they crossed the Darién Gap, a swampy jungle at the Colombia-Panama border, with the hope of going to the United States. In their five-day walk across the jungle, a group of men wearing hoods and black clothes assaulted them, demanding US$100 from each person in their group. The men had guns and machetes, Juan and Luciana said. “Look straight or we will kill you,” one told the couple. The armed men took another young woman aside, letting her go once her brother paid. Frightened, she ran away and almost fell off a cliff.

Over half a million people crossed the Darién Gap in 2023, often heading to the United States. During their journey through this difficult terrain, Venezuelans, Haitians, and Ecuadorians, as well as people from Asia and Africa, have experienced serious abuses, including sexual violence. Dozens, if not hundreds, have lost their lives or gone missing trying to cross. Many have never been found.

Human Rights Watch visited the Darién Gap four times between April 2022 and June 2023 and interviewed almost 300 people. Human Rights Watch documented why migrants and asylum seekers flee their own countries and are reluctant to stay in other countries in South America; how criminal groups abuse and exploit them on the way; and where Colombia’s and Panama’s policies fall short in assisting, protecting, and investigating abuses against them.

This report, part of a series of Human Rights Watch reports on migration via the Darién Gap, focuses on Colombia’s and Panama’s responses to migration across their border. It identifies specific shortcomings in their efforts to protect and assist these people—including those at higher risk, such as unaccompanied children—as well as to investigate abuses against them. The report provides concrete recommendations to the governments of Colombia and Panama on how to address these shortcomings and to donor governments, the United Nations and regional bodies, and humanitarian organizations on how to support and cooperate with Colombia and Panama in these efforts.

Our findings show that Colombia and Panama are failing to effectively protect the international human rights of migrants and asylum seekers transiting through the Darién Gap. Under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the American Convention on Human Rights (ACHR), treaties Colombia and Panama have ratified, governments have an obligation to protect the right to life and physical integrity of people in their territory, including transiting migrants and asylum seekers, and to investigate violations effectively, promptly and thoroughly. Additionally, both governments have an obligation under the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights and the Protocol of San Salvador to take appropriate steps to ensure access to food, water, and essential health services for all people in their territory without discrimination.

In Colombia, the government lacks a clear strategy to safeguard the rights of migrants and asylum seekers crossing the Darién Gap. The limited government presence in the region effectively leaves these people to be preyed upon by the Gulf Clan, an armed group involved in drug trafficking, which controls the movement of migrants and asylum seekers and profits from their desperation and vulnerability. Colombian authorities’ efforts to investigate crimes and dismantle the Gulf Clan in the region have yielded minimal results. The government lacks reliable information on the number of migrants crossing and their humanitarian needs, impacting authorities’ ability to effectively ensure the rights to access food, water and sanitation. Mayor’s offices from departing municipalities lack sufficient expertise, personnel, and resources to respond to the increased influx of migrants and asylum seekers.

The Panamanian government implements a strategy of “controlled flow” (or “humanitarian flow”) on the other side of the Darién Gap. The policy appears focused on restricting the free movement of migrants and asylum seekers within Panama and seeking their swift exit to Costa Rica, rather than on addressing their needs. Indigenous communities could play an important role in the humanitarian response, but they receive little to no government help. Migrant reception stations are inadequate, posing risks to migrants and asylum seekers. Limited state capacity, lack of access to drinking water and strained health facilities means people have their basic rights denied.

In a worrying step, on March 4, the Panamanian government suspended the work of Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF or Doctors without Borders) in the country, arguing that their agreement with the humanitarian group had ended in December. MSF, which played a leading role in assisting migrants and asylum seekers, including hundreds of victims of sexual violence, said it has repeatedly sought to renew the agreement.

Additionally, Panamanian security forces appear to have engaged in abuses against migrants and asylum seekers in some specific instances. Obstacles to reporting crimes and the absence of oversight mechanisms create an environment rife for impunity for security forces’ abuses, including sexual violence.

Crimes against migrants and asylum seekers in the Darién Gap, including pervasive cases of sexual violence, go largely uninvestigated and unpunished on both sides of the border. Accountability for these abuses is rare, due to a combination of limited resources and personnel, a lack of a criminal investigation strategy for these cases, and poor coordination between Colombian and Panamanian authorities.

Migrants and asylum seekers crossing the Darién Gap transit through communities that have experienced longstanding marginalization and neglect. In Colombia’s Urabá region, which has high poverty rates, limited state presence (other than the military) and ineffective action on organized crime has meant the Gulf Clan exerts control and abuses locals. Poverty rates are even higher and state abandonment more pronounced in Afro-Colombian and Indigenous communities. In Panama’s Darién province, the poorest in the country, people lack sufficient access to basic public services like water, sanitation and health care. Indigenous people, including in the communities of Bajo Chiquito and Canaán Membrillo, where migrants first arrive after crossing the Darién Gap, suffer high levels of poverty and poor access to public services. After decades of lack of opportunities and neglect, some communities on both sides of the border profit from the increase in migration.

Addressing the situation in the Darién Gap will require broader efforts from across the region. As Human Rights Watch has recommended in the first report in this series, Latin American governments and the United States should reverse measures that are preventing access to asylum and forcing people into dangerous crossings like the Darién Gap. They should honor the 40th anniversary of the 1984 Cartagena Declaration, a landmark international instrument on refugees’ rights in Latin America, to adopt rights-respecting policies.

In the meantime, Colombian and Panamanian authorities should do more to respect their international human rights obligations discussed in this report. They should ensure the economic and social rights of migrants and asylum seekers crossing their countries, as well as local communities, prevent abuses against by armed groups and bandits, and carry out meaningful efforts to investigate, prosecute, and punish abuses. Both Colombia and Panama should appoint a special advisor or senior official to coordinate the response to increased migration across the Darién Gap and bolster the cooperation among the two governments and with UN and other humanitarian agencies.

Both governments should work with humanitarian organizations and local communities to establish a joint mechanism to rescue people who go missing in the Darién Gap and to identify and recover dead bodies in the jungle. They should also strengthen efforts to prevent and investigate sexual violence against migrants and asylum seekers, including by increasing forensic capacity in the region, prioritizing investigations into these cases and addressing obstacles that make it harder for victims to report crimes. Working with humanitarian organizations, governments should bolster medical, including psychological, assistance for victims.

Whatever the reason for their journey, migrants and asylum seekers crossing the Darién Gap are entitled to basic safety and respect for their human rights along the way. Colombia and Panama can and should do more to protect their rights.

Key Recommendations

To the Colombian and Panamanian states:

- Appoint a special advisor or senior official to coordinate the response to increased migration across the Darién Gap and bolster the cooperation among the two governments and with UN and other humanitarian agencies.

- Improve conditions in departing municipalities and Indigenous communities both for local people and migrants and asylum seekers, especially by improving social investment to ensure access to electricity, drinking water, sewage system, trash disposal, latrines, and healthcare services.

- Work together and with humanitarian organizations and local communities to create a joint mechanism to rescue or recover and identify the bodies of people who go missing in the Darién Gap.

- Work together and with humanitarian organizations and local communities to create a joint mechanism to identify vulnerable migrants and asylum seekers, including unaccompanied children, pregnant people, or people with medical conditions, and ensure an appropriate response upon their arrival in Panama.

- Ensure that the two Attorney General’s Offices work together to develop a joint strategy to bolster reports of abuses occurring in the Darién Gap, identify patterns in cases committed against migrants and asylum seekers and seek the dismantling of criminal groups attacking and/or profiting on them.

- Work to implement a joint security strategy that ensures protection for migrant populations and local communities on both sides of the border.

- Ensure further humanitarian assistance in the area, including by supporting the work of humanitarian organizations, including MSF, and ensuring that they can operate without undue restrictions.

To the Colombian state:

- Enhance the presence and capacity of national and local institutions in the Urabá region, including of Migración Colombia, ICBF, the Attorney General’s Office, and the Ombudsperson’s Office.

- Support local municipalities by establishing a specific budget for them to respond to migrant and asylum seekers’ needs, and by working with them to ensure their development plans take into consideration the arrival and transit of migrants and asylum seekers and establish appropriate contingency and response plans.

- Ensure that prosecutors investigate the role of the Gulf Clan in taking migrants and asylum seekers across the Darién Gap, including by allocating prosecutors of the working group to investigate human trafficking, migrant smuggling, and related crimes in the Urabá region.

- Ensure that any future ceasefires or negotiations with the Gulf Clan include clear protocols and safeguards to prevent the group from expanding its territorial control and committing additional abuses.

- Work with humanitarian organizations to conduct periodic surveys on the number of migrants and asylum seekers in the Urabá region, identify their needs, and share this information with the Panamanian government on a regular basis.

To the Panamanian state:

- Work with UN and humanitarian NGOs to develop an inter-sectoral contingency plan to respond to the situation in the Darién and ensure assistance and protection to migrants, asylum seekers, and the local population, considering the needs of specific groups based on their ethnicity, origin, race, age, gender, disability, and sexual orientation.

- Modify the “controlled flow” strategy (also called “humanitarian flow strategy”) to establish a clearly articulated plan that considers the needs of migrants and asylum seekers and ensures their right to seek asylum and to be free from any arbitrary restriction on movement.

- Enhance institutional capabilities in the Darién region, particularly those of the Ombudsperson’s Office, ONPAR, SENNIAF, Ministry of Health, and Ministry of Women, including by ensuring an increase presence of female staff and of translators, and that these agencies are present in the Indigenous communities or reception stations.

- Increase the capacity of the boarding facility for children in Metetí and develop, disseminate, and implement written protocols for the identification and care of separated and unaccompanied children.

- Ensure full implementation of the 2022 agreement that allows judges and prosecutors to consider anticipated sworn testimony from migrants and asylum seekers to avoid the need for an in-person appearance at trial (the procedure known as “prueba anticipada”).

To the US Government and all international donors:

- Establish or expand safe, orderly, and regular pathways for migration and enhance the availability and flexibility of such pathways for people considering entering the Darién Gap.

- Seize the 40th anniversary of the 1984 Cartagena Declaration, a landmark international instrument on refugees’ rights in Latin America, to adopt rights-respecting policies, in particular, by implementing a region-wide temporary protection regime that would grant all Venezuelans and Haitians temporary legal status.

- Fund credible efforts to improve the humanitarian response in the Darién Gap, including to ensure dignified migration centers and other shelters; to increase humanitarian aid, improving the conditions in departing municipalities in Colombia and Indigenous communities in Panama; and to prevent and investigate abuses, including sexual violence, against migrants.

To the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and the International Organization for Migration (IOM):

- Establish an inter-agency coordination mechanism in Panama to respond to the challenges of increased migration, following the example of the GIFMM in Colombia and ensuring that the mechanism has the capacity to identify gaps in assistance and where available donor funds should be directed.

- Build on the experience of the Inter-Agency Coordination Platform for Refugees and Migrants from Venezuela (R4V) to ensure monitoring, documentation, and analysis of migration of people of all nationalities, including Haitians, Cubans, and Ecuadorians.

Methodology

This report is part of a series of Human Rights Watch reports on migration in the Americas and the Darién Gap. A previous report documented how a lack of safe and legal pathways has pushed migrants and asylum seekers fleeing human rights crises in Latin America to risk their lives crossing the Darién Gap.[1] A forthcoming report is expected to focus on the drivers of migration in the region—including the situations in Venezuela, Haiti, and Ecuador, as well as flaws in the integration and regularization policies of several South American countries through or from which migrants often travel.

In researching the situation in the Darién Gap for the series, Human Rights Watch visited the Colombian side of the Darién in April 2022 and June 2023 and the Panamanian side in May 2022 and March 2023. Furthermore, Human Rights Watch conducted phone interviews with sources in the area between January 2022 and March 2024. In total, researchers interviewed more than 160 migrants and asylum seekers who had or were about to cross the Darién Gap. Some people—including a few who had reached the United States, Costa Rica, or Mexico—were interviewed by phone. Interviews were conducted in Spanish, Portuguese, French, and English.

During its visits and by phone, Human Rights Watch also interviewed nearly 50 humanitarian workers from UN agencies and humanitarian organizations, as well as Colombian and Panamanian authorities within the national Ombudsperson’s Offices, Attorney General’s Offices, Ministries of Foreign Affairs, and migration offices, among others.

Human Rights Watch also interviewed by phone migration experts, as well as international, regional, and local organizations and legal clinics working with migrants and asylum seekers throughout the region, including in Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru.

Most migrants and asylum seekers and some humanitarian workers spoke to researchers on condition that we withhold their names and other identifying information. This report has also withheld interviewees’ details when Human Rights Watch assessed that publishing the information would put someone at risk. Human Rights Watch uses pseudonyms to identify migrants and asylum seekers interviewed during its research.

Human Rights Watch informed all participants of the purpose of the interview, its voluntary nature, and how the information would be used. Each participant orally consented to be interviewed. They did not receive any payment or other incentive. Where appropriate, Human Rights Watch provided migrants and asylum seekers with contact information for organizations offering healthcare, legal, social, or counseling services.

Human Rights Watch took care when interviewing survivors of abuses, particularly of sexual violence. When possible, Human Rights Watch received information from humanitarian workers supporting survivors to minimize the risk that recounting their experiences could further traumatize the survivors.

Human Rights Watch reviewed academic studies regarding migration in Latin America, as well as data and reports by the Colombian, Panamanian and US governments; UN agencies; international, regional, and local human rights and humanitarian organizations; local legal clinics; and media outlets.

Significantly, Human Rights Watch obtained access and analyzed anonymized data from 1,382 surveys of migrants and asylum seekers conducted by the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) in the Darién Gap between July 2022 and June 2023.[2]

As part of the research on migration in the Americas and the Darién Gap, Human Rights Watch sent multiple information requests to government authorities. The information requests included:

- In July 2022, July 2023 and February 2024, Human Rights Watch sent information requests to the following Colombian authorities regarding the departure of migrants and asylum seekers from Colombia and authorities’ response: the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Ministry of Defense, the Ministry of Interior, the national police, the national migration office (Migración Colombia), the Attorney General’s Office, the Ombudsperson’s Office, the Colombian Family Welfare Institute (Instituto Colombiano de Bienestar Familiar, ICBF), and the mayor’s offices of Necoclí, Turbo, Acandí, Juradó, and Unguía. In 2022 and 2023, Human Rights Watch received partial or complete responses from all Colombian authorities with the exception of the Mayor’s Office of Acandí and Migración Colombia. As of March 21, 2024, only the ICBF and the Mayor’s Office of Necoclí had responded to the February 2024 information requests.

- In July 2022, March 2023 and February 2024, Human Rights Watch sent information requests to the following Panamanian authorities regarding the arrival of migrants and asylum seekers to Panama and authorities’ response: the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Ministry of Public Safety, the Ministry of Health, the National Migration Service (Servicio Nacional de Migración, SNM), the National Border Service (Servicio Nacional de Fronteras, SENAFRONT), the Attorney General’s Office, the Ombudsperson’s Office, the National Service for Children, Adolescents, and Families (Secretaría Nacional de Niñez, Adolescencia y Familia, SENNIAF), and the National Office for Refugee Care (Oficina Nacional para la Atención de Refugiados, ONPAR). In 2022 and 2023, Human Rights Watch received partial or complete responses from all Panamanian authorities. As of March 21, 2024, only the Attorney General’s Office had responded to the February 2024 information requests.

I. Background: The Darién Gap

The Darién Gap is a swampy jungle that lies between the Colombian state of Chocó and the Panamanian province of Darién, forming a natural border not only between those countries, but also between South and Central America.

The terrain is steep and slippery, the rivers rushing, especially during the rainy season. Most routes follow paths that crest a rugged mountain range with ridges as high as 1,800 meters (6,000 feet)—where flags mark the Colombian-Panamanian border. People crossing call the highest pass “Death Hill” (Loma de la Muerte) and the Turquesa river “Death River” (Río de la Muerte), for the large number of dead bodies in its waters.[3] Temperatures range from 20 to 35 degrees Celsius (75 to 95 degrees Fahrenheit), with heavy rainfall and flooding from May to December.

For decades, migrants and asylum seekers migrating northward from South America have used the Darién Gap, generally with the intent of entering the US. Thousands of people, from more than 70 nationalities,[4] have made the journey through what the International Organization for Migration (IOM) calls “one of the most dangerous migration routes.”[5]

Despite a significant drop from in 2020, caused by border closures and quarantine measures adopted in response to the Covid-19 pandemic, the number of people crossing the Darién Gap soared by almost 4,000 percent between 2020 and 2022.[6] The number of people crossing has increased dramatically in recent years, reaching a record of over 500,000 crossings in 2023.[7] Panamanian authorities estimate that the number will reach around 800,000 crossings.[8]

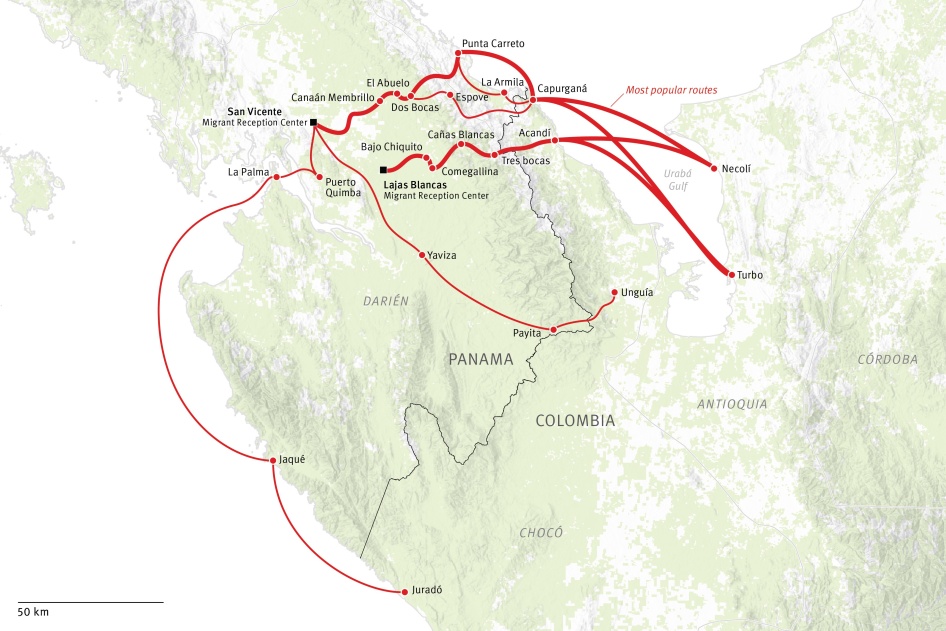

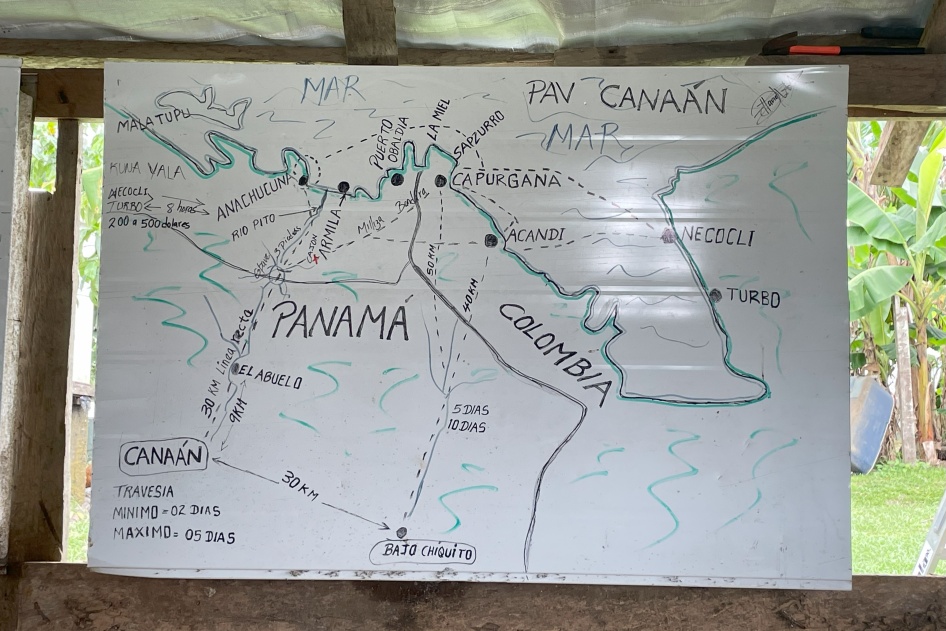

Transit routes through the Darién Gap have changed over the years in response to the needs of migrants and asylum seekers and restrictions imposed by Panamanian authorities as well as by the Gulf Clan.[9]

Migrants and asylum seekers start their journey across the Darién Gap by boat in Necoclí or Turbo, in Colombia. After staying for a couple of hours or overnight in shelters in Acandí or Capurganá, migrants and asylum seekers start their days-long journey through the jungle, sleeping in their tents or outdoors along the way. Interviewees describe climbing steep hills until reaching the summit where a flag marks the border with Panama.

Once they cross the border, migrants and asylum seekers descend along the river, passing by Indigenous settlements and then hiring Indigenous people to transport them in small wooden canoes, known as “piraguas,” to the Indigenous communities and then to the Migrant Reception Station (Estación de Recepción Migratoria, ERM).[10]

During their journey, migrants and asylum seekers of all nationalities frequently experience robbery and serious abuses, including sexual violence.

Over 30 percent of the roughly 1,380 people interviewed by UNHCR in the Darién Gap between July 2022 and June 2023 reported suffering some type of abuse in the jungle, including theft (20 percent), fraud (14 percent), and threats or other acts of “intimidation” (11.3 percent).[11]

MSF assisted 328 people who reported sexual violence while crossing the Darién between April and December 2021;[12] 232 in 2022; and 676 in 2023, including 214 only in December.[13] In January 2024 MSF recorded 120 more cases.[14] MSF considers the total number of survivors to be likely higher.[15]

Victims, humanitarian workers, and Panamanian authorities told Human Rights Watch that in most cases of sexual violence, armed men ambushed groups of migrants and asylum seekers, separated them by gender, and forced the women to take off their clothes. Women said that the men sexually assaulted them, often under the pretext of searching for hidden money, and in some cases raped them.[16]

Many migrants have lost their lives or gone missing trying to cross the Darién Gap. The IOM’s Missing Migrants Project reported that at least 245 people had disappeared in the Darién between 2021 and March 2024.[17] It also said that “anecdotal reports” suggested that figure represented “only a small fraction of the true number of lives lost.”[18] In September 2023, the head of Panama’s National Migration Service, Samira Gozaine, told the press that “we will never know” the number of people who died or went missing in the jungle.[19]

II. Colombia’s Response

The government of Colombia lacks a clear strategy to ensure the rights of migrants and asylum seekers crossing the Darién Gap.

The lack of an adequate response and the poor government presence in the area have put the rights, including to life, physical integrity, health, water, and food, of people at risk and created a breeding ground for the Gulf Clan and actors linked to it to control of people’s movement as well as the profit that is made from migrants and asylum seekers’ desperation and vulnerability.

Humanitarian Response

By the time migrants and asylum seekers arrive to Necoclí or Turbo to start their journey across the Darién Gap, they have walked or traveled for days.[20] Many told Human Rights Watch that they crossed entire countries facing extortion, abusive migration authorities, and discrimination, and that they had to sleep and ask for money in the streets to continue their journey.[21]

The main need on the Colombian side of the Darién Gap is food, according to the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) and the Interagency Group for Mixed Migration Flows (Grupo Interagencial de Flujos Migratorios Mixtos, GIFMM), a coordination platform for humanitarian actors and government agencies. Other needs included potable water, shelter, child protection, and health services.[22]

Since late 2022, the GIFMM, co-led by UNHCR and IOM, has been coordinating the efforts of humanitarian organizations and local authorities, leading to some improvements in the overall humanitarian response.[23] Additionally, in 2023, Colombian authorities increased their presence in the Gap, deploying personnel from Migración Colombia, the state agency handling migratory issues, and the ICBF, charged with child protection.[24]

In 2023, the Ministry of Equality and Equity established a Directorate for Migrant Population to oversee migration matters. Its goal is to implement policies that safeguard the rights of migrants, including those in transit, and to coordinate immediate humanitarian aid and socio-economic integration.[25] The ministry is currently developing a protocol and a policy to assist migrants. The ministry told Human Rights Watch that they plan to open centers to assist migrants and asylum seekers in Necoclí, Turbo, Acandí and Capurganá.[26]

Despite these efforts, Human Rights Watch found serious shortcomings that put migrants and asylum seekers at risk. Among them, authorities have no reliable estimate of the number of migrants and asylum seekers in the area or those crossing to Panama, or of their humanitarian needs.[27]

In June 2023, Migración Colombia introduced the Safe Transit app (Tránsito Seguro), allowing foreign individuals with irregular status in Colombia to stay in the country and use buses or other forms of transportation for up to 10 days without facing penalties.[28] Officers from Migración Colombia told Human Rights Watch that they assume migrants have left after the 10-day period but make no attempt to verify or register their departure.[29]

Departing Municipalities

Communities living in municipalities on the Colombian side of the Darién region also face chronic rights abuses stemming from limited and ineffective social institutions and services, the effects of a long-standing armed conflict, drug trafficking and high levels of multidimensional poverty.[30]

Rates of multidimensional poverty, which reflects income as well as the availability of and access to rights-essential goods and services like education, adequate housing, and drinking water, are very high in these municipalities compared to other areas in the country.[31] According to government statistics, the percentage of people who fall below Colombia’s nationally defined minimum of multidimensional poverty in Necoclí (57.63 percent), Turbo (39.15 percent), Acandí (36.44 percent), Juradó (56.11 percent), and Unguía (48.59 percent), are between two and four times higher than the national average (14.28 percent), with percentages going up to over 70 percent in some rural areas.[32] In both Chocó and Antioquia states, Indigenous and Afro-Colombian households are much more likely to experience monetary poverty because of low incomes.[33]

In April 2023, Colombia’s and Panama’s Ombudsperson’s Offices found that municipal budgets and development plans on the Colombian side failed to take into consideration “the phenomenon of migration as well as the demand for services it entails.”[34] The mayors’ offices lack the necessary expertise, personnel, and financial resources to adequately respond to the influx of migrants and asylum seekers, Colombian officials and humanitarian workers told Human Rights Watch.[35]

The influx of migrants and asylum seekers has transformed local economies, affecting the cost of living for both local communities and those passing through.[36] The high price of goods and services such as transportation, food, accommodation, and hygiene items, increases the need for humanitarian aid, according to humanitarian organizations. Many migrants and asylum seekers are unable to obtain enough money to pay for boat tickets and other fees charged by boat companies to continue their journey and are forced to stay for several days or weeks in the Colombian side of Darién, where they are exposed to violence and abuse.[37]

The absence of shelters in Necoclí and Turbo drives many migrants and asylum seekers—particularly Venezuelans—to sleep in tents at the beaches, where the risk of violence is higher.[38] In 2016, 2,000 Cuban migrants and asylum seekers were stranded in Turbo due to heightened controls and restrictions in Central American countries. In 2021, Necoclí experienced a similar situation, as tens of thousands of mainly Haitians were stranded due to Covid-19-related restrictions and overcrowding in Panama’s ERMs. While local authorities said that some 20,000 people were stranded, humanitarian actors estimated the number could be as high as 35,000. In both situations, migrants and asylum seekers were forced to improvise shelters, including tents by the beach, where they were exposed to the natural elements and had significant unmet humanitarian needs.[39]

The GIFMM noticed periodic increases of migrants and asylum seekers sleeping in the streets and beaches in 2023.[40] In early 2024, the GIFMM reported that each night roughly 300-350 people were sleeping in the beaches in Necoclí and 150-200 in Turbo.[41]

In February 2024, following the arrest of two boat captains accused of “human smuggling,” boat companies in Necoclí suspended their services for five days in protest. Necoclí and Turbo witnessed a significant increase in the number of stranded migrants, which surpassed the 3,000; around 600 were sleeping at the beach in Necoclí and 300, in Turbo, according to the Colombian Ombudsperson’s Office, the Mayor’s Office of Necoclí and humanitarian organizations.[42]

People who sleep on the beach lack access to adequate housing and to goods and services essential to their rights, and they are at higher risk of being abused by the Gulf Clan and others, including through sexual and labor exploitation.[43] The Clan has forced some of them to carry drugs in small amounts across the Gap.[44] “Once in Acandí, we got to a camp controlled by the drug trafficking group Gulf Clan,” a woman told Human Rights Watch. “I did not have to pay [to cross the Gap], but some men asked me to carry a package. They said it contained drugs and if the package did not arrive, they would take my kids. After two days walking in the jungle, a group intercepted us and took the packages away, then they let us continue.”[45]

Local authorities, especially in Necoclí, do not allow migrants and asylum seekers to keep their tents on the beach by day. Every morning, police officers require them to clear the beach.[46] “In the mornings they come and ask us to put all our things away,” said a Venezuela woman pointing to some backpacks underneath a palm tree.[47] “They are making us take away our tents at 6 a.m., and I have to wake up my children. The 14 and 16-year-old children work selling sweets [on the streets], but there’s a lot of competition now,” said another Venezuelan woman who had already spent three months in a beach in Necoclí, gathering money to cross the Darién Gap.[48]

Necoclí

Necoclí, with a population of roughly 45,000 people, is a coastal town near the Caribbean Sea.[49] Currently, it is the main departure point for migrants and asylum seekers attempting to cross the Darién Gap, with boats departing to Acandí and Capurganá. According to the GIFMM, 91 percent of the people that crossed the Darién in 2023 departed from the docks in Necoclí and Turbo.[50]

From January 2023 to February 2024, over 408,000 departed from Necoclí to cross the Gap, according to data from maritime transport companies.[51] The GIFMM estimates an average of 1,000—1,200 departures daily, reaching peaks of over 3,000 in certain periods of the year.[52]

The Risk Management department of the Mayor’s Office leads the response to migration issues, as well as any other “emergency situations.”[53] In 2023, the Mayor’s Office created a working group (known in Spanish as “Mesa de Gestión Migratoria”) with humanitarian organizations and national government agencies. The decree establishing the working group provides that it should meet at least every three months to discuss and develop local public policies related to migrants and asylum seekers.[54]

Since January 2024, the new municipal administration has conducted two meetings of the working group and, according to staff of the Mayor’s Office, the members are working to establish an “action plan,” which would include the establishment of a transitory housing facility.[55]

Migrants and asylum seekers who have enough money to pay for housing in hotels or private rooms, food, and other services are seen as a source of income for the municipality. “The migrant with money is well-received in Necoclí as an economic catalyst,” said an official of the Ombudsperson’s Office. “The migrant who does not have money is not useful and is left unattended.”[56]

The humanitarian response in Necoclí is primarily carried out by humanitarian organizations through the coordination of GIFMM. “The Colombian government left the response in the hands of [international] cooperation,” a humanitarian worker said. “There is no interest from the national government in addressing the issue.”[57]

Private nonprofit humanitarian organizations and UN agencies have largely filled the gap created by the absence of accessible public services for migrants and asylum seekers in town, including by distributing hygiene items and water purification tablets, providing information about routes of travel, and providing food and health services.[58] For example, GIFMM-affiliated agencies can send migrants to the local hospital, which is treating migrants and asylum seekers.[59] Since the first level of medical attention is covered by the municipality, local authorities told Human Rights Watch that the municipality owes 135 million Colombian pesos (around US$35,000) to the hospital, though the figure was much higher in 2023 and local authorities fear it may increase again.[60] According to the GIFMM, since 2022, IOM is paying for health care for the cases of migrants and asylum seekers that it refers to the hospital, particularly for pre-natal checkups.[61]

In August 2023, GIFMM said that the humanitarian services were struggling to adequately respond to the large number of people sleeping on the beaches and streets of Necoclí, who, as described above, are exposed to various risks.[62]

|

Jacinto Molina (pseudonym), 28, departed Venezuela in 2022 with his 22-year-old wife and their 4-year-old son after he lost his job as a truck driver.[63] Facing financial hardship, they struggled to afford food. Jacinto and his family had slept in a tent on the beach in Necoclí for two days when he spoke with Human Rights Watch. Jacinto said that no one from the Mayor’s Office had contacted them to assist. They received water and food from humanitarian organizations. To gather enough money for the boat fare, Jacinto and his wife started collecting garbage and recycling, earning 10,000 pesos (approximately US$2.50) each day. They were hoping to obtain $40 each to pay for their boat ticket. Alicia Olmos (pseudonym), a 22-year-old Venezuelan coming from Ecuador, traveled two months before arriving at Necoclí.[64] Alicia, her husband—who became sick in Necoclí—and her children had to sleep for seven days on the beach before being able to buy the boat tickets. Alicia asked for money on the streets; some Haitian migrants gave her $50. She said she was afraid to ask for help from Colombian authorities because she feared they would take her children because they were sleeping on the streets. “We need to keep going, no matter what, and at any cost. We have no other options; we have been homeless; we have survived by begging for too long. It’s not fair,” Alicia said. “We left Venezuela fleeing poverty, and we have to reach the United States because it’s the only place where we might have a chance to move forward.” Luis López (pseudonym), a young Venezuelan man, had travelled from Peru with his pregnant wife for over a week and a half, when Human Rights Watch interviewed him.[65] He pointed to discrimination against Venezuelans and criminality in Peru. He had worked for two days carrying bags of sand, with a total pay of 50,000 pesos (around $12). Luis was trying to earn money to continue the journey through the Darién. |

In April 2023, the GIFMM, the Mayor’s Office, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and UN agencies began discussions to open a so-called “Border Assistance Center” (Centro de atención fronterizo, CAF) that would concentrate all the services provided by humanitarian organizations and the Colombian government.[66] In June, humanitarian organizations and the ICBF expressed concerns about the location of the CAF. The Mayor’s Office wanted to locate it on a property a 20-to-30-minute walk from the beaches where migrants and asylum seekers sleep or the docks from where they depart. They feared such location would hinder access for many migrants and asylum seekers.[67] As of March 2024, the CAF had not been built.[68] The Ministry of Equality officials said their ministry will build centers to assist migrants instead.[69]

In July 2023, Colombia’s Ombudsperson’s Office established a “House of Rights” (Casa de Derechos), a space to provide advice and support to displaced, asylum seekers, and migrant populations.[70]

Turbo

Turbo, with 133,430 inhabitants, is located south of Necoclí.[71] After nearly 2,000 migrants and asylum seekers, most from Cuba, were stranded in Turbo in 2016, fewer people have departed from there. However, since late 2022 there has been an increase, particularly of migrants and asylum seekers with fewer financial resources.[72] The GIFMM and the Mayor’s Office estimated that around 1,000 people were departing each day from Turbo by late August 2023, although the number decreased by December, following a seasonal reduction in the number of people crossing the gap.[73]

The increase in departures from Turbo means that humanitarian organizations have to divide their resources between Necoclí and Turbo. Many still do not have permanent staff in the area and move between Turbo and Necoclí to carry out their work.[74] While some humanitarian organizations assist and provide relevant information to migrants and asylum seekers in Turbo’s boat dock, the GIFMM noted in August 2023 that the “response is limited” and “resources available are scarce.” Mobilization of humanitarian workers “involves a logistical and financial effort beyond the current capacity,” the GIFMM said.[75]

“Turbo has a [migrant and asylum seeker] population with less information and increased vulnerabilities,” said a member of a humanitarian organization itinerantly operating in the municipality.[76] In August, GIFMM estimated that at the moment 400 people needed food and that 12,000 liters of water and eight latrines were required to cover water and sanitation needs.[77]

The Mayor’s Office told Human Rights Watch in 2023 that it did not have a “contingency plan” to respond to migration in their municipality, nor a “budget for humanitarian assistance of migrants.”[78] Due to the absence of a shelter and the limited “hotel capacity […] public places […] have become shelters for overnight camping,” the office said.[79]

In February 2024, the Mayor’s Office of Turbo established a working group, similar to that of Necoclí. It also “proposed” setting up a temporary accommodation space for migrants and asylum seekers near the bus terminal.[80]

Acandí

Acandí, with some 15,000 inhabitants, is located near the Caribbean Sea and the border with Panama.[81] It is the last Colombian municipality many migrants and asylum seekers reach before entering the jungle.

In February 2023, the Inspector General’s Office reported that the municipality did not have a health center with capacity to aid migrants needing urgent healthcare. It also highlighted the absence of government institutions, including Migración Colombia.[82]

In Acandí and Capurganá, a small town in the same municipality, there are shelters for migrants and asylum seekers run by non-state actors.[83] They are highly organized, the Colombian Ombudsperson’s Office said, with many local people involved in their operation,[84] and offer several services, including a place to sleep or to prepare their meals.[85] Some migrants and asylum seekers told Human Rights Watch that they saw armed men in the camps, who ensured order and the safety of people, including by preventing robberies.[86] Several sources said they believed the men are linked to the Gulf Clan.[87]

As of March 2024, only humanitarian organizations providing health services were operating inside the shelters, including the Colombian Red Cross, the NGO Action Against Hunger and Médecins du Monde.[88] Other humanitarian organizations told Human Rights Watch they do not have a permanent presence in Acandí or Capurganá, mainly because of security reasons. The lack of state presence in these camps could put their workers at risk or legitimize private actors that control the shelters, they said.[89]

The lack of permanent presence of Colombian authorities and humanitarian organizations inside the shelters means that authorities are unable to monitor, prevent or respond to abuses against migrants and asylum seekers.[90] “There have been reports about survival sex, ‘hormigueo’ [the use of migrants and asylum seekers to move drugs across the border], some intimidation by armed individuals within the shelters, among others, but we have not been able to verify [these reports],” a humanitarian worker said.[91]

In August, the Ombudsperson’s Office said they were hoping to establish a “house of rights” in Acandí but lacked sufficient funding.[92]

On February 5, 2024, the Mayor’s Office of Acandí established a working group with the purpose of coordinating “actions related with the promotion, protection, access to rights, assistance and socio-economic integration” of migrants and asylum seekers.[93] As of early March, the group had yet to meet.[94]

Unguía and Juradó

Unguía and Juradó are two municipalities in the Chocó state, with roughly 14,000 and 7,000 inhabitants, respectively.[95] Migrants and asylum seekers use the routes crossing through these municipalities less often than the others described above.[96]

Unguía has a low presence of state institutions such as Migración Colombia, and the areas of the municipality with the highest passage of migrants and asylum seekers have extensive coca crops.[97] The Ombudsperson’s Office said that if the number of people using this route increases, “Unguía would not be capable of handling [it].”[98]

In August 2022, the Mayor’s Office of Juradó told Human Rights Watch that they only knew about 12 people who had transited through the municipality. The municipality is mostly composed of islands and jungle and the office said they did not have the capacity to identify people transiting through areas other than the main city. They only learned about them when “regrettable events” took place, the office said, citing as an example a December 2021 shipwreck in which at least six people died.[99]

The office said that they “do not have sufficient resources”—both financial and staff—to respond to any influx of migrants and asylum seekers and lack protocols to coordinate the response with other municipalities in Colombia, like Necoclí and Acandí, or with Panamanian authorities.[100]

As of March 2024, Unguía and Juradó lack permanent presence of humanitarian organizations and of national government institutions such as ICBF and Migración Colombia.[101] In 2021, UNHCR helped the Governor’s Office of Chocó to establish a “contingency plan” for the mayor’s offices of Juradó and neighboring Bahía Solano and Nuquí to respond to migration in their municipalities. But humanitarian workers told Human Rights Watch in August 2023 that the plan had not been implemented.[102]

Protection, Security, and Access to Justice

Limited State Presence and Security Operations

Municipalities on the Colombian side of the Darién Gap, including Acandí, Unguía, Juradó, Turbo, and Necoclí, have “historically suffered from state abandonment,” according to Colombia’s Ombudsperson’s Office.[103] Most of them are “category six,” the lowest in a nationwide government measurement that considers the number of inhabitants, the municipalities’ income, and its institutional capacities.[104] Their residents suffer from a limited availability of roads and infrastructure, inadequate health care and education, low coverage of basic services, and limited presence of law enforcement agencies.[105]

Necoclí, Turbo, Acandí, and Unguía, have been included in the so-called Development Programs with a Territorial Focus (Programas de Desarrollo con Enfoque Territorial, PDET), a plan created in the 2016 peace accord with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia, FARC) guerrillas which seeks to increase the presence of state institutions in areas highly affected by the armed conflict, poverty, and illegal economies.[106]

However, efforts to implement the PDET in these municipalities have been limited.[107] As of January 2024, authorities had finalized only a handful of public works established under the PDET[108] in these municipalities and less than half of the PDET “initiatives” were under implementation.[109]

The mayor’s offices have limited capacity, and the Gulf Clan exercises control over large parts of the territory, engages in illegal economies, including drug trafficking, and commits serious abuses.[110]

Through security operations Agamenón, which started in 2015, and Condor, which began in late 2021, Colombian authorities have sought to dismantle the Gulf Clan at a national level. These operations captured high-ranking leaders of the Clan, including Dairo Antonio Úsuga, alias “Otoniel,”[111] but failed to significantly weaken the group’s control.[112] In recent years, the Clan has expanded its presence across Colombia; its members were present in 392 municipalities in 2023,[113] compared to 253 in 2022[114] and 213 in 2019, according to the Ombudsperson’s Office.[115]

Since President Gustavo Petro took office in August 2022, his government has sought a negotiated demobilization of the Gulf Clan. After four months of “exploratory meetings,” on December 31, 2022, President Petro announced a six-month bilateral ceasefire with the Clan,[116] as well as with four other armed groups. The ceasefires covered abuses by armed groups against civilians and fighting between the Colombian armed forces and police and each armed group, but not fighting among the armed groups.[117]

There appeared to be insufficient preparation, including of relevant protocols, for the ceasefires, resulting in significant obstacles to their continued observance. Among them, the Attorney General’s Office questioned the legal basis to suspend arrest warrants against members of the Clan, as established under the ceasefire, and refused to do so.[118] The Gulf Clan violated the ceasefire on multiple occasions and investigators from the Special Jurisdiction for Peace (Jurisdicción Especial para la Paz, JEP), a transitional justice court system, found that the ceasefire had “no impact” on the armed group’s behavior toward civilians.[119]

The Gulf Clan also continued its efforts to expand its presence across the country, including by fighting with the National Liberation Army (Ejército de Liberación Nacional, ELN) and dissident groups that emerged from the demobilized FARC guerrillas.[120] The government ended the ceasefire with the Gulf Clan in mid-March 2023—three months before the deadline—arguing that the armed group had repeatedly attacked the police.[121]

Since then, security forces have restarted operations against the Clan, including in Urabá, to arrest its members and dismantle cocaine laboratories.[122] As of mid-August, the Ministry of Defense said security forces had arrested 409 members of the Gulf Clan since January, including some in the Urabá region.[123] In late August, the Ministry of Defense told Human Rights Watch that they had launched a new police-led strategy to investigate criminal groups, including the Gulf Clan, linked to human trafficking.[124]

Additionally, in August 2023, the Ministry of Defense of Colombia and Panama’s Ministry of Public Safety signed an annual “operative plan” to “design coordinated actions” to fight organized crime.[125]

In March 2024, President Petro proposed a new negotiation with the Gulf Clan to “end their illicit businesses.” The Clan accepted.[126]

Investigations and Justice

Most of the abuses in the Darién Gap, including robberies and sexual violence, occur in Panamanian territory.[127]However, the efforts by Colombian justice authorities to investigate crimes such as killings, sexual violence, and extortion, that occur in their territory have been very limited and initiatives to dismantle the Gulf Clan in the region have produced few results.

As Human Rights Watch has shown, the Gulf Clan regulates the routes that migrants and asylum seekers can use, decides who can assist them on the way, extorts people who benefit from the movement of migrants, and establishes rules of conduct for locals and migrants alike, at times enforcing these rules through violence.[128]

Elsewhere in the country, the Attorney General’s Office has several strategies, known as “investigative projects,” to investigate and dismantle criminal organizations by investigating and prosecuting their leaders.[129] But because rates of homicides and other abuses are lower in the Colombian side of the Darién than in other parts of Colombia,[130] none of these projects focused on this area as of August 2023.[131]

Human Rights Watch interviews in Darién suggest that the lower level of abuses is linked to the Clan’s undisputed control over large parts of these territories and appears to be an intentional measure precisely to prevent the attention of law enforcement.[132] Additionally, the Clan ensures the low visibility of its operations in the region by hiring locals, who are not heavily armed but who extort people and ensure control, including of migrants and asylum seekers.[133]

In March 2022, the Attorney General’s Office announced a strategy to handle criminal cases related to human trafficking and migrant smuggling at a national and transnational level.[134] The strategy seeks to identify criminal structures and money laundering behind such crimes.[135]The Attorney General’s Office created a working group to investigate human trafficking, migrant smuggling, and related crimes. The working group had 14 prosecutors, but as of August 2023 only 11 had been assigned cases of human trafficking and migrant smuggling. These include seven located in Bogotá, one in Cali, one in Medellín, and two in Bucaramanga. Of the 11, only 4 prosecutors are exclusively dedicated to migrant smuggling and human trafficking investigations; the rest also conduct investigations into other human rights violations.[136]

The Attorney General’s Office told Human Rights Watch it had “dismantled” six criminal organizations dedicated to migrant smuggling through the Darién to Panama or from the San Andrés Island to Nicaragua by August 2023.[137] “These organizations engaged in fraudulent activities targeting US consular agents in visa acquisition as part of their modus operandi,” the office said.[138] The Ministry of Defense said that security forces have detained 52 people involved with migrant trafficking between January 2021 and August 2023 in the Urabá region, including Necoclí, Turbo, Apartadó and Acandí.[139]

In August 2023, the Attorney General’s Office told Human Rights Watch it had opened investigations into 494 cases of migrant trafficking allegedly occurring between January 2021 and August 2023. Of these, eight were connected to events in Necoclí, eight others to events in Turbo; five, in Acandí; and one, in Unguía. Most of the cases, 286, were in a preliminary stage; 46 were under formal investigation; 154 had reached a trial stage; and prosecutors had achieved eight convictions.[140] The office said that no victims of “migrant trafficking” had been rescued.[141]

Prosecutors do not appear to be conducting dedicated efforts to investigate the Clan’s illicit money flows arising from its control of migration across the Darién Gap. On the one hand, prosecutors focused on investigations of organized crime said that they are not investigating the Clan’s involvement in the movement of migrants.[142] On the other hand, prosecutors working on trafficking cases are not investigating the Gulf Clan.[143]

In December 2023, the Deputy Attorney General passed a resolution ordering prosecutors to establish a “strategy” to investigate the illicit money flows connected to migrant smuggling in the Darién Gap.[144] Under the resolution, the strategy should ensure coordination of several units within the Attorney General’s Office, including the trafficking working group and the organized crime, illicit finances and citizen security units, and seek the “strategic persecution” of assets, including through forfeiture.[145]

Additionally, prosecutors struggle to identify abuses committed against migrants and asylum seekers on the Colombian side of the Gap.[146] While the number of abuses occurring on the Colombian side is lower than on the Panamanian one, Human Rights Watch research suggests that some such cases occur on the Colombian side.[147] However, prosecutors in Apartadó and Necoclí told Human Rights Watch in 2022 that they had not received complaints about killings, sexual violence, or threats against migrants and asylum seekers, and the Attorney General’s Office said it does not keep a specific register of such cases.[148] One reason for the lower number of abuses occurring on the Colombian side appears to be that the Gulf Clan, which controls large parts of the area, has established prohibitions against harming migrants and locals in an apparent effort to avoid drawing the attention of law enforcement.[149]

Additionally, prosecutors and investigators do not appear to conduct proactive efforts to identify cases of abuses occurring in the beaches in Necoclí or Turbo or in the shelters in Acandí and Capurganá.[150]

One of the main obstacles faced by prosecutors in the Urabá is the lack of capacity. The Attorney General’s Office only has one prosecutor focused on organized crime in the Urabá region. He is in Apartadó.[151] However, other investigations against the Gulf Clan are carried out by prosecutors in Medellín.[152] In most departing municipalities, there is only one prosecutor; Acandí has two; Turbo, three.[153] In Urabá, the Technical Investigation Unit (Cuerpo Técnico de Investigación, CTI), the branch of the Attorney General’s Office charged with providing investigative and forensic support to prosecutors in criminal cases, is only permanently present in Apartadó.[154]

Because migrants and asylum seekers are seeking to cross the border, they often have little capacity or willingness to report abuses, and the authorities often have little interest in investigating.[155] Often, people do not report the crimes and, even when they do, their prompt departure from the country means the cases are unlikely to be prioritized.[156] This challenge could be addressed with increased cooperation with Panamanian authorities. The two Attorney Generals’ offices signed memoranda of understanding between 2017 and 2019.[157] Yet nobody appears to have been arrested based on such cooperation.[158]

Protection and Assistance to People at Higher Risk

Certain groups face an increased risk and vulnerability that adds to the already dire situation they face as migrants and asylum seekers. The response should take into consideration the specific needs of marginalized groups or people at higher risk. Despite some recent efforts, particularly regarding children, Colombia is not providing people adequate protection or assistance.

Children

As with other migrants and asylum seekers, Colombian authorities do not have an accurate estimate of the number of children who cross the Darién gap. This hinders the government’s capacity to identify and assist children, making them vulnerable, among other things, to human trafficking for sexual and labor exploitation.[159]

Colombia’s specific protocols to assist children at risk require the ICBF or family commissioners—municipal agencies charged with protecting women and children—to register children, including unaccompanied children, verify the status of their rights and adopt appropriate measures to protect them.[160] The Rights Restoration Administrative Process (Proceso Administrativo de Restablecimiento de Derechos, PARD), includes a specific roadmap for unaccompanied and separated children. According to the ICBF, since July 2023, 26 unaccompanied children aged 6 to 17 were included in this process in Necoclí, Turbo and Acandí.[161] Yet many such children are not identified, humanitarian workers said, meaning that the protocol is never applied to them. In addition to providing children with humanitarian aid, identifying children would allow Colombian authorities to notify their counterparts in Panama of their arrival, humanitarian workers said.[162]

In late 2021, the ICBF bolstered its presence in Necoclí by deploying a Comprehensive Protection Mobile Team (Equipo Móvil de Protección Integral, EMPI), to identify and assist children in need.[163] The team included a psychologist, a social worker, and a teacher.[164]

Additionally, since June 2023, the ICBF and UNICEF created a strategy to identify protection risks associated with migration through two Migrant Response Teams (Equipos de Respuesta a Migrantes, ERAM) in Necoclí, Turbo and Acandí.[165] The teams identify children who need protection, activate relevant protocols and protection programs, and articulate health, food and educational response.[166] According to the ICBF, as of January 2024, ERAM teams have provided care for over 3,000 children aged 0 to 17 in Necoclí, Turbo and Acandí.[167] These included children who were unaccompanied, stateless, separated, or otherwise in need of protection.[168] However, in August 2023 its staff said they were being “observed [and] followed” by unknown people.[169]

The ERAM teams report cases to the local family commissioner.[170] However, ICBF officials and humanitarian workers said that the family commissioner in Necoclí is often too slow to activate the relevant protocols to assist and protect the children and many just move on with their journey with no protection.[171]

Necoclí’s family commissioner told Human Rights Watch that her office lacked the “capacity” to respond to all cases, in part, because she only had three staff members, who also had to handle other cases in the municipality, such as of domestic violence.[172] One of the problems identified by both the commissioner and the ICBF is the lack of a shelter or boarding home for children at risk.[173] The closest facility to Necoclí is in Medellin, almost 400 kilometers away, said the commissioner. She has to personally accompany children to other cities in Colombia when an alternative care option, for example, a close family member, is identified. In June 2023, she said she had accompanied five children to Medellín, Bogotá, or Cartagena.[174]

Since December 2023, there is a Local Office (Unidad Local) of the family defender—a local dependent of the ICBF that guarantees the rights of the family in situations of conflict or risk—in the municipality of Necoclí, allowing “a faster response in cases where relevant protocols to protect children must be activated,” according to the ICBF. This Local Office also has a social worker, a psychologist, and a nutritionist.[175]

To ensure that children are not stranded at beaches all day, the ICBF has made available 50 spots in two daycare centers in Necoclí that take care of migrant and asylum seekers’ children under the age of five.[176] At the centers, children can bathe, eat, and play.[177] However, few migrant and asylum seekers’ children use the centers, in part because their parents fear that authorities might take their children away, alleging neglect.[178]

UNICEF and other partner organizations also provide safe spaces for children to play and receive some humanitarian aid.[179]

In February 2023, the Intersectoral Commission to Combat Migrant Smuggling—an inter-agency government commission created in 2016 to coordinate actions against migrant smuggling[180]—approved a “roadmap” that includes steps to assist children and adolescents whose rights are “threatened or have been violated in connection with migrant smuggling.”[181] At the time of writing, the ICBF was sharing the roadmap’s content with local authorities.[182]

Humanitarian workers and the Ombudsperson’s Office also expressed concern for local children who they say are dropping out of school to work in activities related to migration, including selling food or other goods necessary for the migrants’ journey.[183]

Women and Girls

Women and girls who sleep on the beaches are particularly exposed to sexual assault, exploitation and violence, humanitarian workers said.[184] “It feels unsafe as a woman to sleep in the middle of all those tents by the beach,” a Venezuelan woman told Human Rights Watch. “You hear noises at night and the only thing you can do is hope nobody will come into [your tent]. But the fear does not end here, then you have to cross the jungle.”[185]

Colombian authorities do not track the number nor gather information on women and girls on its side of the Darién, meaning that they lack a reliable assessment of their needs.[186]

Given the risks women and girls face in Colombia and the possibility of being sexually abused as they cross the border through the Darién Gap, members of Cooperative for Assistance and Relief Everywhere (CARE), a humanitarian organization, provide workshops by the beach in Necoclí to tell women and girls how to protect themselves in case of sexual assault. CARE gives them “sexual violence prevention kits” with, among other items, a plastic funnel for urination, a waterproof changing tent to prevent body exposure during the journey, menstrual panties, emergency contraception pills, and a whistle to alert others in case of an emergency or assault.[187]

The GIFMM also identified pregnant and lactating women sleeping on the ground at the beach in an area that, as described above, has water and sanitation problems.[188] Inadequate sanitation facilities and access to clean water heighten the risk of infections and complications during pregnancy and childbirth. The short periods of transit through some municipalities and lack of information about accessing health care often complicate prenatal check-ups.[189]

Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) People

UN experts have said that displaced individuals who identify as LGBT and gender diverse are more vulnerable to abuse than other migrants.[190] However, on the Colombian side of the Darién Gap border, these individuals often go unnoticed and do not receive assistance that responds to their needs, humanitarian workers said.[191]

Humanitarian workers make efforts to identify LGBT individuals who are sleeping on the beaches in Necoclí and Turbo. Even so, identifying them and their specific needs can be a challenge because many do not spend extended periods in these towns. Most of the information on migrant numbers available to humanitarian actors and Colombian authorities is initially obtained by boat companies. These companies do not ask about sexual orientation or gender identity, and many migrants and asylum seekers would opt not to disclose such information for fear of facing discrimination.[192]

MSF has documented cases of transgender people who make the journey dressed according to their sex assigned at birth to avoid discrimination.[193] Members of a humanitarian organization told Human Rights Watch that they relocated some transgender individuals from the beaches in Necoclí and Turbo to other cities in Colombia to ensure their safety from violence and discrimination.[194] Other LGBT people have used “humanitarian transportation” offered by UN agencies after deciding not to continue with their journey,[195] though it is unclear if their decision had to do with the difficulty of the trip, discrimination based on their sexual orientation or gender identity, or both.

III. Panama’s Response

Panamanian authorities enforce what they call a “humanitarian flow” (earlier labeled simply “controlled flow”) of migrants and asylum seekers through the country.[196] The strategy has a limited humanitarian component and grants few opportunities for people to seek asylum. It appears focused on channeling and restricting migrants’ and asylum seekers’ movement through Panama and ensuring that they cross to Costa Rica promptly, rather than responding to their immediate needs or providing them opportunities to file asylum applications in Panama.[197]

The strategy is led by the Ministry of Public Safety, which is charged with maintaining and defending Panamanian sovereignty and public order, and its border service SENAFRONT.[198] Also involved is the National Migration Service (Servicio Nacional de Migración, SNM).[199] Panama boasts of being the “only country in the region offering help and free humanitarian assistance” to migrants and asylum seekers.[200]

According to SNM, Panama invested over US$60 million in the strategy in 2022, including in expenses for migrant reception stations. The figure was expected to increase to $80 million in 2023.[201] Authorities say the state is “pushing the limits of its budgetary capacities.”[202]

The strategy also does little to protect the local, including Indigenous, communities from the unintended consequences of the increased numbers of people in their region, or to address chronic neglect and high levels of poverty in the Darién province.[203] According to the latest official statistics, income-based poverty rates in the Darién province (41.2 percent) were almost double national rates (21.8 percent). Monetary poverty is even higher in the Indigenous Emberá Wounaan “comarca,” territory under Indigenous jurisdiction recognized by Panamanian law, where it reaches 63.7 percent.[204] According to UNICEF, 6 out of 10 children in the Darién province, and 8 out of 10 in Comarcas, grow up in multidimensional poverty.[205]

Panamanian authorities appear to use the threat of criminal investigations for the crime of “smuggling” and SENAFRONT’s presence in some entry points by the border to influence migrants and asylum seekers to use certain routes, ensuring that others are not used, and that migrants and asylum seekers do not move freely around the country.[206]

Humanitarian Response

People regularly and urgently need social services upon arrival in Panama after walking for days through the jungle, including many children, older people, and people with disabilities or who are pregnant. Many arrive dehydrated, with sores, serious mosquito bites, and swollen ankles. Many have been assaulted by criminals during the trek, subjected to robbery and threats, and, in hundreds of cases between 2021 and 2023, sexual abuse. Some have not eaten or slept in days and require adequate food, water and clothing.

But Human Rights Watch found that Panamanian authorities make little effort to ensure the rights to food, water, and health care for people living in the Indigenous communities where migrants and asylum seekers first emerge from the Darién, for those people crossing through this region, and for those in the migrant reception stations. The insufficient support available for migrants and asylum seekers in this region in particular is mostly provided by UN agencies and humanitarian non-governmental organizations.

Indigenous Communities

The Indigenous communities of Bajo Chiquito and Canaán Membrillo, in the Emberá Wounaan comarca, serve as the migrants’ and asylum seekers’ first “shelter” after exiting the jungle. They are also, generally, where migrants and asylum seekers first encounter Panamanian authorities from SENAFRONT and the SNM. These Indigenous communities have played an important role in helping provide the goods and services necessary to ensure the rights of migrants and asylum seekers in this region, but these communities have also been largely neglected by Panamanian authorities, according to community members who spoke to Human Rights Watch.[207]

In both communities, people live in wooden houses on stilts, a traditional form of housing for Indigenous communities in the region, without adequate space for accommodating migrants and asylum seekers.[208] Rather, migrants and asylum seekers sleep in tents on the community’s playing fields or underneath houses, for which they pay the owners. Neither community has electricity, adequate water for drinking and sanitation, and sewage systems.[209]

Indigenous shops sell food, clothes, and shoes. Some locals allowed migrants and asylum seekers to receive money from abroad, charging fees as high as 20 percent. In February 2024, humanitarian organizations and the Ombudsperson’s Office reported that the money transfers ceased following the arrest of those responsible.[210]

Both communities are remote and hard to reach from other towns, on rutted roads or only by long river crossings during rainy season. It can take over four hours to reach Metetí by river and another three hours by car to the closest regional hospital. Lack of “social investment and infrastructure, institutional presence, and humanitarian aid” complicates their response to the hundreds of migrants and asylum seekers arriving daily, the Colombian and Panamanian Ombudsperson’s Offices and humanitarian groups have noted.[211]

The arrival of hundreds of migrants and asylum seekers each day is having a mixed impact on the Indigenous communities’ economy, culture, and access to services, according to local human rights institutions and humanitarian organizations. Eduardo Leblanc, who heads the Panamanian Ombudsperson’s Office, said that migration is providing significant economic income but contributing with the abandonment of traditional “culture, farming, and commercial activities” and pushing them to jobs related to the arrival and transit of migrants, such as transportation and providing food. It is also leading some Indigenous children to drop out of school.[212]

“We now live off the migrants,” the vice president of Canaán Membrillo told Human Rights Watch. The income allows people to buy food, improve their homes, and afford transportation and internet access, he said. “Before, it was very hard because there was no state [presence] in the area—or any help.”[213]

The Panamanian Ministry of the Environment has reported environmental impacts from the transit of migrants throughout the Darién and neighboring communities, including an increase in human waste or trash in the rivers.[214]

Bajo Chiquito

Bajo Chiquito, an Indigenous community of some 200 people, on the Turquesa River, where migrants and asylum seekers taking the routes from Acandí and Capurganá generally arrive.[215]

Bajo Chiquito inhabitants told Global Brigades, an international NGO, that two of their top needs were access to drinking water and adequate health care center.[216] Global Brigades estimated that only six percent of homes have latrines—leaving hundreds of people, locals as well as migrants, to use the river for their sanitation needs.[217]

Migrants and asylum seekers, according to Panamanian authorities, are supposed to stay in Bajo Chiquito only one night.[218] The next day, SENAFRONT and SNM officers organize and direct them to Indigenous community members who transport them by boat to Lajas Blancas, which has a migrant reception station.

But at times migrants and asylum seekers have to stay for more time, due to lack of sufficient boats or because they do not have money to pay for these. In March 2023, the number arriving far exceeded the number of people placed on the boats by Panamanian authorities to take them downriver. Some waited for as long as 15 days.[219] Some 6,500 people were stuck in Bajo Chiquito between March 1 and 10, 2023, UNICEF reported.[220]

According to Panamanian data, in 2023 an average of 1,500 people arrived daily, reaching peaks of 4,000 arrivals in August.[221]

|

Priscila Borja (pseudonym), 32, who came from Venezuela with her husband Pedro (pseudonym) and their 4-year-old daughter Paula (pseudonym), was among the 2,500 people stuck in Bajo Chiquito in March 2023.[222] Human Rights Watch interviewed Priscila five days after they arrived. She and Pedro had pitched their tent in a dirty area along the riverbank. “There are better places to sleep, but the owners of the houses charge money daily for you to set your tent there,” Priscila said. “Here, it is free.” She estimated they were spending US$10 to $12 a day to buy food and drinks. Paula, weakened by diarrhea, laid in Priscila’s arms, sleepy, and, in temperatures peaking at 37 degrees Celsius (100 degrees Fahrenheit), covered in sweat. The family had no diapers or sufficient clothes to change her. “She is dehydrated, but the doctor said he does not have enough medicine to give her,” Priscila said. “We just want to get out of here as soon as possible.” |

Few government agencies serve Bajo Chiquito. The National Service for Children, Adolescents and Families (Servicio Nacional de Niñez, Adolescencia y Familia, SENNIAF) and the National Office for Refugee Care (Oficina Nacional para la Atención de Refugiados, ONPAR) are not present. The only Panamanian agencies operating in the area are:

- In August 2022, the Ministry of Health stationed a doctor, a nurse, and a nursing technician in Bajo Chiquito.[223] The doctor who was there in March 2023 told Human Rights Watch that they had not received medications since December 2022. At the time, there were no drugs to reduce fever and relieve pain, such as acetaminophen, paracetamol, and diclofenac. “We do not have medicine or medical equipment to respond to miscarriages, severe dehydration, or people vomiting blood,” a nursing technician said. The doctor said they were examining around 250 patients daily.[224]

- Medicine shortages continue as of writing.[225]

Between June 2023 and early March 2024, the Ministry of Health doctors worked in coordination with MSF.[226] On March 4, Panamanian authorities forced MSF to suspend their work in the Darién Gap.[227]

- Since June 2023, a prosecutor has taken in criminal complaints for abuses that occurred in the Gap. Only male prosecutors are deployed to Bajo Chiquito.[228]

- SENAFRONT reported eight male officers deployed to Bajo Chiquito, in April 2023, on 30-day shifts.[229] The 2008 decree that established SENAFRONT mandated that the officers should “preserve public order,” and “prevent, respond to, and investigate” crimes at Panamanian borders.[230] When Human Rights Watch visited in March 2023, there was a single female officer who said she was in charge of helping unaccompanied children.[231]

- SNM maintains several officers in Bajo Chiquito to register entering migrants and refugees.[232] They gather data on the number, nationality, age, and gender of the people arriving.[233]

|